The Getty has 45,856 digitized photographs of Los Angeles by Edward Ruscha.

I went to look at just a part of it, May 1975 (3,724 images).

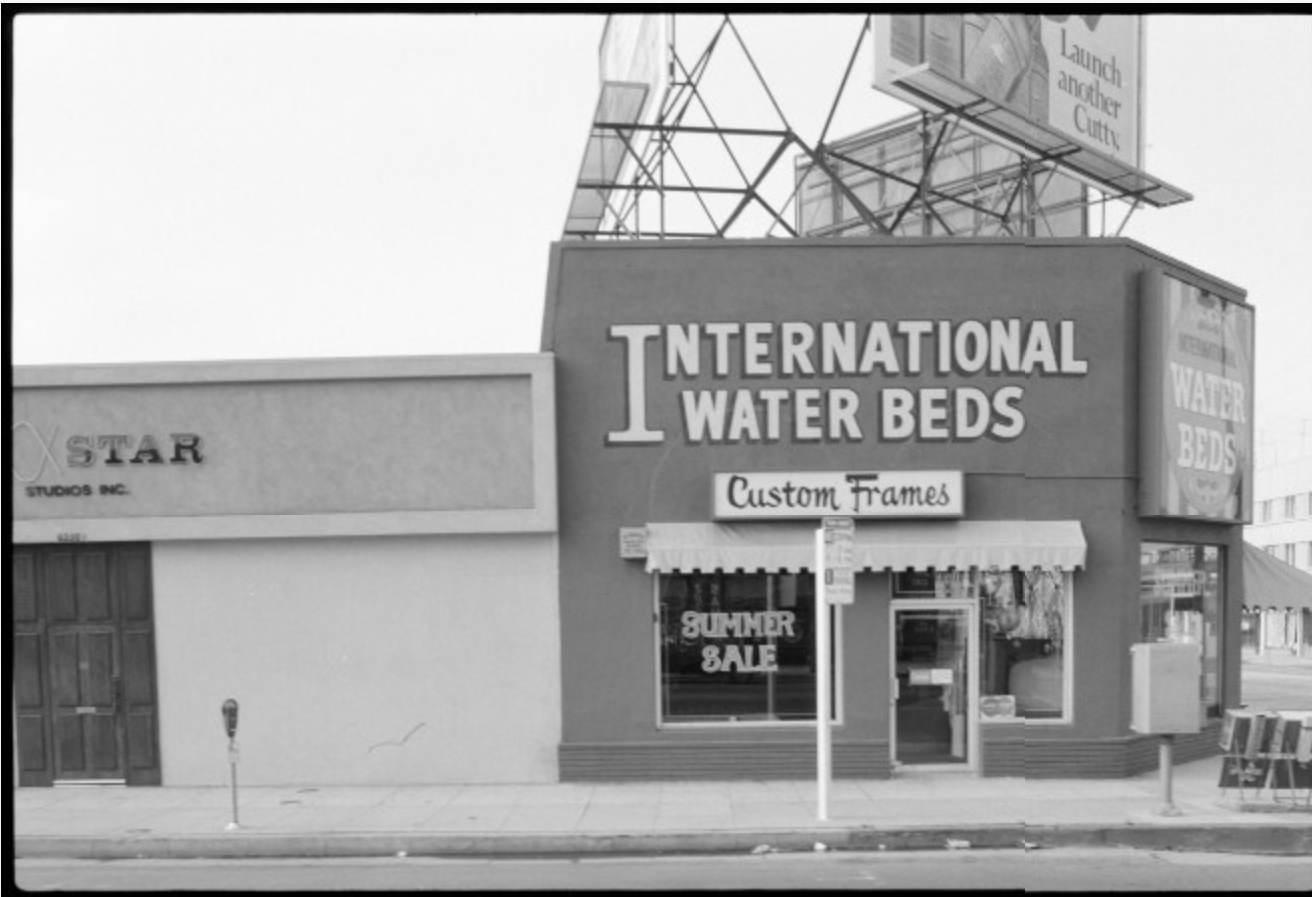

