Cole Taro, a successful, retired, casually Jewish, Hollywood producer returns to live in his hometown and finds everything progressive, yet one evil remains unchanged.

Middleview, Illinois is in the middle between Chicago and Milwaukee, 45 miles in either direction. I grew up there. I left 40 years ago. I returned with my husband to find a place to live. My name is Cole Taro. This is a story of return.

Realtor Jackie Wabash drove us around in her Mercedes SUV. Philippe was in the passenger seat. I was in back staring out the window at frames of my life.

She was about 40, overdressed, as only women in Chicagoland and Paris are.

She wore a black and white houndstooth coat over black leather pants, gold and diamond bracelet, black boots and black leather driving gloves. Her well-coiffed hair glistened, her lips were red and glossy, her eyelashes were prominent, her perfume was Chanel Bois Des Iles.

I screened out their banter as we drove past the 1930s fire station, post office, and municipal building, all erected by the WPA in modified Art Deco.

I saw the former home of Bank of Middleview, built in 1966, black brick and golden flagstone, modernistic arches and tall glass windows. My mother used to cash $10 checks at the drive-through. It was now Walgreens and they still had a drive-through, but there they now dispensed prescriptions.

Philippe was an architect but never quite supported himself. I was way better off, having produced television for nearly 40 years. We had sold our home in Los Angeles and planned to travel around Europe, possibly staying with his widowed father in Bayeux, Normandy, France.

But then Philippe got work. He made a contact through The Classical Foundation and was hired by a wealthy socialite to rebuild a French Chateau in Lake Forest next to Lake Michigan.

On the day he got the offer he came out to talk to me as I sat by our pool in the backyard, perusing Variety, embittered with every project that I was not a part of.

“Would you consider moving to the Chicago area? I just got a big job offer. The money is good. This would be a step up for me to design a large home,” he said.

“Is it absolutely necessary?” I asked.

“I think so. Unless you think your retirement is more important,” he said.

“We have this battle all the time. I don’t think less of architecture compared to show running. I haven’t complained too much,” I said.

“You are complaining by bringing it up. Why can’t you respect my work?” he asked.

“Work? Philippe you’ve had one commission in the last ten years. Rebuilding Christa Miller’s pool cabana in Malibu,” I said.

“You never lifted a finger to promote me, to let your celebrity friends know about me. When I was young and handsome that was my sole purpose in your life. A male model on your arm,” he said.

In truth I practiced discretion. I was quiet and real and did not use my associations for his benefit. But he had a point. He was once breathtaking. Maybe I did employ him for that purpose.

He had moved to California in the belief that the right connections, good looks and good luck would secure him. He was practicing architecture the way people practice networking in Hollywood and it never quite worked out for him.

And I was just too old.

Maybe we both belonged back in Illinois.

After 60, I was no longer employable in Hollywood. There were residual checks, the 401K, the profit we made selling the house, but my future was behind me. All the skills I mastered, after working 35 years in television production, were obsolete once my gray hair took over.

My self-esteem had been working. Without it I deflated like a balloon.

I returned to four seasons, dramatic weather, nasal accents and flat vistas that always terminated in memories. And to people who stared in admiration, curiosity or contempt when you walked into a restaurant and locked their eyes on you, a custom of the region.

“Is Swanson’s Bakery still on Central?” I asked as we rode down Maple, a lush block of homely ranches, sturdy bungalows and chaste colonials embedded with golden October leaves.

“That’s Thai Kingdom now. We also have Vietnamese, Indian, Chinese, Mexican, Burmese. It’s very diverse. And we love it,” she said, in the cheery way all realtors talk, where everything is a plus.

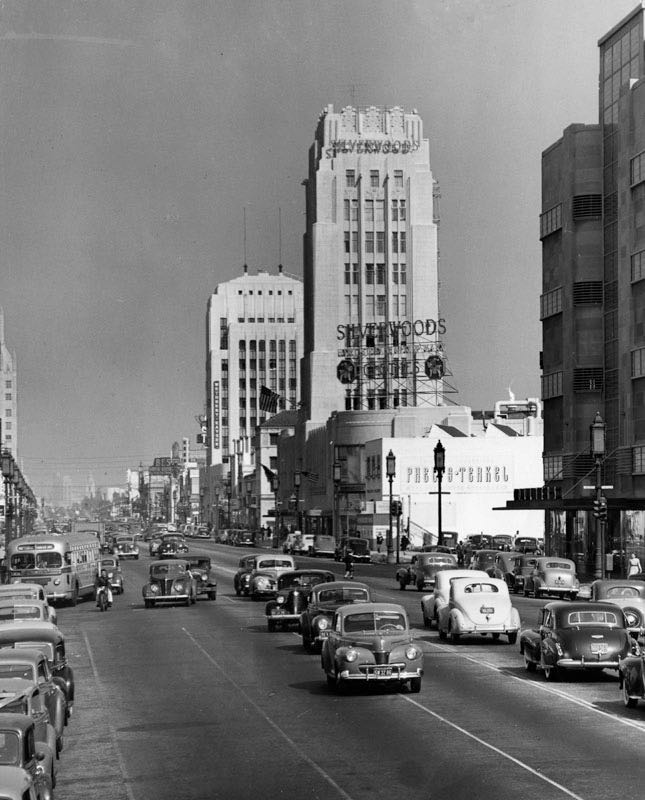

On Central, the main drag, we passed one-and two-story brick buildings with their owners’ names inscribed high up on pediments: Krause Block 1924, Heinrich Block 1910, Keller Block 1915. Red brick, yellow brick; plate glass windows, awnings, transom windows and barber poles. Solid, respectable, old time German American.

We drove past the three storefronts that replaced Konig Drugs. Now it was subdivided into Starbucks, T-Mobile, and a boba tea store.

“The village added decorative lampposts, benches, cobblestones, and trees along the whole stretch and it has really improved the town. See all the gay flags out front too,” she said, adding the last feature for our benefit.

