Cancer, homecare, medicines, hospice, chemo, wheelchair, bone cancer, lung cancer, cough syrup, Oxycontin, Oxycodone, Remeron, Sinemet, Morphine, adult diapers, sponge baths, bowel movements, stool softeners, rehab, oncologist, nurse, radiation, constipation, oxygen, Stage Four, terminal, incurable, cremation.

For seven months I’ve swum in a whirlpool of ugly words.

Yesterday, again, I went down to see my mom at her apartment. One homecare worker was leaving, another arriving. I came in with four bags of groceries and went back to the bedroom.

She was in bed.

The TV was on. I think it was “The View”.

I sat down on the carpet in front of her bed, the only way she can see me, straight ahead.

Bertha came in with matzo ball soup. I ate two bowls. She fed my mom a few bites.

In the afternoon, I took my mom for a “walk” in her wheelchair.

I picked her up, limp and frail, and moved her from the horizontal position on the bed into her chair. Seated now, I put the pedals on, guiding her weak legs and purple feet into position over the pads.

I squeezed a pillow behind her curved back, and pulled her arms up into a zippered sweatshirt. I draped and folded a blue terry cloth blanket across her lap. Sunglasses went over her eyes, a hoodie atop her head.

I pushed the steel chair and the woman in it out of the bedroom, past the front door of the apartment, into the elevator riding down, through the dark parking garage. And out into the brilliant sun, out into the fresh and salty wind.

A key opened the locked steel gate along the long dock where cruisers, sailboats and yachts were docked. Between the boats and the buildings, that’s where we went.

The hi-rise, swinging sixties apartments along the Marina, with their curved balconies, they were made for tanned stewardesses, white shirted pilots, Irish-American boat captains, cocktails on the sea, cigarettes and sex, lovemaking and laughter.

Architects and developers back then, like now, were drunk on youth, novelty and modernity.

Nobody was supposed to get old. Nobody was meant to come here disabled, wrapped in blankets, pushed along the harbor watching other people have fun. Wheels were the Red’68 Bonneville Convertible- not the walker and the wheelchair.

We walked past Killer Shrimp and crossed the asphalt to the other side where they were renting paddleboats and paddle boards. I pushed my mother to the end of a dock inside the lakelike Mother’s Beach.

On the dock, my mother in her chair, me pushing her almost to the edge, a sinister thought entered my mind.

I thought of Technicolor Gene Tierney in “Leave Her to Heaven”(1944) where she let a crippled boy, her husband’s brother, drown in a cold lake.

If I had the evil gene of Gene I might act on hard and cruel impulse and push mom into the water, an act of mercy perhaps, saving her from the eventuality of dying in bed from fluid in her lungs or some other unforeseen killer.

Instead, I pulled back and fastened her brakes. I took out my phone and photographed my living mother motionless on the ocean dock.

Hours later I was at the Whole Foods bar with Travis, drinking a Scotch Ale, listening to a ravishing real estate agent, talk about her teen son’s abusing father, and her fight to cure her child.

Pretty, like the actress Susan Lucci, she grew up in Venice and talked as if she had sold many millions of dollars of houses in the new rich bohemia.

My buddy, much younger, broader-shouldered, deeper-voiced and all man, listened to her as she massaged him with her eyes.

She showed us pin-up shots of her on the Samsung screen, sexy images that made me ask, intoxicated as I was, what exactly she was selling.

Around us in Whole Foods, was the whirlpool of beauty and freaks that swirls in the aisles among the organic fruits and vegetables: tall women, muscular men, old women in running shorts; beards, tattoos and pegged pants, rolled cuffs, razor cuts, canvas bags, kale and 90% cocoa chocolate bars.