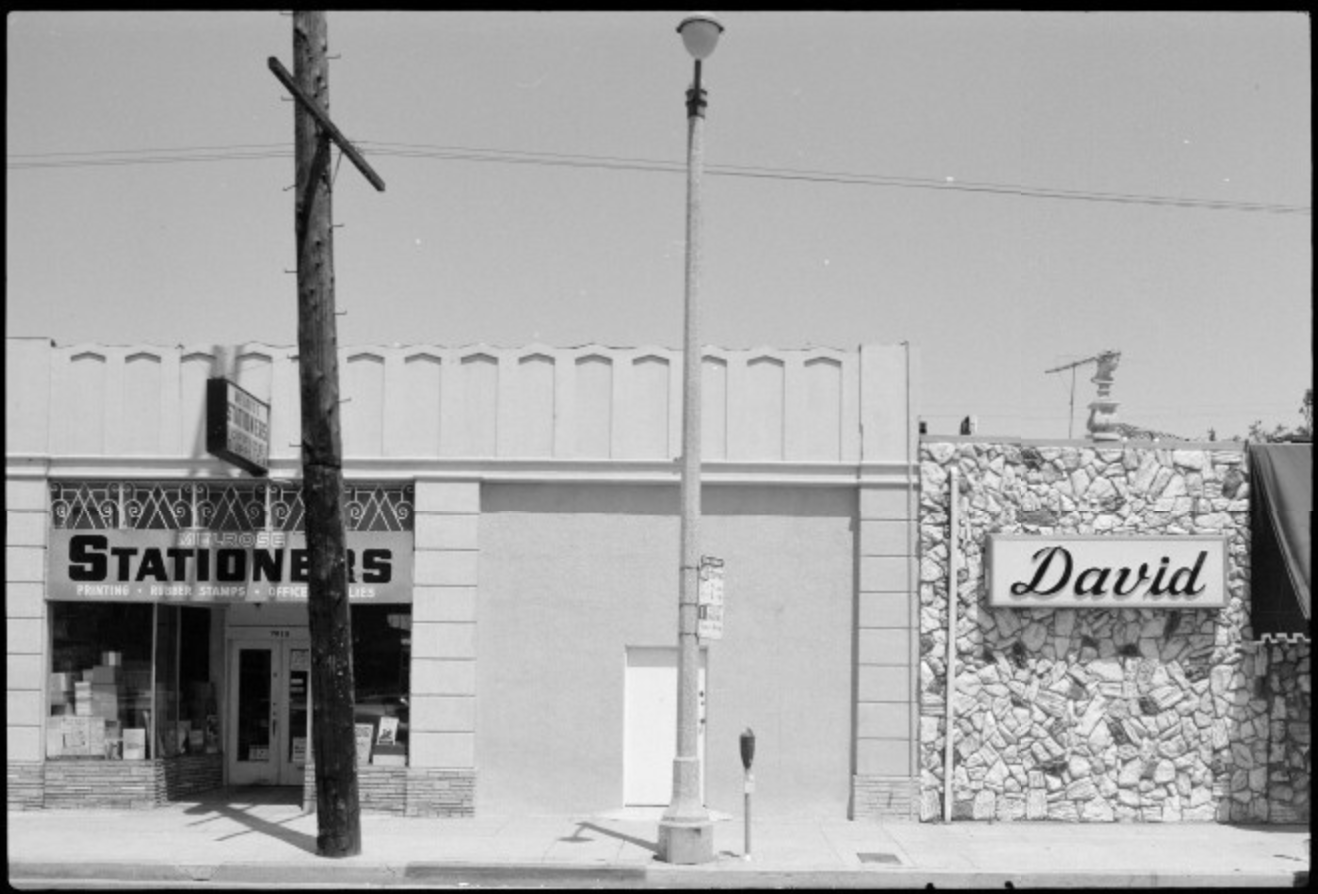

There are black and white photographs of entire stretches of streets in our city, for example every structure along Melrose Avenue for miles.

