© Photo by Mike Meadows via Flickr.

Essay reprint.

Why Do Firefighters Oppose Safe Streets?

By Josh Stephens

February 25, 2024

Ballot Measures , Streets, Walkability

A few days ago, I drove from west Los Angeles to Whittier, a leafy suburb founded by Quakers on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County. Just east of downtown Los Angeles, I got on the 60 Freeway and took it to the 605.

I kid you not, every single billboard along this route advertised one of two things: insurance or accident attorneys.

I lost count of the latter. There was Jacob Imrani, Anh Phoong, Sweet James, Morgan & Morgan, and the dean of Los Angeles accident attorneys, Larry H. Parker, who’s been “fighting for you” seemingly since the days of covered wagons. Pirnia Law sponsors UCLA athletics and appeals to the fraternity crowd with the most bro-y slogan in legal history: “putting the ‘lit’ in litigation.” The Pirnia billboard I saw on Friday promised, “We run L.A.,” whatever that means.

(An aside: if you’re going to be an accident attorney in Los Angeles, it is, apparently, mandatory for you or your avatar to have facial hair, ideally a goatee.)

These billboards all make for an ugly drive. Granted, it wouldn’t have been any less ugly if they advertised something else, like soda pop, cigarettes, or, well, cars. What’s remarkable is that, in a county with a $750 billion GPD, these are the only businesses that seem willing to spend money on outdoor advertising. Sadder still: there is a robust market for their services.

Our society is as litigious as it is dangerous.

Between 2013 and 2022, Los Angeles County averaged around 54,000 fatal or injury crashes annually (the vast majority being injury-only crashes). I’m pretty sure the only people who celebrate those statistics are the attorneys. And yet, the crashes persist.

