In the 1960s, the swamps of south Venice became a multi-million dollar building project that culminated in what we now call Marina Del Rey.

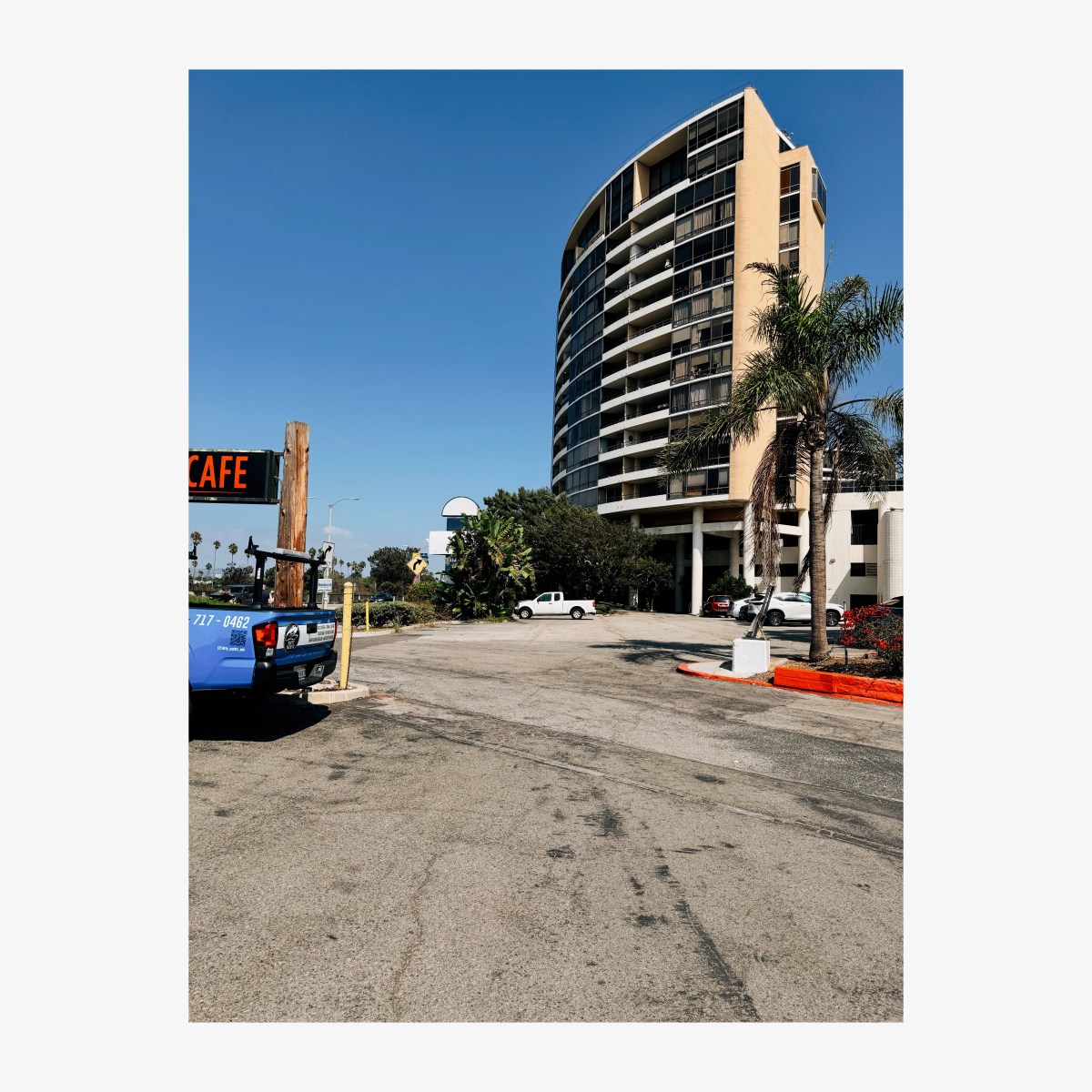

Pleasure boats, yacht clubs, nautical facilities, circular high rises with balconies overlooking the harbor, landscaped roadways with palm trees, office buildings, pharmacies, tennis courts, a hospital, a fire station, a library; and many restaurants overlooking the yachts, sailboats and motor boats.