Many who possess far greater insights than I will concoct profundities about these pictures, connecting them to politics or music or the decline of the West.

They will project onto the photos whatever template of modern ideology they wish.

But I think these photos just are. They are the exact thing they show. And that is what makes them brilliant. For they are the essence of Los Angeles, a homely and free place of ambition and anomie.

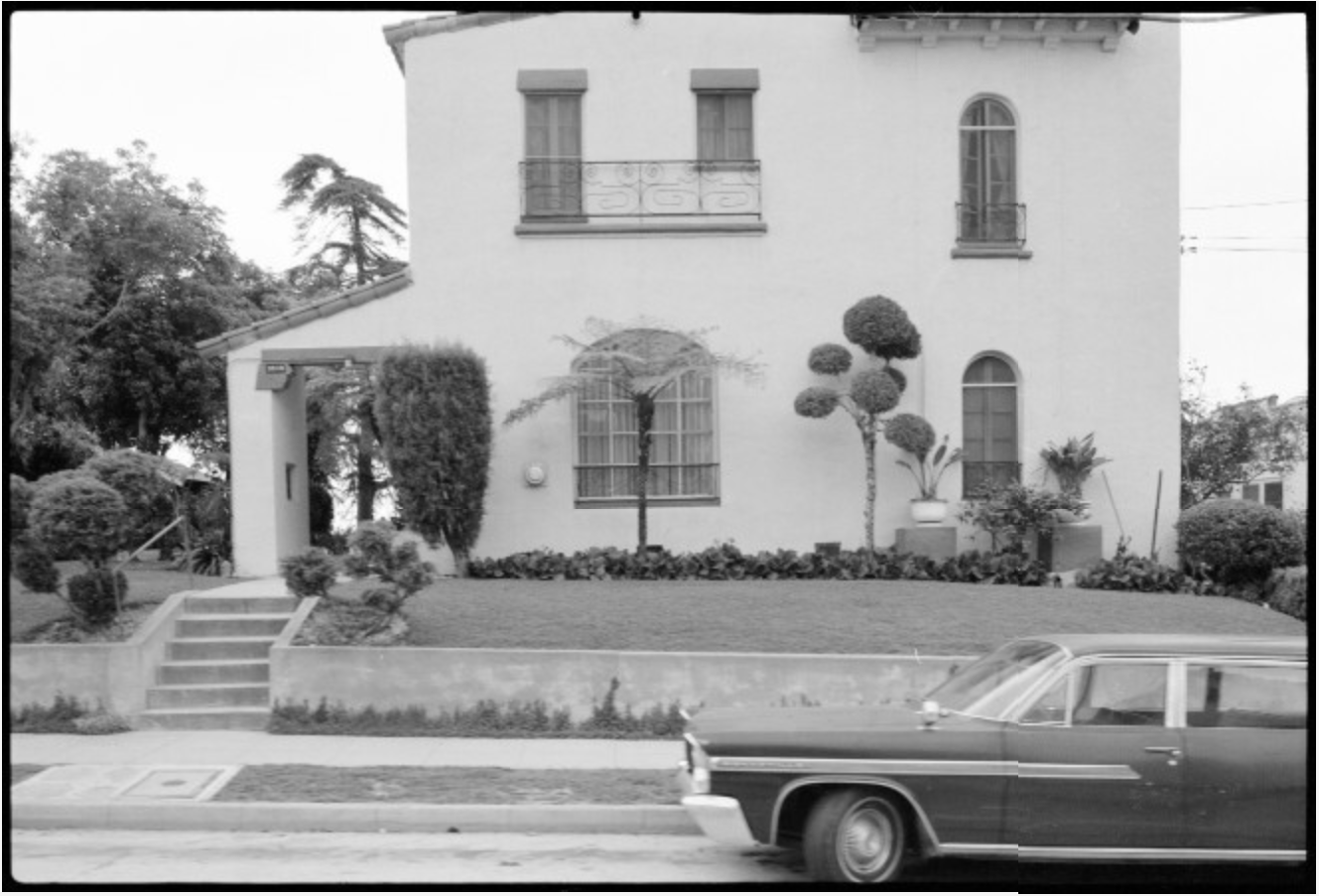

There is 3910 Melrose Avenue with a circa 1964 Pontiac parked in front of a 1920s Spanish Style house with arched windows, topiary and a cement walled lawn.