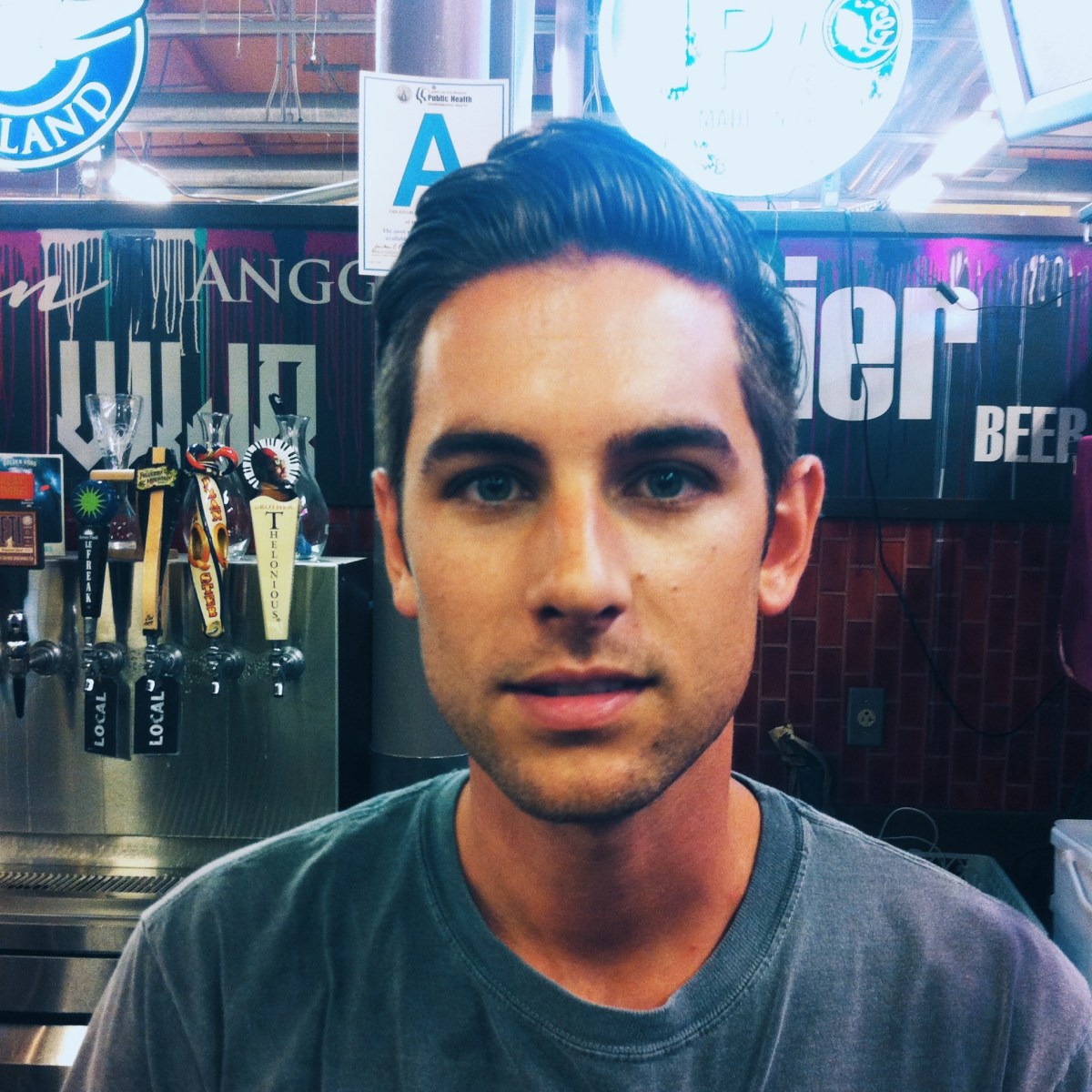

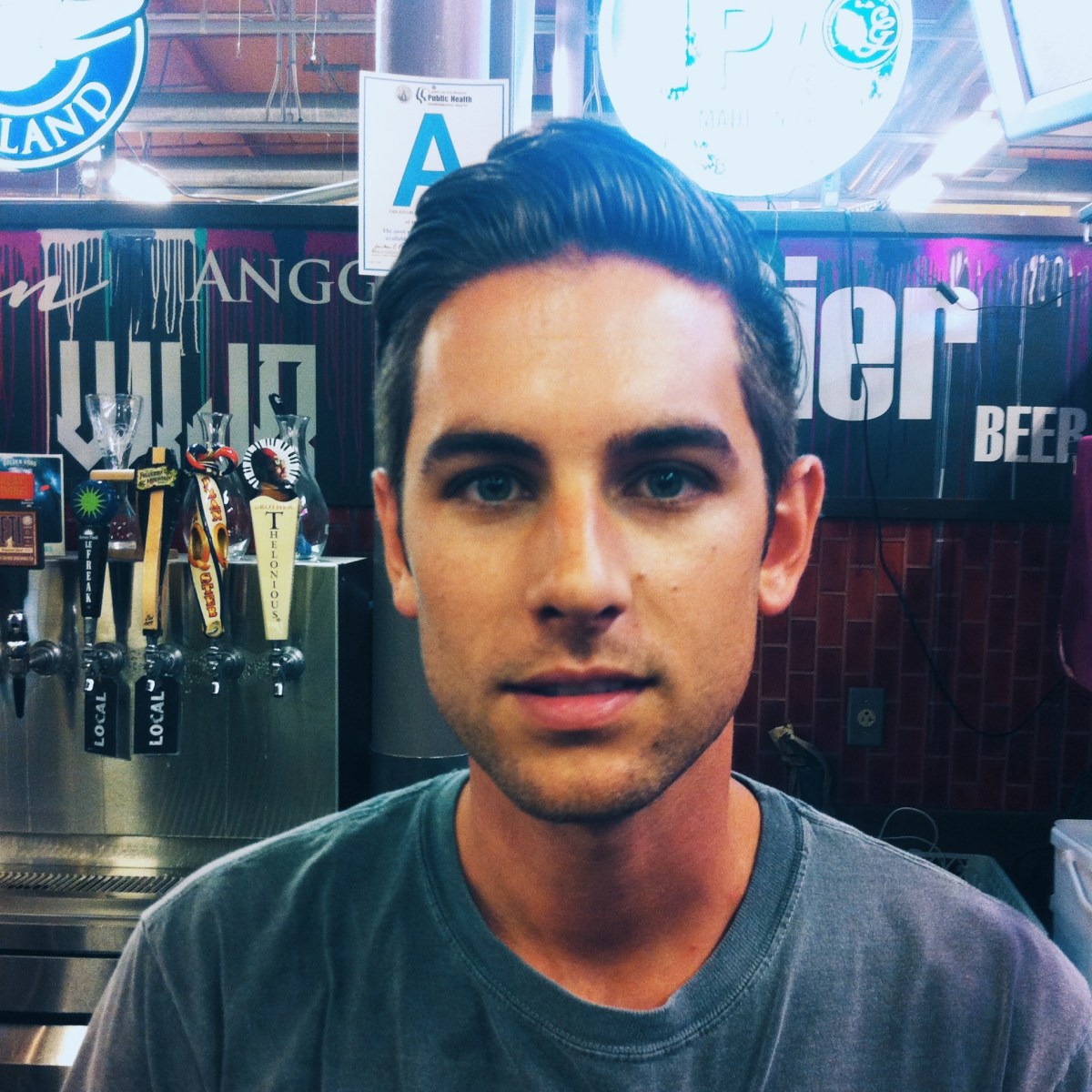

Travis and the real estate agent left, going their separate ways, but I stayed longer, waiting for the beer to wear off. I amused myself by photographing the green-eyed young clerk Joey.

I am not an alcoholic, but I now can see, with ease, the attraction of numbing pain, blocking sadness, loosening tension. I will willingly submit to its temporal benefits and consoling pleasures.

As I did last night for a few hours after dusk.

One day soon, I will come down here to Venice and Marina Del Ray.

And my mother will be gone.

And I will think of these months, the ones that came about in 2014, where sickness and impending death arrived without warning.

And I will remember the endless summer of insipid profundity, the strange and incongruous times of illness and fun, the months on watch seeing her decline in Marina Del Rey.

Who dares to die in a place where pleasure pushes along unimpeded on bike, in swimming pools, on jogging paths, on tennis courts, at volleyball games?

You must be logged in to post a comment.