She turned right on Catalpa Avenue passing Strom Place, a five-story tall senior apartment building with ramps and guardrails. It replaced Strom Brothers Nursery, once owned by a horse toothed Swiss family who always made a big Christmas presentation every year, with decorated trees along the street, bowls of Hershey chocolate kisses, a mechanical, waving Santa Claus, reindeer and a soundtrack of amplified holiday songs.

On Dartmouth Avenue, south of the business district, we drove by old Victorians with turrets and front porches, now dentists and doctors’ offices. They had the look of life after death, places you went to get your teeth cleaned or your colon wiped.

“This area near the tracks used to be considered less desirable, but now it’s walkable, near the train, shops and highly in demand by young families. I know you fellas are looking for rentals. But let me take you to 868 Hackberry, a house for sale. I think you will love it, especially Philippe because you’re an architect and Cole is a photographer,” she said.

“He’s an executive producer! He worked on Friends, produced Malcolm in the Middle and The Simpsons!” Philippe corrected.

“The Simpsons! Friends! Oh, my goodness. Your parents must be proud,” she said.

“They were before they died,” I said.

She drove down Locust, yet another picturesque and quaint block of old houses with young residents, solar panels, electric vehicles and yard signs of tolerance.

Where Locust bisected Hackberry stood 868, a white, two story tall, center hall colonial with black shutters and pergola roofed porches at both ends, enclosed in glass panes. We parked in front.

The house was in bad condition: peeling paint, cracked sidewalk, missing roof tiles, rotted wood shutters.

“It’s been on the market for over a year. Two bathrooms, four bedrooms. Kitchen dates back to the 1940s. Electrical, plumbing, roof, everything needs replacing. This was designed in 1918 by a noted classical architect, Robert Seyfarth,” Jackie said.

“A classicist? Perfect. We will get along. I design exclusively in that realm,” Philippe said, in a manner only he could summon, haughty and Gallic. I thought of Christa Miller’s modernist pool cabana in Malibu, a glass and steel box, and wondered if that disqualified him.

He got out of the car walking with reverence and awe along the sidewalk facing the house. “Yes, this is a special home. The proportions are excellent,” he said, adjusting his long neck scarf.

Jackie and I followed him. I imagined living here on Hackberry Avenue, walking under the trees, waving to the neighbors, hanging out at the coffee shop, possibly meeting new and young.

“How much would this cost in LA?” Jackie asked, her inquiry meant to solicit a comparison showcasing a real Chicagoland bargain.

“Well depends where in LA. In our old neighborhood in Brentwood, I’d guess maybe three million,” I said.

“This four-bedroom home is only $320,000. Granted it needs $200,000 work, at least, but think about it. You could have a really charming, historic house in the hottest town north of Chicago for peanuts. There’s Whole Foods and CVS three blocks from here. And the town is very diverse but very safe,” she said.

Frank and Janet would have been shocked at the multi-faceted ethnicity of modern Middleview. In my parents’ time it was all white, and we Jews were the outliers. Perhaps 1,000 of us in a town of 15,000 descendants of German, Swedish and Irish farm families.

“Do you know Temple Sholom? Is it still on Highway 46?” I asked.

“Hmmm. I don’t know for sure. I think the congregation left the building and moved to Lost Hills. I can ask a Jewish friend who might know. Why?” she asked.

“My family used to go there. It was a small synagogue, with modern architecture, in the woods, along the train tracks. I figured they sold it off, developed it,” I said.

“Come to think of it I do know it. That’s the property the town has been battling over. Middleview wanted to put affordable housing there, but the owners didn’t want to sell, holding out for luxury homes. A lot of the people who went to that temple are lawyers so it’s tied up in litigation. When you were a kid, I heard Middleview was like 90% Jewish,” she said.

“No. Not at all. Hardly,” I said, laughing off her ignorance.

In any estimation of Jews, it’s either 90% or 1%.

We bought 868 Hackberry with the mutual proviso that our stop here was temporary; a lark, a project, a two-year long production with a crew and cast of contractors, electricians, roofers, painters, and landscapers. When it was done, when Philippe’s work was completed, we would sell and get out for good.

But the house renovation was also a metaphor for our relationship.

I did the work, Philippe was absent, strangely uninterested in our domestic architectural project. His focus was his $15 million-dollar French Chateau project in Lake Forest.

We had a division of labor, separate projects to keep us separate as a way to keep us together.

His daily departure was a breather for me, and I went full anti-LA, walking everywhere in town. I also tended to the domestic duties at home: grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning, and finding trades people to paint, wire, plumb, roof, tile, and refinish floors.

When I spoke to people back in LA I bragged about my small-town life, sugar coating it to sound ideal, the way Angelenos torture middle western people with sun and citrus filled stories in the dead of winter. “We leave our doors unlocked, nobody is homeless, there isn’t any illegal dumping.”

But I was truly back in Middleview, IL.

There were no celebrities, no Santa Monica, no Palm Springs, no Tournament of Roses, no dinners with Executive Producer Bill Lawrence and his wife actress Christa Miller.

I thought about growing up here, gay; the laughing taunts when I wore a pink shirt or purple velour, when I admitted playing with Barbie dolls, when I dropped a ball in left field daydreaming about Bewitched, when I was chosen last for teams by jocks loudly protesting: “I don’t want that faggot.”

If those bullies could only see me now, making design boards on Pinterest, testing paint samples, picking out wallpaper, planting herbs in the backyard, baking sourdough.

Dr. Dewey

“They don’t grade anymore. The school has system of evaluating students that considers many factors. My son Tommy is one of 12 Black kids graduating from high school and entering an Ivy League college.”

I met Dr. Liz Dewey, early 40s, at Middleview Hospital when I went in for a check-up. Despite my running, weightlifting and spa diets I had high cholesterol and pre-diabetes. She prescribed statins.

She said she was divorced and raising three teen sons alone. They rented an apartment in town, two bedrooms above Starbucks. Even on her doctor’s income she couldn’t afford to buy a house.

