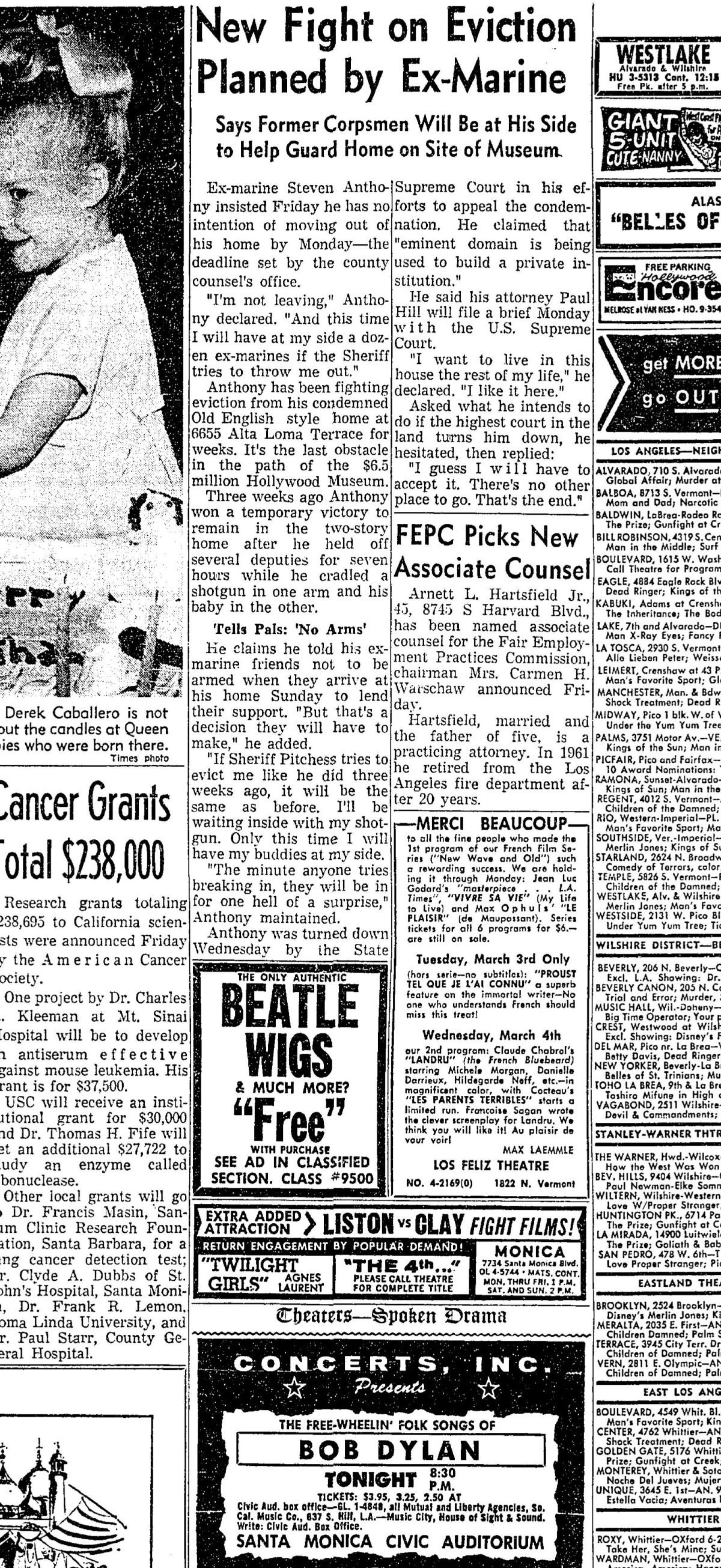

Some remarkable photographs from 1964 show openly Republican women, out and proud, at Sportsman’s Lodge in Studio City. They had gathered to support the candidacy of George Murphy for the US Senate. Dressed in flowered hats, mink stoles and gloves, the ladies, as they were referred to back then, held a luncheon in the heart of the now 100% liberal district.

Mr. Murphy won the election and served from 1965-71.

A Wikipedia entry describes a Reaganesque sounding entertainer:

“George Lloyd Murphy (July 4, 1902 – May 3, 1992) was an American dancer, actor, and politician. Murphy was a song-and-dance leading man in many big-budget Hollywood musicals from 1930 to 1952. He was the president of the Screen Actors Guild from 1944 to 1946, and was awarded an honorary Academy Award in 1951. Murphy served from 1965 to 1971 as U.S. Senator from California, the first notable U.S. actor to make the successful transition to elected official in California, predating Ronald Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger.[1] He is the only United States Senator represented by a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.”

At the time, marijuana and homosexuality were illegal, a woman needed her husband’s permission for a bank loan, a drunk sleeping on the street would be arrested, almost nobody was obese, tattoos were for sailors and people in the circus, and the Republican Party was the sworn enemy of Russia. Children walked to school and rode bikes, and most adults smoked at home, in the office, in movie theaters, and while driving in their cars.

How most Californians survived growing up with free tuition, plentiful jobs and cheap housing is beyond our imagination. We are fortunate to be living in a much more progressive and kinder era with homeless encampments and marijuana dispensaries in every neighborhood.

Courtesy of the Valey Times and the LAPL:

Photograph article dated January 28, 1964 reads, “At the kick-off of 1964 campaign activities of the Laurel Oaks Republican Women’s Club, more than 300 political leaders and Valley Republican women gathered to hear George Murphy, candidate for the United States Senate. Mrs. Edward Gephart was general chairman of the tea, which was held at Sportsmen’s Lodge, Studio City. Honored guests were California leaders of the Republican Women and Valley government officials. John Willis, television and radio newscaster, was master of ceremonies.” Mrs. Ben Reddick, wife of Valley Times publisher, serves tea to Mrs. Allen K. Wood, Sherman Oaks. Mrs. Wood also poured at the tea table.

You must be logged in to post a comment.