A district devoted to tanning, drinking, carousing, love making, and living the good life amongst airline pilots, stewardesses, restaurant workers, aspiring actors, and retirees. The 1960s dream of accessible pleasure for anyone white with a convertible.

They even built the 90 Freeway to get people in fast, before the boat left the dock. Imagine the high quality of life 60 years ago, when a new freeway was affordable and considered the highest and best use of land.

From its inception, Marina Del Rey feigned a public purpose while raking in the dollars fencing off the best parts for private use of yacht clubs and apartment dwellers. Docks are locked up and there are many barriers to prevent the use of the harbor for the general public unless you are there to purchase a dinner and drinks on a boat, bar or restaurant.

Over the years, there have been community projects to create usable public space, such as Yvonne B. Burke Park on the north side of Admiralty Way which has athletic equipment, bike roads and jogging paths. That park too has recently been incarcerated when Bay View Management built a cinder block wall that closed a public access point behind a Ralph’s store on Lincoln Boulevard.

God forbid a pedestrian in a park might access a supermarket on foot.

Other luxury apartments, understandably fearful of crime, vagrancy and violence, have illegally built obstructions along their land to prevent the park from becoming a way to enter their properties.

Every few hundred feet, the green parks become parking lots. An athlete running, riding a bike or rolling skating will eventually stop at a busy road where vehicles speed by at 60 miles an hour. And other cars and trucks will be entering the parking lots or exiting, creating additional hazards for the non-driver.