“I’m not done paying off $300,000 in medical school loans. I have three boys who are two years apart, and Tommy is going to college next year. God willing they’ll all get scholarships. I don’t take a dime from my ex-husband Rod. I wish I could buy a little home here in town but the dream is taking longer than expected,” she said.

“What part of town would you like to live in?” I asked.

“Any part! Ten years ago, they were going to build a little development on the site of Temple Sholom. The plans were lovely with a small park and pretty houses and it would have been in my budget. But now it’s all tied up in litigation,” she said.

“I can feel your pain,” I said.

“What kind of name is Taro? Is that Filipino?” she asked.

“No. Actually it is shortened from Tarofsky. Russian Jewish,” I answered.

“I wouldn’t have guessed,” she said.

The Bike Ride

Philippe went to his job site most weekdays. He came home for dinner, which I always had waiting. We ate in silence. He drank two glasses of wine and fell asleep on the sofa at 8pm. I often left him down there, overnight.

I bought a clunky tire bike, imitating childhood, riding alone and exploring.

One sunny and cool October day I took a jaunt up to the old grounds of Temple Sholom to see what had become of it.

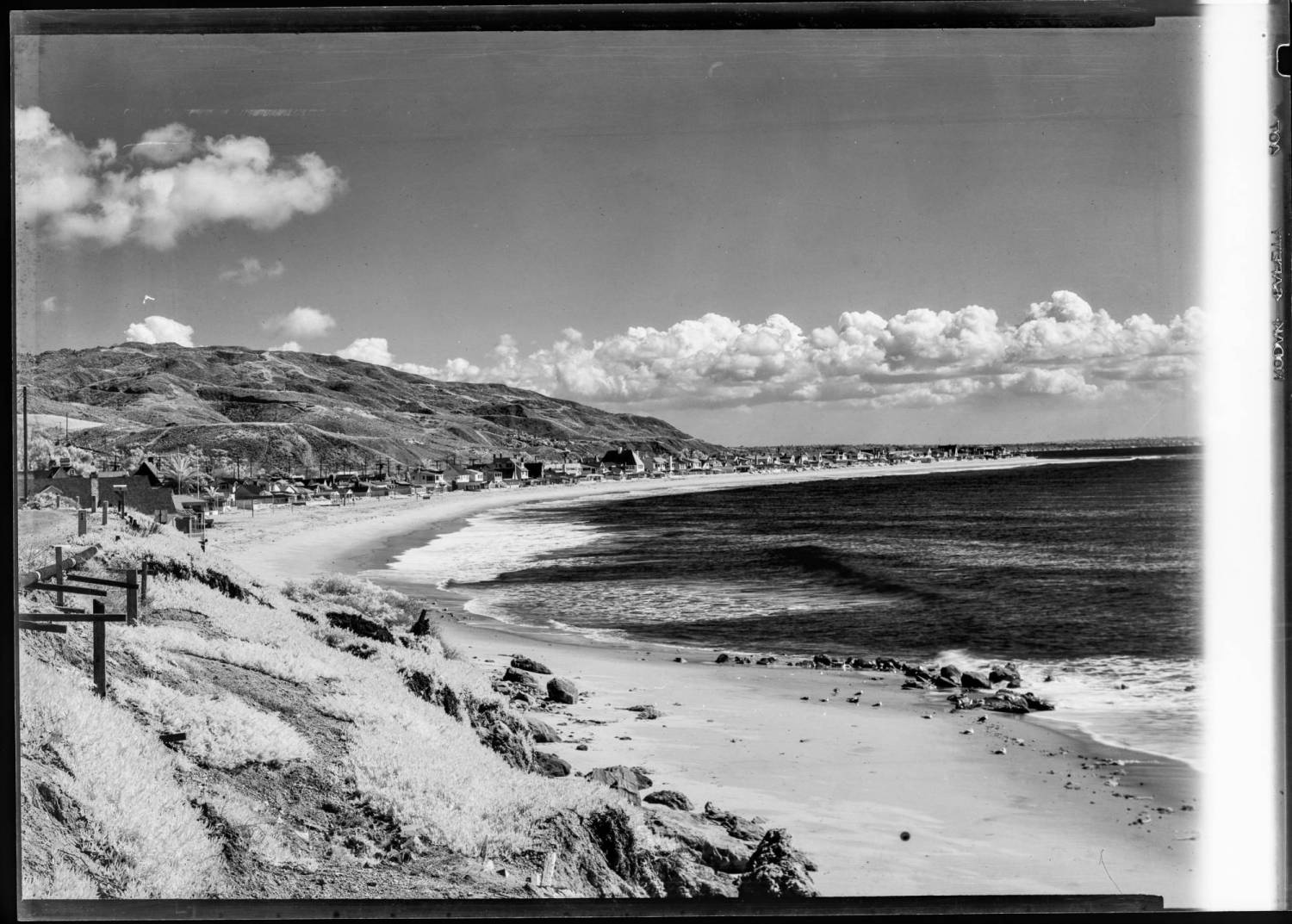

I rode on the new bike trail built over the dismantled Chicago & Northwestern freight train tracks alongside Highway 46, north of town.

I didn’t see another soul. It felt wild and rural, with the tall grasses and the line-up of the high voltage towers and transmission lines marching north to Wisconsin. I saw a red-tailed hawk in the sky and passed deer in the woods.

I spotted the abandoned synagogue through the trees. I dismounted and walked my bike off the trail, down a rock and gravel slope, guiding the handlebars, pushing the wheels into nature, into high, feathered grasses, monarch butterflies, dried leaves and rotting tree limbs.

And then I entered the temple property, a shaded oasis of fir, oak, hickory and maple. The air was fetid and humid. Little birds in the trees flew down to bathe in the puddles. A frog croaked.

A hexagonal wood bench encircled a thick trunked Kentucky Coffee Bean tree. I laid my bike on the ground and sat down and saw Temple Sholom for the first time as I had never seen it before.