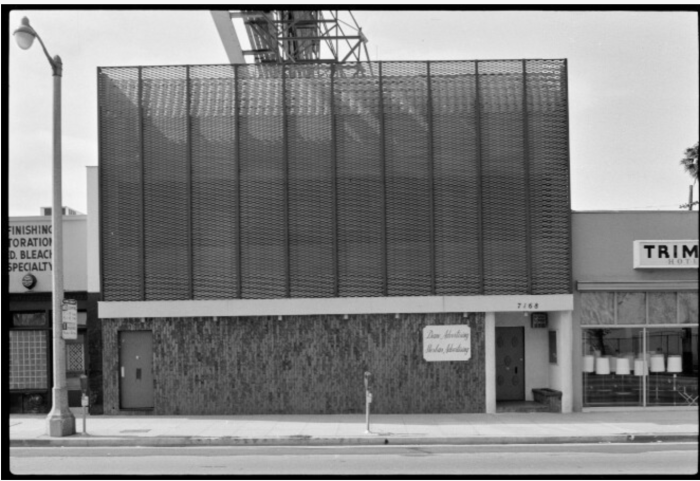

At 7168 Melrose there is a commercial building, with a 1960s decorative screen covering over a 1920s red tiled roof and stucco façade.

Most of the photographs juxtapose car and architecture. That is the recipe. It makes us long for youth, ache for what has passed, and imagine what it might be like to drive a ’74 Camaro down spotless Melrose, listening to a Doobie Brothers 8-Track, and stopping off to pick up a bag of gourmet Brazilian nuts at Iliffili.