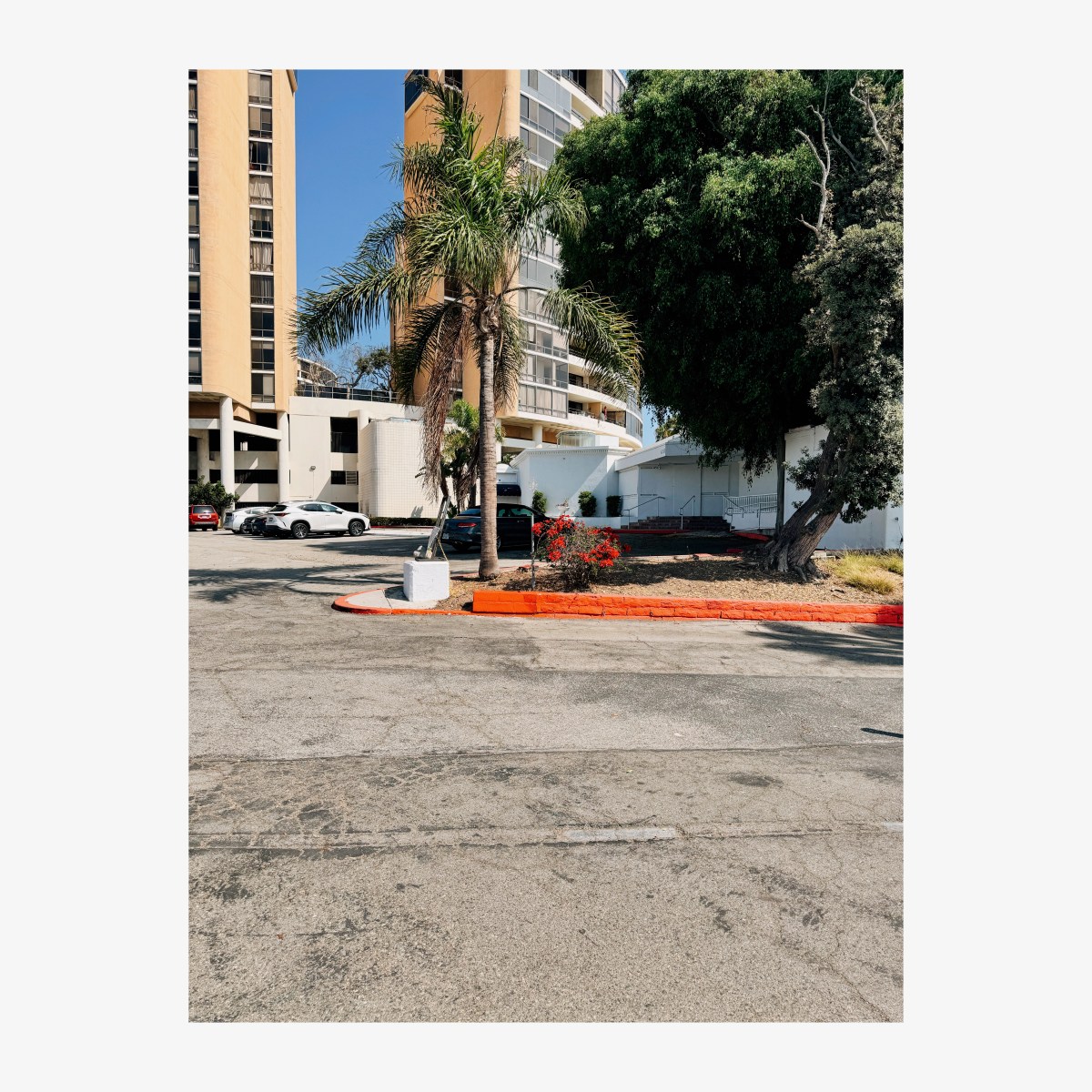

The big, popular restaurants, anchored in seas of asphalt, offering seafood, steak, alcohol, valet parking, and private parties to corporate diners and red nosed, melanomatous men in Tommy Bahama, have all gone out of business. Café Del Rey and Tony Ps with their crumbling, dated, Brady Bunch style restaurants are empty. The cigarettes, cigars, Aramis and lounge singers gone with the wind.

The great pandemic meltdown which has stolen our lives, taken our movie theaters, pillaged our department stores, and defecated upon our civic dignity, has now obliterated the big dining establishments of Marina Del Rey.

These popular places, that seemed immune to time, forever serving enormous plates of grilled lobster, prime rib, baked potatoes, cheesecake, ice cream sundaes and voluminous cocktails are now dead. Silent as Hiroshima after the bomb, these outposts of high on the hog, intoxicated living were ailing, out of fashion, and are now exiled from our spartan, self-consciously healthy era.

For a pedestrian who is trying to stroll one mile of the harbor west from Bali Way to Palawan Way, with the boats in view along the south walkway, there are several private obstructions that make it impossible to complete the walk.

I speak from experience as my friend Danny and I did the walk today.

The California Yacht Club locks up the walkway with their own use of the property.