An asphalt driveway looped under a glass and concrete building with a cantilevered, angled roof supported by two V-shaped steel posts, 20 feet tall, an arrow pointed, jet-age composition shooting upward into the western sky, aiming into the American frontier, the American future, the way west I once went.

Here on that automotive entrance to the synagogue, the Cadillacs, the Buicks, the Oldsmobiles, the Pontiacs and the Chevrolets (never the Fords) dropped off the women in furs, veiled hats, pearls, and high heels, and Marshall Fields dressed boys and girls.

The war veteran husbands parked their cars in the lot and walked ruggedly in the rain and snow to join their family for worship inside the progressive and safe congregation, slipping on yarmulkes from the box just inside the chapel doors, their freshly shaved faces and Jewish head toppings as unlikely a pairing as a bacon sandwich with matzo ball soup.

Ah, the days when American Jews went to temple without armed security guards.

Summoning the past, I felt God as I sat there. Were the ghosts of my parents and grandparents with me reciting the Kaddish Prayer?

What had become of the Hebrew School and the sanctuary and the ark where they kept the Torah? What became of those living, laughing and procreating souls who worshipped here with their families?

Then I thought of how I really felt about my time at Temple Sholom, the last time I was here.

How I hated Hebrew school! How I wanted to be free of learning the haftorah for my Bar Mitzvah! How boring the sermons! The somnambulating prayers! The invocations! The rituals.

The Lord is our God! The Lord is One!

Ein Keloheinu. Ein keloheinu, ein kadoneinu, ein kemalkeinu, ein kemosheinu.

How I secretly crushed on Avi Naron, a green-eyed Israeli with long brown hair, brown beard and broad shoulders who served in the army and came to teach Hebrew. That summer of ’74 I suddenly cared about continuing my religious instruction. Then Avi went back to Israel and I dropped out of the temple.

A few years later I graduated Middleview High School and went to Harvard, and to Hollywood, to capture the same secret dream everyone else on Earth wants.

All of it came back as I sat in the woods next to the empty former home of Temple Sholom.

I had been granted all my wishes in life. But on that day, I wished I could fly back in time, and assume the world I once lived in, young, naïve, and hopeful.

Meeting Tommy

One day I was in Starbucks, waiting for my coffee, and I bumped into Dr. Dewey and her son Tommy.

She introduced me by name and profession.

“Tommy, this is Cole Taro, the Hollywood producer who just settled back in town. You two will have a lot in common,” she said.

“Nice to meet you sir,” he said.

He was six feet tall, green eyed, dark skinned, dressed in a blue oxford shirt and khakis, enviably trim, athletic, young and 17. His afro was close cropped, he carried himself adroitly, poured cream into his mother’s coffee, kissed her good-bye, and politely ushered me to a bench as if I were an elderly relative.

Dr. Dewey left the store, and Tommy stayed there and sat down at a table next to me. I asked him about school.

“This is my homework today. Writing an essay for 20th Century History. I picked the 1930s, it’s due tomorrow. Shit! Sorry about that. I forgot my book upstairs. Can you watch my laptop? I’ll be back in a minute,” he said, running outside and up the stairs to his apartment.

I peeked over to his notebook and read some of his handwritten notes about Kristallnacht, the German riot of November 10, 1938, where thousands of Jews were assaulted, murdered, rounded up and sent to concentration camps; synagogues set ablaze, shop windows broken, businesses ransacked; violence inflicted on innocent people for national amusement.

He came back fast, sliding into his seat, laughing.

“I’m so dumb at times. How do you write a history paper without a history textbook?” he asked.

“Google?” I asked.

“No. I like to challenge myself. I don’t cheat. The teacher knows if you haven’t studied. Mom said you were a Hollywood producer. That’s a goal of mine. I want to go to Harvard and work in film or TV. Acting, modeling, directing, producing,” he said, confident that his multiple careers would surely succeed.

“I went to Harvard. Never modeled, as you can guess, too short. But just like you I grew up in Middleview. I wonder if we’re related,” I joked.

“I wish. I’d rather have you for a father,” he said.

Was his father in prison? Did he abandon his family? It seemed.

“Do you see your dad?” I asked, fishing for jail tales.

“I don’t want to talk about him. Too tragic. Tell me how you got famous in Hollywood,” he said.

I wanted to tell him to run fast from show business, to avoid Hollywood at all costs, California and celebrity, the whole farce and scam.

But then I looked into his innocent face, a child’s face, asking me to bestow my elderly wisdom and guide him.

“Any questions you have, let me know and I can meet you here. We can talk and I’ll be more than happy to help,” I said, also assuring that any meeting with this beautiful, inquisitive minor would take place in a public setting.

Unspoken Encounter

Janet used to say the weather was all downhill after Halloween. November was the beginning of five months of cold, dreariness, sleet, snow, and long wind chilled nights.

But on Thursday, November 10th it was 65 degrees, warm, sunny and mild.

I went out on the bike trail again. I wore a rust color Shetland sweater, brown corduroy pants and hiking boots.

The bike path was empty. The air smelled of bergamot and milkweed, and every so often a gorgeous bird would fly past: Dickcissels, Bobolinks, Meadowlarks, Sparrows and Blackbirds.

I rode in leisure, unhurried, mesmerized, tall clouds floating by. There were no cars, no planes, just me and nature.

I stopped where Middleview ended at Lost Hills Road.

Then I turned around and rode back. I thought of lunch, my mother’s toasted cheese sandwiches and condensed tomato soup with milk.

Near Temple Sholom, I spotted Tommy Dewey in the distance, oblivious to me, pushing his bicycle up onto the trail. He mounted his bike and carried a red gasoline can in his left hand, steering with his right hand, pedaling slowly.

And then he hurled the can into the tall grass, grabbed the bike handlebars with two hands, stood up and sped out of sight.

Only later did I have any significance attached to that strange sighting of Tommy.