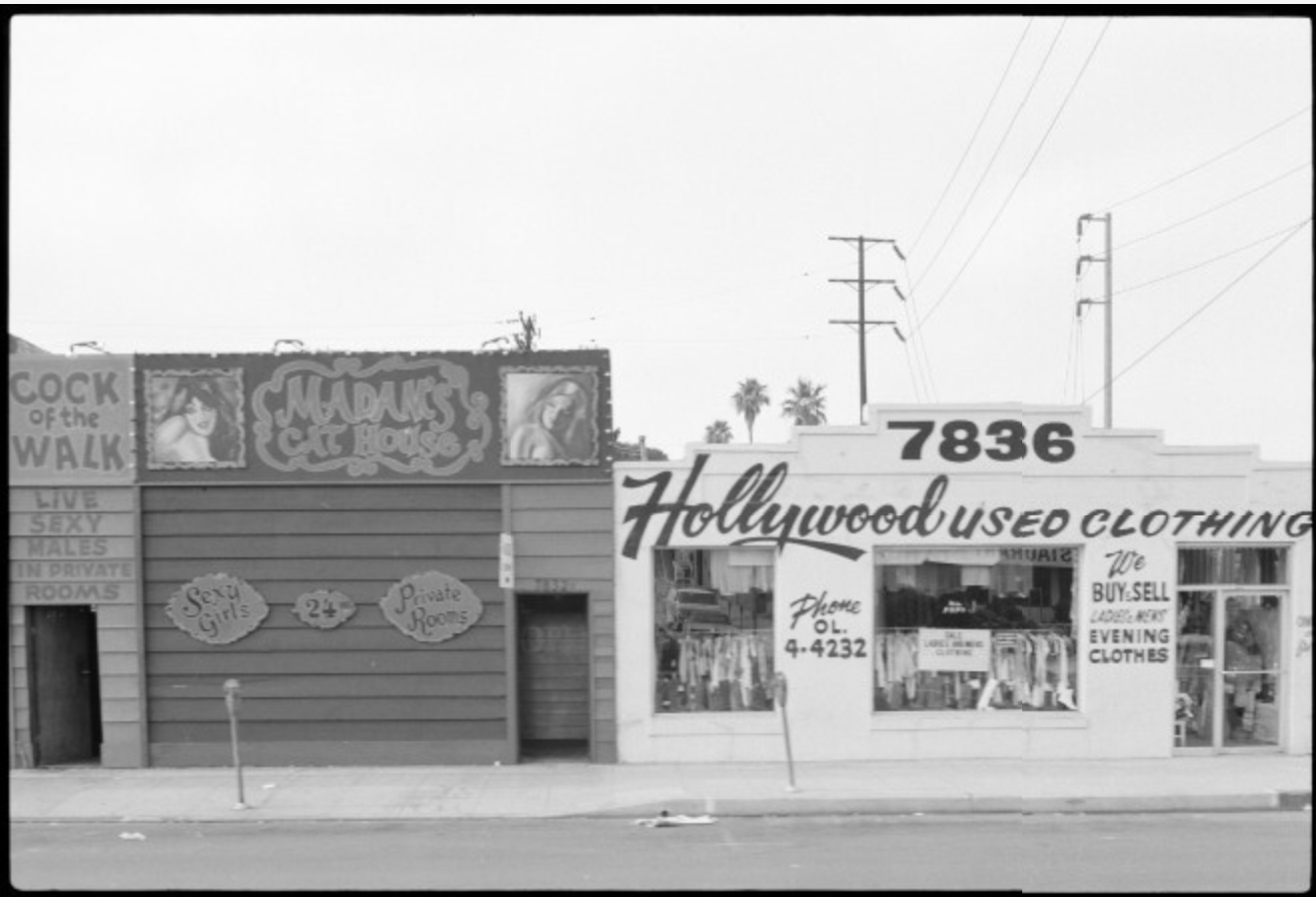

Sex was open and advertised in 1975. Cock of the Walk had live sexy males in private rooms. It was next door to Madam’s Cat House with sexy girls in private rooms. If you messed up your clothes you could slip in quickly next door and change into a new pair of old jeans at Hollywood Used Clothing.

