In 1931, two years into the Great Depression, Frederick Lewis Allen published his history of the 1920s, “Only Yesterday” covering the period from the end of WWI until the market crash, in October 1929, that plunged the world into poverty. The American economy would not revive until war and destruction obliterated Europe and engulfed Asia, and after the suffering and the debacle of that period, enlightened leaders vowed to never allow world war again.

So, here we are, now.

We seem, again, to be living in the most exciting of times, a moment of collapse when people are without money, in fear of their health, and watching the world outside collapse. Families and friends are unwittingly jammed up inside, fearful of intimacy, terrified of shopping, petrified about their money, unable to sleep at night, and looking for some savior vaccine to end this nightmare.

An incurable contagion devastates the lungs, drowns us, and we die alone. Please, somebody, do something.

We look up high to the presidential podium for answers.

But we hear the cries from the asylum.

Every aspect of normal human life is now that moment in the horror movie when The Lone Girl goes downstairs into the dark basement after she hears a noise.

7.5 billion are now The Lone Girl.

We are home with children or aged parents, or quite alone, with nobody. We are sitting at computers, trying to work or forget; obsessed over disabled relatives in group homes; monitoring children playing in the yard when the wind is blowing.

We can’t go to the gym, to the mall, to the coffee bar, to the park. We do push-ups if we can, and we lay on the couch all day until we try and sleep but we can’t.

We are on guard receiving a package at the door, opening a letter, putting hands on a steering wheel, touching a doorknob, wiping down a mobile phone, cleaning a countertop, eating a banana with unwashed hands. We dare not open a window to let in a virus or forget to sanitize a salt shaker.

A text message, “Call Me”, is alarming.

Everything is terror.

We are told, now, too late, to wear masks when we leave the house. Before they were of no use, now they are essential. We are told to use hand sanitizer, but what if someone behind us, at the grocery store, unmasked, sneezes or coughs?

In the midst of this darkness, I learned, strangely and horrifically, that one of my friends from MacLeod Ale, Drew Morlett, 37, had been stabbed to death last Sunday, by a woman, during a fistfight with a man, at a party given by a nurse (Drew’s girlfriend?) who unwittingly invited the murderer over to her apartment on Kester Street.

To attend a party during a pandemic is foolish, but just being foolish is not reason enough to justify murder. In poetic justice, all the fools at the party would catch the virus, their punishment for violating what we all know we must not do.

Though I knew Drew for five or six years, I hardly knew him at all.

We had met at MacLeod Ale, and then we’d hang out, always by coincidence, never by intention.

From what I knew, he lived walking distance from MacLeod, with his family, near Hazeltine and Oxnard. He had a raspy voice, with a sound almost frail and hoarse, so I nicknamed him “The Raspy.” He was a townie, like many at MacLeod, adults raised in Van Nuys who never leave Van Nuys. MacLeod was his parish.

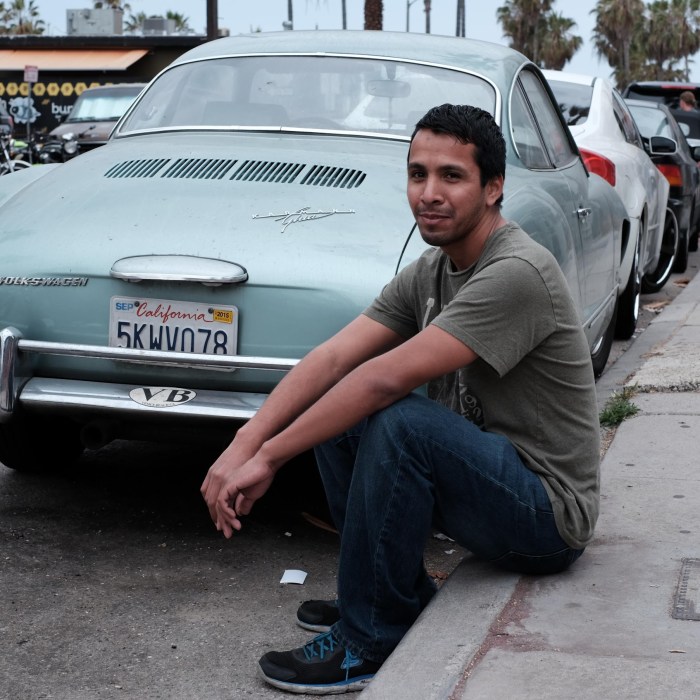

On Saturday, June 27, 2015, The Raspy and I went to Venice, this time by intention, to take photographs and drink beer at Whole Foods, beer served by bartender Drew Murphy, an amateur expert on beer, who used to casually serve us oysters, shrimp tacos and other good foods that somehow never ended up on the tab.

That bar at Whole Foods on Lincoln had become a place I went to often, especially in the year 2014 when my mother was laid up in bed in Marina Del Rey, dying of lung cancer, and I’d go down and see her, and then stop off at Whole Foods and self-medicate, and drive home slowly in the night air, always careful to let the beer burn off before I drove, sometimes going up Beverly Glen, the long way, windows open, as Jo Stafford or Frank Sinatra played, and the profusely growing night jasmine floated in.

The Raspy worked in computers, or fixing computers, or something like that, I never knew. He was gentle, and short, and thin, and a twin, with a twin brother. He had olive skin and wore olive t-shirts. I felt like I could have been his best friend, but we never talked about anything, really.

Others at MacLeod, people who drank nightly, or played darts, knew him better. I was not one who played darts or drank nightly, and last year I only spent some $800 dollars at MacLeod, for all of 2019, and I would guess Drew spent considerably more, though I don’t know, and to speculate is to lie, so I can’t say.

One time I saw Drew Morlett and he said he was laid off and looking for work. Another time he said he was living with his girlfriend on Kester. One late night he called me and invited me out, and it was after 11pm and I didn’t go. He was known at other bars, other dart places, and in other drinking establishments, and it seemed he was out and about and all around the city, going out and about and all around the city.

Until he died last weekend.

Now he is dead, dead in the way Van Nuys kills you: in obscurity, senselessly, ridiculously. That weekend, two days before he was stabbed, another man, a homeless man, Dante Tremain Anderson, 35, was killed the same way, by knife, not far away, on Burbank Boulevard in the Sepulveda Basin.

Before I learned about the identity of the second victim, Drew Morlett, I knew about the first and second murders. And in my mind, they were indistinguishable. Just anonymous and tragic and forgotten.

Now one of the dead I had really known, and hugged, and laughed, and drank with. He had siblings, parents, friends, and they all mourn his death. I cannot feel the grief his family carries, and they have my deepest condolences.

On June 21, 2015, a year after MacLeod Ale opened, that brewery held a big party.

Drew Morlett was there, and so were hundreds of other people. They lined up to buy tickets, to sample brews from guest taps, to listen to lectures by brewers discussing brewing, to meet other enthusiasts and lovers of craft beer.

I took many photographs that day, and now they look remarkably dated.

It is not only that we are presently, legally restricted from gathering, but that we are older. We are now incarcerated by grave and ominous fears and worries, and to drink beer in a crowd and listen to music and get drunk, that is our fondest hope for what we might do again.

We hope, not only to be well, but to live, to be in this world, not banished from it, and to return to happiness and blithe ridiculousness, and even carelessness and stupidity. We should not have to die for our love of each other, we should not have to die because we partied, or touched our face, or went to a movie, or shopped for food, or cared for a sick person in hospital. Somewhere there is a profound lesson in all this, but I can’t quite fathom it.

I have to go wash my hands now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.