“An unknown arsonist has set fire to the abandoned building that once housed Temple Sholom in Middleview. A rabbi spoke about the pain of this happening on the 84th anniversary of Kristallnacht. The building was damaged, fire personnel extinguished it in 30 minutes. Nobody was injured but the symbolism of the crime could not be denied. Perhaps it was the work of white nationalists?” -WLS-TV News

I kept silent and told nobody about the suspected arsonist. I was sorrowful and heartbroken. Yet still I had empathy and affection for Tommy Dewey.

Gochujang Feast

On Thanksgiving we had potluck party with a few new friends.

This included Tim Park and Lucinda Nguyen. He owned Old Seoul Korean restaurant and she was a city planner in Evanston. We also invited architect Vijay Patel and his boyfriend, attorney Howard Chan. Dr. Dewey came after work, alone, her boys were spending the holiday with their grandmother in Blue Island.

We showed off our renovations: the matte finish oak floors, the creamy walls, the white Zellige tiled bathrooms, the kitchen with the Wedgewood stove and the black and white tile floor, the living room furnished with $20,000 of Sixpenny linen and down sectional seating and round travertine coffee table.

Everything was ordered online with a click and a credit card. All it took was money and mouse pointing. But it looked good and they were full of compliments. The house was exquisite, the furnishings were splendid, nobody knew of our troubles because our surfaces gleamed.

“I’m very envious of your home. Do I sound like a jealous person?” Dr. Dewey asked.

“Thank you, Liz. I’m confident you are going to have just as nice a place very soon,” I said.

“I have to get the three monsters off to college, buy a house and then you two are going to have to come over and decorate it. Can we shake on it?” she said.

We had a buffet and the guests loaded up their plates with gochujang marinated eggplants, spicy Pork Bulgogi, Taiwanese Egg Tarts, Indian vegetable samosas and corn fritters with mango chutney, and Red Vietnamese Fried Rice. We drank soju and craft beer and sat informally in the living room, plates on laps.

We talked about Middleview, the temple fire, and who might have done it.

“I think they set their own temple on fire to collect insurance. That was the MO for the South Bronx in the 1970s. The landlords know they get a better pay out then selling. Jewish lightning, excuse my language,” Dr. Dewey said.

Lucinda didn’t agree. “Oh Liz. That’s not nice. Even though it’s true! Why would the congregation commit arson for financial gain? Very risky and criminal,” she said.

“Look at Trump. You think crime doesn’t pay?” Dr. Dewey asked.

Philippe, standing, blue eyes on me, condemned antisemitism and the Holocaust, and then he took a swipe at an even greater evil: bad land development.

“Europe was destroyed by WWII but America destroyed its cities and countryside with sprawl, banker greed and urban renewal. Why not preserve the open spaces and make the cities better?” he argued.

“It should be a park, or a nature preserve, or affordable housing. But obviously the owners are greedy and want to sell to the highest bidder,” Lucinda said.

“Look at all of us. We are the melting pot future of Middleview. This is a tolerant town,” Tim Park said.

Vijay agreed and praised the diversity of Middleview. He said he felt completely at home in the town and couldn’t imagine any kind of open hatred of any minority group here. “Mumbai speaks more prejudice in one day than you will hear in ten years in Middleview. Especially against Muslims,” he said.

Tim Park told a story about staying open on Christmas Eve last year and having to serve demanding Jewish customers who didn’t seem to appreciate that this was a holiday where he was short staffed. “They are that way, aren’t they?” Lucinda said.

“Demanding and aggressive. But that’s how you succeed in life. Look at Trump,” Dr. Dewey said.

“The whole GOP. White Christian bigots,” Howard Chan added.

They gabbed, spinning a roulette wheel of insults, drinks, smiles and slurs, oblivious to their words, unaware of this closeted Jew in their presence.

And I felt alienation amongst these highly educated, affluent, open-minded, non-white, diverse people feasting on the eternal king of kings of hatreds.

Reunion

On the corner of Hackberry and Frontage stood an old golden brick bungalow, in prime condition, with five leaded, stained-glass windows in a polygonal bay. The roof was green tile. A concrete walk and six concrete steps lead up to an enclosed, arched porchway. A small crew cut lawn and a flower bed of geraniums under the living room windows completed a picture of orderliness and pride.

I stood in front and observed it. It must have been the original house in the neighborhood, perhaps a farmhouse on the prairie.

It was December 9th and that was Janet’s birthday, a date she dreaded and never let us forget. She expected to die every year, even when she was young and in good health, and her favorite admonition to me was, “I hope you’ll remember what your mother did for you when she was alive.”

She was an avid reader, theater goer, and cigarette smoker, a mid-twentieth century, cultured urbanite exiled on the outer range of suburbia. Her husband had no cultural interests, only watching the Cubs and the Bears on TV. They were completely unsuited and incompatible.

“Your father has a tire store. I once dreamed I’d marry a doctor or lawyer but I married Firestone, so I guess that counts for something,” she said.

Her themes were rage, disappointment, anger, resentment, self-pity and vodka. She fought hard with sarcasm and guilt, eventually dying of Alzheimers fifteen years ago.

I was living in Los Angeles and had to fly back to Boca Raton. She was cremated. We held a small memorial service at the retirement home where a rabbi they never met spoke about her life, how there was a time to live and a time to die.

A few months later Dad died. Another cremation, another memorial attended by their neighbors in Florida, another rabbinical speech with glued together words signifying nothing personal about my father but professing to know quite well the will of the invisible God.

Everything that had encased me in their moroseness was lifted, a relief.

But December 9th remained in my mind as a dark day on the calendar.

I thought of her as I stood in front of the neat bungalow which was once the home of my 6th grade math teacher, Miss Anna Frisch, a strict lady who demanded fealty to numbers, formulas and equations. She lived here with her father, an old man who founded Middleview, or so we were told. Miss Frisch also sewed and did alterations; my mother came here for tailoring.

“Her house is so neat and tidy. She is a very capable woman, hardworking, very reasonable. It’s strange she never married,” Janet said.