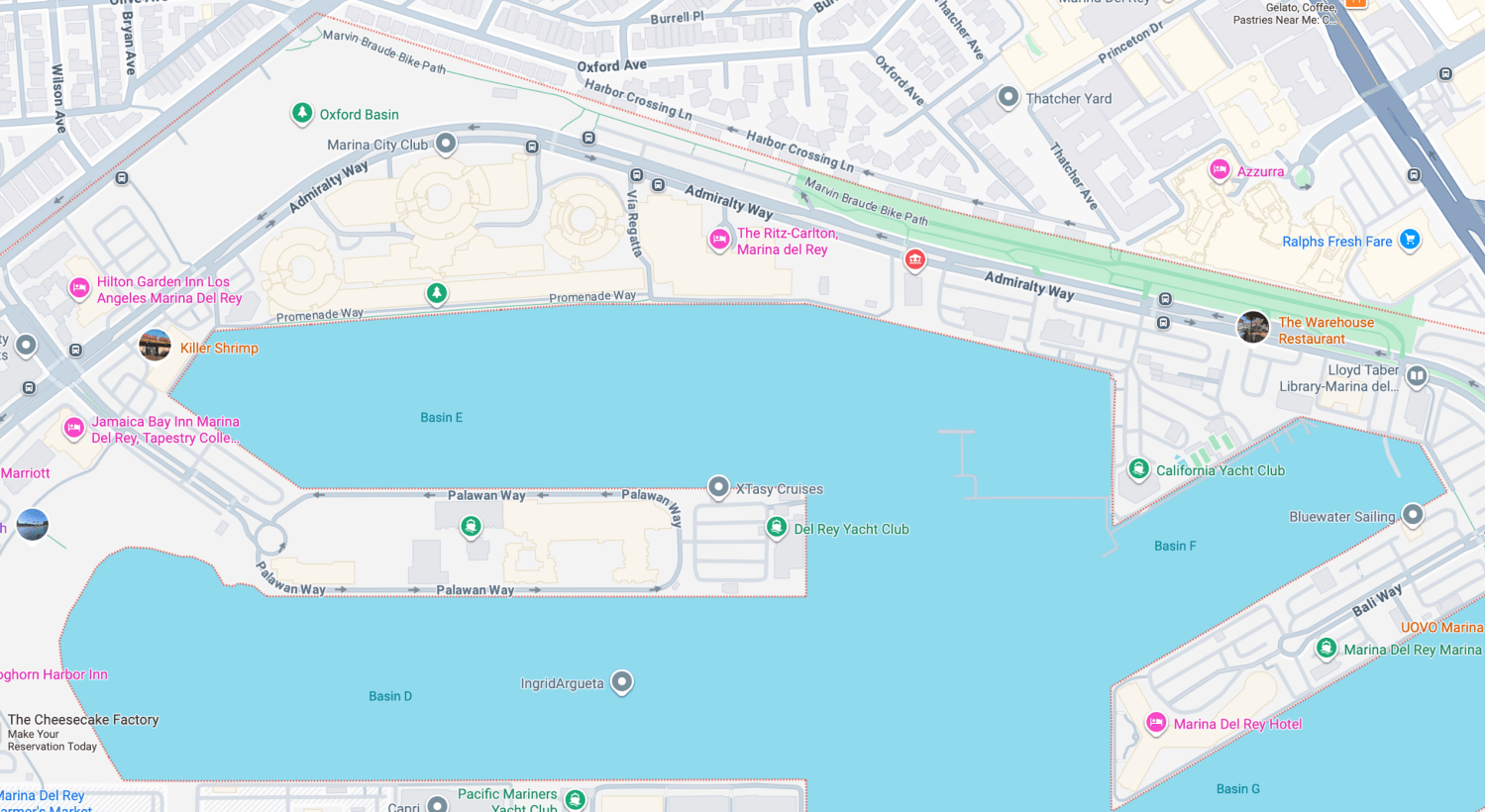

One is forced to detour to Admiralty Way with the unused parking lots of the long-gone restaurants on one side, and the near-death experience of speeding cars on the other.

To reenter the harbor walkway, you find the Los Angeles County Fire Department Station #110 (4433 Admiralty Way) and walk behind the building to rejoin the path along the water to once again enjoy the public recreational qualities that are supposedly there for everyone to enjoy, not just yacht members.

The Marina City Club encompasses three early 1970s high rises which are entered securely by several guarded driveways on Admiralty Way. This complex has swimming pools, tennis courts, a convenience store, but is threatened by similar structural defects that brought down the Surfside, Florida condominium in 2021, killing 98 persons.

For now, residents who own property there pay high HOA fees, and even those who bought in cheaply face repairs that will surely cost collectively in the hundreds of millions of dollars to make these three, 55-year-old buildings safer in a location where tsunamis and earthquakes are always visiting unexpectedly.

Concluding the walk today, we went north along a dirt path on the west side of the Oxford Basin “Wildlife Refuge” which connected to Washington Boulevard.

As we passed a vagrant man sprawled on wall, shopping cart and garbage nearby, my friend Danny shouted, “Get going, walk faster.”

Danny had spotted a handgun in the vagrant’s hand.

Just another reminder, if any is needed, that nobody should assume that this is a safe area, regardless of how much homes sell for. The demoralizing and unsanitary aspects of Los Angeles are all around, because we live in perhaps the dirtiest metropolis in the United States, one that believes public trash camping is a civil right and mental illness is only a danger after it kills.

How this city will present during the 2028 Olympics is something Orwell would have pondered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.