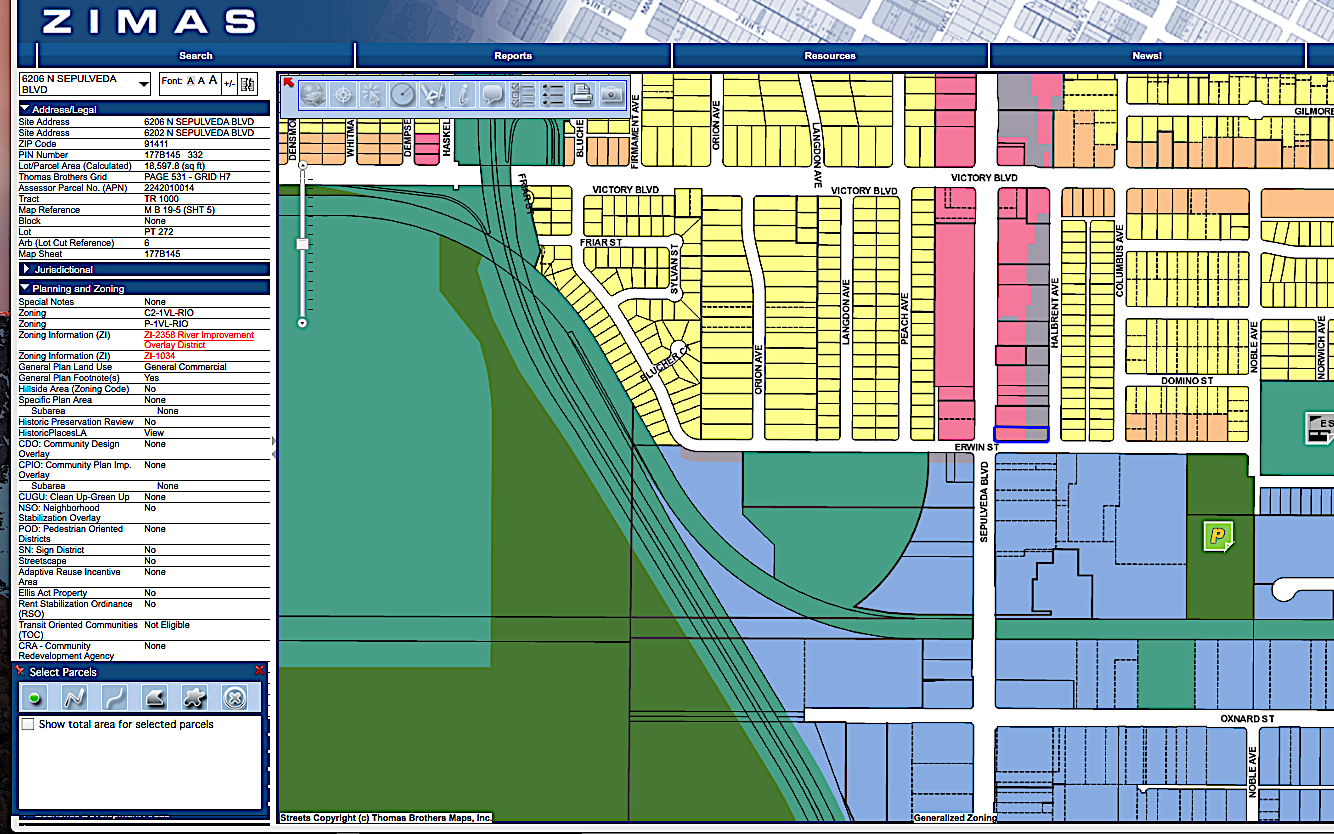

One city in Los Angeles County is attempting to do something about car accidents and, especially, the hazards they pose for pedestrians. On March 4, voters in the City of Los Angeles will consider Measure HLA, an initiative that would force the city to implement its Mobility Plan 2035, which was adopted in 2015. Backers of Measure HLA say that the city has implemented as little as 5% of the plan. Meanwhile, some 300 deaths take place annually on the city’s streets.

HLA promises a revolution in active transportation and the pedestrian realm. We’re talking about enhanced sidewalks and crosswalks; street furniture; trees; dedicated bus lanes and upgraded transit stops; bike lanes; traffic calming; and more. It’s the sort of mobility bonanza that activists and progressive planners have dream about. It could turn at least a few of Los Angeles’s ugly, dangerous thoroughfares into places that people where people just might want to hang out.

HLA will not be cheap. A recent analysis by Los Angeles City Administrator Matt Szabo estimates it will require $3.1 billion. Supporters dispute that number and, of course, argue that the promise of lives saved and streets beautified justifies a major investment.

Now, our friends on the billboards haven’t come out against Measure HLA, as far as I know. Even they aren’t brazen enough for that. And yet, someone else has — the firefighters of the Los Angeles Fire Department.

Let that irony sink in for a moment.

The firefighters claim that many of these street improvements could interfere with emergency responses. “Every second counts. The road diets slow down our firefighters,” Freddy Escobar, president of the United Firefighters of Los Angeles City Local 112, told the Los Angeles Times. “And it will be so much worse with HLA.” In other words: we don’t want a hook-and-ladder truck getting hung up on a bulb-out or squeezed by a bike lane.

I give due respect to emergency responders, and I get that the firefighters have their priorities–especially when it comes to saving lives. But the mobility plan isn’t merely about aesthetics. Its point, in fact, is to save lives: not by responding to accidents but by preventing them in the first place.

In 2023, 336 people died in traffic-related deaths in the City of Los Angeles (half were pedestrians). Meanwhile, between 2014 and 2019, the average number of deaths from accidental structure fires was 14. I hardly want to pit one sort of tragedy against another. But, let’s face it, governance is always about priorities.

And, indirectly, Measure can improve public health by promoting walking and biking and even by fostering social relationships. It’s a lot easier for neighbors to get to know each other when they’re walking down the same sidewalk than when they’re both racing to make the yellow light. And, however harrowing a fire may be, at least most of them are accidental and isolated. Measure HLA attempts to undo an entirely intentional, nationwide disaster.

The firefighters thus miss the city for the buildings.

It’s not the first time, though. Many cities’ street dimensions are already dictated by the size and performance of fire trucks. And, last year’s successful AB 835 made the case that fire codes that require most multistory buildings to include two stairways (for emergency egress) severely constrain the way residential buildings can be designed and, indirectly, make California cities uglier and more expensive than they’d be if buildings were allowed to have only one stairway.

I’m not an expert on emergency response. But I’ve been involved in urban planning long enough to know that, in too many instances to cite, the very people who are trained, paid, and empowered to design our cities somehow get shoved aside. Meanwhile, veneration for emergency responders — much of it well earned — has often given them, and their unions, unduly loud voices in the civic discussion.

Not this time, though.

What’s especially bonkers about the firefighters’ opposition to HLA is that they are almost alone. The list of groups that have endorsed it is not just long — it’s also among the most diverse you could ever imagine in Los Angeles. Plenty of other unions support it, including the SEIU and the teachers union. Elected officials have lined up in favor of it. Seemingly every mobility, environmental, and social justice organization has too. Democratic groups support it, and so does the Los Angeles County Business Federation. If ever a group could be expected to oppose a measure that de-emphasizes the use of cars, it would be the United Autoworkers — but, no, they’re on the list too.

For all of this enthusiasm, I’m not sure that the mobility plan will cure all that ails Los Angeles’s streets, even if it’s supercharged by Measure HLA. And I certainly don’t know if $3.1 billion — or whatever the true amount is — would be a sound investment. But, the fact that concepts once as obscure and forlorn as “complete streets” and “active transportation” are on the ballot in a famously car-centric city has to be good news, for planners and pedestrians alike. It has at least a chance of making the city safer and more attractive.

Of course, I don’t expect those billboards to come down any time soon, and we’re probably stuck with the freeways too. But we can at least hope that some of those attorneys go out of business.

You must be logged in to post a comment.