I was alone, in my thoughts, when I heard tapping on a glass window. I saw a white-haired woman behind a lace curtain knocking and pointing at me. Had I done something wrong?

The front door opened and the old woman, dressed in her bathrobe, came out and stood on her porch. “What are you looking at? Who are you?” she demanded, in that accusing voice, in that eternal Midwestern tradition of property patrol.

“I’m sorry. My schoolteacher once lived here many years ago. I was her student,” I said.

“Come here! I can’t hear you. Did you say teacher?” she asked.

I smiled and walked like a shamed boy to look up at her high up six steps.

“I am a teacher. Miss Anna Frisch. Who are you?” she asked.

“Oh dear. I didn’t know you were still alive! I’m terribly sorry. My name is Cole Taro,” I blurted.

“Yes, still alive! What an unpleasant shock for you. My apologies. I’m 96! I’ve been here all my life. I don’t remember you. What year did I teach you?” she asked.

“1975-76. You might remember me because me and my friends terrorized you in front of this very house one day on bicycles. I had to apologize to you for yelling Heil,” I said.

“Kids did that every year. Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler! They tortured my father. They had no shame. You were nothing special. Why don’t you come in for a beer?” she asked, laughing.

I went into the house and we sat in the sunny parlor on the plastic protected yellow sofa. There was an upright piano, Singer sewing machine and 1940s walnut Zenith radio cabinet. A vase of dried Eucalyptus perfumed the rooms. A glass bowl with water sat atop a lace covered radiator.

“Sit down here. I’ll be right back,” she ordered.

A 1940s Martha Tilton record played.

“The Last Time I Saw You”

Was the last time I saw you, the last time?

Or can I hope to hold you once more?

What about me, could have made you doubt me?

Want to live without me?

Loving me no more?

She brought out two cold bottles of Michelob. She walked briskly, vigorously, determinedly.

“How do you stay so fit?” I asked.

“I sweep the walk, I walk to market, I dust the floor, I scrub the bathroom, I clean windows, I even chop ice on the steps. My father lived until 99 and he did the same! A beer a day helps too,” she said.

She sat down and told me the story of her father Karl.

He was born in 1895. He lived for 15 miserable years in St. Walburg Orphanage in Eichstätt, Bavaria. His Uncle Walter and Aunt Julia had three grown sons and a 100-acre farm in Middleview. They brought 16-year-old Karl here in 1911.

His three male cousins resented the fourth boy from Germany as a threat to their inheritance. They abused him and gave him the dirtiest jobs: cleaning the barn and the outhouse, digging wells, milking the cows and getting up in the middle of the night to start his day.

In 1918, his uncle built this bungalow as a gift for his eldest son and daughter-in-law. The two unmarried sons also moved into this house. There were six adults living here.

Karl was left in the old cabin out in the fields. And he worked there six days a week sunup to sundown.

On Thanksgiving Day 1918 they invited him for dinner.

He came dressed in his only wool suit and silk tie.

But instead of the family and feast he found a masked priest and doctor. Everyone here had died of influenza. Husband, wife, three sons, daughter-in-law. All in one day.

“Die Sonne kam heraus. Ich war frei. The sun came out. I was free,” Anna said, quoting her father.

“He inherited 100 acres of land, $80,000 life insurance, $10,000 from the old man’s savings. And this new bungalow. Papa got everything. Money and land,” she said.

In the early 1920s, Karl and his new wife Bertha, Anna’s mother, partnered with a builder to develop this neighborhood of Middleview, laying out streets, and subdividing it into lots. Some of the homes were bought for $3,000-$5,000 from kits sold by Sears which shipped all the building materials by train.

Anna was the only surviving child. Three older sisters died before Anna was born in 1927. This sunny, sparkling, happy bungalow hosted many funerals.

Anna grew up privileged, with a position as the only surviving child, the daughter of the richest man in town, and a member of a family whose name was synonymous with heritage.

I asked her what she thought about modern Middleview. She said she liked it. She said the changes were an improvement, and she got along with everyone.

“I keep quiet. I stay out of other people’s business. I don’t like controversy,” she said.

I told her I was gay. I thought that might evoke her revulsion. “When you have somebody who loves you that’s all that matters,” she said.

I went to another topic to test her tolerance.

“What about the Temple Sholom property? Do you think they are doing it for profit?” I asked.

“Who is doing what? Who are they?” she asked.

“The town wanted to develop it for modestly priced housing. And the synagogue owns the property. I heard they are looking to develop luxury homes,” I said.

“You don’t know what you are talking about. They don’t own it. The Jews don’t own the land or the temple,” she said.

“Are you saying it’s a conspiracy?” I asked, fearing the worst.

“I own it! It was never the Jews! It’s wetlands, a swamp. The Benedictine sisters wanted it for a school and convent in the 1940s. But my father hated the Catholics. He wouldn’t sell it to them. He remembered the mean nuns and the sadistic priests. He met a German Jew, Rabbi Einstein. They got along well, those two old men. In 1951, he leased the land to the Jews for 50 years. That land was never sold. They built their prayer house but they paid us rent! I decide what goes on that property! And it’s a natural habitat, a place for rainwater, trees, birds, frogs, deer, snakes and not a place to turn into another suburban tract!” she said.

“Why do people think the Jews own it and are holding out to make a killing?” I asked.

“You already know the answer to the question you’re asking,” she said.

Her sharp mind seemed undiminished by age.

“When I die, I have deeded it to the town for a wild preserve. They can name it after me if they wish, but while I’m alive I don’t want any fame or honor. It belongs to nature for all time,” she said.

“And the temple building?” I asked.

“Let them make it into an education center for children. They need to get outside, off their digital devices, go into the woods and experience nature! This is divine providence,” she said.

The Visitor

In January, a few days in, Philippe flew back to Bayeux, Normandy, France to look after his father. He planned to stay for a month. He had talked of working remotely, sourcing materials in France for his Lake Forest project. He took an Uber from his job site in Lake Forest to O’Hare Airport without saying good-bye.

I was alone in the house now, in the coldest, darkest, most desolate month.