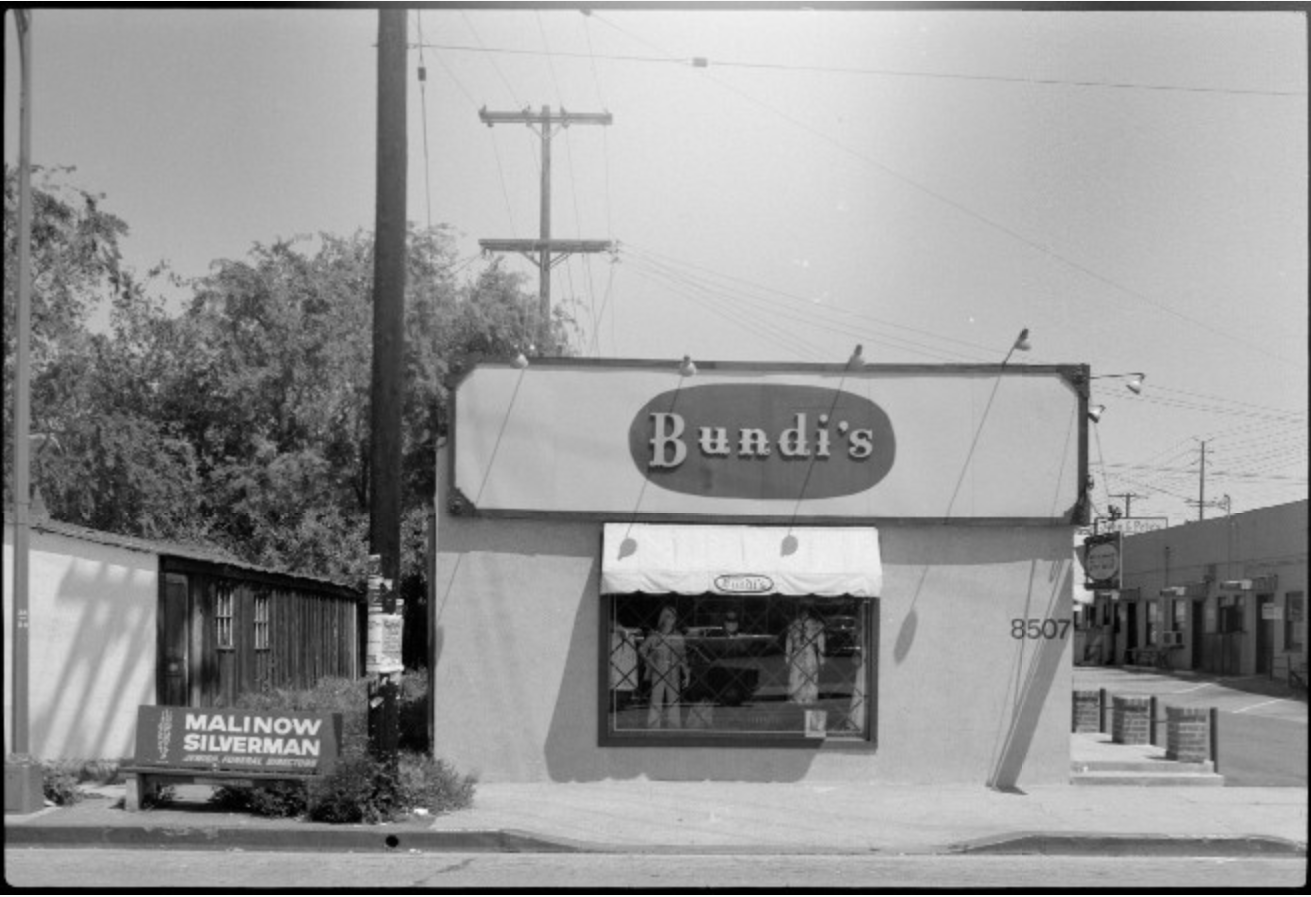

Bundi’s at 8525 Melrose had stylish looking clothes. Just outside, a bus bench advertises the Jewish funeral services of Malinow Silverman.

Along 8650 Melrose, a 1969 Cadillac convertible, and a 1964 Chevy Impala coupe, are parked on the curb in front of several young, hip stores offering haircutting, needlework, a rock gallery, and Ruthe Lee Richman’s Art in Flowers.

A few doors down, Irving’s Coffee Shop served Pepsi-Cola. What kind of menu did they have ? Imagine your dining choices in 1975 Los Angeles, a 90% white city prior to the mass immigration and cuisines of Vietnamese, Filipino, Burmese, Persian, Haitian, Korean, Guatemalan, Honduran, Brazilian, Malaysian, and Sri Lankan peoples.

Imagine a city where so much was tolerated but where nobody lived under bridges or slept alongside freeways, and bus benches were used by bus riders.

Having trouble sleeping? Stop by International Water Beds. Writing letters to friends? Pick up some custom letterhead at Melrose Stationers. Is your cane chair falling apart? Frank Lew at 706 N. Orange Grove will repair it.

There are a lot of photos to look at. Like everything else these days we compare it to 2020. Even 2019 seems more like 1975 in the take-for-granted-liberties we had before the pandemic.

And now we close with these lyrics:

Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose

Nothin’, don’t mean nothin’ hon’ if it ain’t free, no no

And, feelin’ good was easy, Lord, when he sang the blues

You know, feelin’ good was good enough for me

Good enough for me and my Bobby McGee[1]

[1] Kris Kristofferson-songwriter

Janis Joplin-singer

You must be logged in to post a comment.