A series of heavy storms came, dumping a few feet of snow, followed by many days of below freezing temperatures. I would look outside and see a squirrel climb a tree, scurry across a branch. After decades in LA, the novelty of northern winter was intriguing.

I went from room to room in the house, dusting, vacuuming, rearranging books by size and realizing I had no work, no partner, no project, nothing. I thought of our home in LA, the lemon and orange trees and the roses that bloomed in winter.

What insanity had gripped me to leave that and move here?

I lit a gardenia scented candle. And then I fell asleep on the sofa, under a mohair throw.

Early evening, I was awakened by a knock on the front door. I got up to answer.

It was Tommy, in black puffer jacket and white knit cap, backpack draped over his shoulders. He stood at the glass door smiling. In the back, Locust Avenue and its electric streetlamps stretched into the distance like an art lesson in vanishing points. I opened the door.

“Hey, what are you doing? Come in,” I said.

“Should I take off my shoes?” he said, shivering, snowflakes on jacket.

“Yes, please if you don’t mind. What brings you here?” I asked, ushering the boy in the pink brushed wool crew neck sweater and white jeans to a seat on the down filled sofa.

“Can I get you something to drink?” I asked.

He sat down on the sofa, sinking into relaxation.

“Water please. You are so kind!” he shouted to me in the kitchen.

I brought him a glass, placed it on the table. He was sniffing his sleeve.

“Coffee smell. Damn Starbucks downstairs,” he said.

“What brings you here?” I asked.

“My brothers are fighting again. It drives me crazy. I have to be the disciplinarian but they don’t respect me. Mom gets home at 10. I make them dinner which they don’t eat,” he said.

His legs were propped up on the coffee table, he laced his hands behind his head, he smiled.

“How is your mom?” I asked.

“Good. Working hard. Long hours, short tempers, worrying about us. She adores you,” he said.

“Oh, that’s nice,” I said.

“No really, she is crazy about you. Thinks you are the smartest, talented, most successful man. She looked you up on IMDB, all your credits in Hollywood. She is telling me I should be your best friend, hang out with you, what a good influence and help you could be. Our savior who has returned to Middleview,” he said.

His effusive praise made me uneasy, straddling into obsequiousness. I needed music.

“Siri play John Coltrane on Spotify,” I commanded.

They Say It’s Wonderful, Mr. Coltrane on saxophone.

He watched me walk. “You are in good shape man. Do you do a lot of squats?” he asked.

I sat down to hide my ass.

“Yeah, pretty much I’ve lifted for years and run and now I’m riding my bike. Sometimes on that trail along the old railroad tracks that goes past Temple Sholom,” I said.

“That’s a nice trail. When the weather gets warmer and the snow melts, we should ride on it. My mom told me Philippe is in France,” he said.

“How does she know that?” I asked.

“I guess they’re friends on Instagram,” he said.

“How old are you?” I asked.

“Next month I’ll be 18. I can’t believe it. Like a full-blown adult male. Almost done with puberty, still growing though,” he said.

“Should we call your mom?” I asked.

“Why?” he asked.

“Just to let her know where you are,” I said.

“I texted her I was coming here. To discuss college, hang out,” he said.

He had come over and knocked at the door, uninvited, the way we all did in the 1970s. I’m sure he didn’t know that this had provoked my nostalgia, like an unlocked door or home delivered milk.

“Are you and Philippe exclusive?” he asked.

“Monogamous? Do I have to answer that?” I asked.

“Yeah. Do you ever fool around for your own amusement?” he asked.

I wanted to devour him, take him into my arms, but I used every fiber of self-control to restrain myself, to feign disinterest in sex.

It was like I was 18 again, when I had to pretend not to be gay, to reign in my desires, to deny my own impulses, to hope that nobody could guess.

He knew what he wanted. He knew what I wanted. But we just sat there, in our frozen passion, each one unable to make the first move, terrified of the consequences.

“Philippe seems cold, very formal, like he belongs in France, maybe sipping a glass of wine and smoking a cigarette,” he said.

I laughed.

“We are honestly in a separation now. I can’t say if it’s permanent. But I’m trying to behave,” I said.

“Why? If you want to have fun just do it. Nobody has to know,” he said.

“What kind of fun?” I asked.

He lifted his sweater and exposed his chiseled stomach, eight square abs, smooth and hairless and dark skin. I sat in a chair and just stared.

“When is your 18th Birthday?” I asked.

“February 19th. Less than a month. Can I ask you a question about Hollywood? Is everything a casting couch?” he asked.

“Some people do it. I can’t speak for everyone. I didn’t get ahead that way. I worked behind the camera. I wasn’t particularly good looking. I just had smarts, some writing abilities, went to Harvard, had connections,” I said.

“And you’re Jewish. I’m sure that helped. Especially in Hollywood,” he said.

His comment jolted me like an anti-aphrodisiac, brought me back to quandary of how to approach his desecration of the synagogue, and whether confrontation with it would destroy his future, if it were ethical for me to speak up and reveal what I witnessed that day on the bike trail.

“People want to be judged for who they are, their own character, not their ethnicity, religion or for that matter their sexuality. Do you want to get ahead in life just because of the mere accident of existence that made you a Black man?” I asked.

“No. I don’t. I want respect for who I am, not because I have dark skin,” he said.

“Should I help you if I could because you deserve it for your skills and hard work? Or should I just say give this Black boy a job and give him a break because he’s Black?” I asked.

“No that’s racism. But some people got a leg up on others because they’re white and Jewish too, like a double benefit. Jews run Hollywood,” he said.

He thought he was reciting facts, but every time he said Jewish, I felt angrier.

“Do you think if I knew someone committed a crime of arson, I should report it? Or should I stay silent because the arsonist is Black? How about if that arsonist was just accepted to Harvard? Should I shut-up and keep that crime secret?” I asked.

“Please Cole. Please don’t say anything. I don’t know how you know but I was just trying to see what it felt like to be a German in the 1930s. It was stupid but I was just testing myself and pretending to live in the part. I was acting. It wasn’t real. And when I broke the window and poured gas into Temple Sholom and lit a fire, I just got the hell out of there and prayed to dear God nobody would know anything! There’s no temple there anymore. The building was empty. I was just doing a Hollywood recreation. Please don’t report it!” he begged.

He started to cry and his green eyes turned red and then he sobbed loudly.

“Don’t cry. You did a despicable thing but nobody was hurt. Maybe you learned a lesson,” I said.

“I was trying to put myself into the position of the persecutor. To try and understand it. It sounds sick, but I was using my creative imagination,” he said.

Maybe it was the brushed pink sweater, the purity of the white denim, the soft, sweet face of the gay child with green eyes, child arsonist of the temple, off to Harvard in the fall, I had not the heart to hate him. I wanted very much to forgive.

“Come here. Let me hug you. I’m not going to say anything. I love you. You are safe with me. I promise,” I said.

We both stood up and grabbed a hold of each other, and he cried and cried and dug his hands into my back, pressing so hard, and holding me so close it seemed he could not let go.

“It would break my mother. She’s worked so hard and then to have me disappoint her. I know I sinned, I beg for mercy, I’m not a bad person, just a dumb fool. I was acting an evil part to see if I could perform it,” he said.

“What did you learn? That you can hurt people who you don’t want to hurt?” I asked.

“You’re the last one I would hurt. I need you and your forgiveness,” he said.

“This is our secret. Friends for life,” I said.

April is Here

The trees were bare, the nights were cold, but daffodils were everywhere so when the Farmer’s Market opened in the middle of April hesitance gave way to hope.

I didn’t expect much, maybe some lousy Illinois radishes.

I walked along Central, past Starbucks, canvas bag in hand, thinking of Tommy whom I hadn’t seen in two months.

Philippe had come back to live. But he slept in another bedroom and we lived as roommates. He came and went with few words.

I learned, walking past her bungalow, that Miss Frisch had died. Her front door was open and a blanket wrapped piano was being loaded by two men onto a truck.

The executor of her estate presented a gift to Middleview: a new nature center and wildlife preserve on the site of the old Temple Sholom.

People who knew nothing factual but were angry at the Jews for hoarding their ruined property until the highest bidder came along were delighted that Miss Frisch was unveiled as the true owner. They had never met her but were sure that she was a person of rectitude, incorruptibility and generosity.

Rumors and public opinion are how we decide what’s real.

The first farmers market of the year, completely organic, was set along the sidewalk in front of the petrol pumps at the Shell Station. They had more than radishes. They had spinach, peas, rhubarb, asparagus, and goats milk soap made right here in town. And strawberries from Oxnard, California only two weeks old.

I picked up a blue bar of goats milk soap and smelled it. Liz Dewey came up to say hello. She wore a red wool coat over jeans and suede boots and held a WTTW public television canvas bag with carrots, lettuce and other vegetables.

“Cole Taro where have you been hiding?” she asked.

“You were supposed to come in for a follow up. I hope you’re taking your Lipitor,” she said.

“I was going to book something this week. How’s your family?” I asked.

“Tommy is definitely going to Harvard end of summer. I’m so nervous now. It’s what I wanted and what he wanted and now that it’s here my heart is breaking to see my first born off. Have you talked to him?” she asked.

“No. After Philippe came home, I got busy,” I said.

“Are you two getting along? I hope you are,” she said.

“It’s icy but I’m trying to be more understanding,” I said.

“I know you and your partner are busy, but it would be so nice if you could see Tommy,” she said.

I really, really wanted to see him, but not for educational counseling.

“He cares about you. He really looks up to you. And I was hoping you would be closer to him. Because he has no relationship with his father Rod. None at all. I was secretly rooting for you and my son to become buddies, to hang out, because you have so much in common, so much he can learn from,” she said.

“Where is Rod? In prison?” I asked.

She burst out laughing.

“Prison?” she asked.

“I thought he was incarcerated,” I said.

“Really Cole. Really! My ex belongs in prison. But unfortunately, that arrogant, abusive and physically violent man, who has no relationship with his sons, lives in luxury at 1500 Lake Shore Drive. Roderick Dewey is a venture capitalist. You can look him up as one of the top 50 Black Chicagoans in the business world. He has tens of millions of dollars, a 6-bedroom penthouse with 7 bathrooms, but he will not give me a cent because I refuse to let him punch my jaw, slap my face, belt my boys with a leather strap, and threaten me with a gun. I’d rather live on the street then smile and take that fucking man’s money,” she said.

“I didn’t know. I’m so sorry. Why did I think that?” I asked.

“You relied on stereotypes. You ain’t the first,” she said.

We walked Central, turned right on Linden, the street of all the churches: St. John’s Lutheran, St. Mary’s Catholic, All Saints’ Episcopal, and Middleview Methodist.

Their signs advertised their multilingual services in Spanish, Mandarin, Korean, Vietnamese, and Tagalog.

“So many languages now. Not like the old days,” I said.

“I feel glad to live in Middleview. I feel at home here. What about you?” she asked.

“I’m sort of still in exile,” I said.

We turned back to Central and stopped in front of Starbucks and her apartment.

“Before Tommy goes off to school, let’s have a dinner with everyone. Maybe we can do Korean barbecue at Old Seoul, my treat. You haven’t met Kenny or Patrick, my two younger sons. Patrick is 13 he wants to be an architect. Maybe Philippe can talk to him. And Kenny is 15, hilarious, he’s doing a TikTok thing, and he has a lot of skits, and people follow him. I think all the boys are into promoting themselves, doing things that get viewers, and hopefully some income. This is how it is now. Middleview is Hollywood too,” she said.

“Yes, I suppose it is. There is no escaping it,” I said.

“Well good-bye. Don’t forget to make that appointment with me. Talk soon,” she said and then she went up to her apartment.

And I went home, a stranger in my own hometown.

# # # # #

You must be logged in to post a comment.