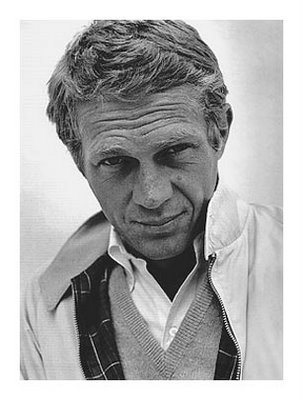

photo by Gilda Davidian

“Something to Live For”

A young man without direction idolizes an older man with money and a mysteriously tragic past.

a new short story by Andy Hurvitz

part 2 of the Billy Strayhorn trilogy

About, but not limited to, Van Nuys, CA.

photo by Gilda Davidian

“Something to Live For”

A young man without direction idolizes an older man with money and a mysteriously tragic past.

a new short story by Andy Hurvitz

part 2 of the Billy Strayhorn trilogy

Leland Lee Portrait, originally uploaded by Here in Van Nuys.

I was back in Palm Springs yesterday, planted like a palm tree amidst the gorgeous oddness of its windswept spotless streets, sitting at Starbucks amongst groups of people who looked as if they were from an elderly Mid-Western tribe.

On this day I was acting, as I always do when working, as a videographer. A writer friend had invited me along to assist him for an interview with 94-year-old Leland Lee, a photographer, who had shot the concrete space ship Elrod House in 1969.

The Elrod House, designed by John Lautner in 1968, is a home so iconic and so very weird. Like the latter part of the decade in which is what built, The Elrod is unhinged and sybaritic, self-absorbed and spacey, built for joy and sex and parties, featured in a James Bond movie and now on sale for $14 million.

Giant egos surely must have matched horns in the desert, 43 years ago, when architect and client carved and bulldozed the massive circular house onto a high mountain overlooking Palm Springs.

Architect and client are long dead, but living, still very much alive, is short, smart, stylish and self-effacing Leland Lee, who was only born in 1918, and achieved Mid-Century acclaim for assisting Julius Shulman in the photography of Los Angeles at its Post-War acme.

I have always hated the title “assistant”, having worn the dog collar myself, but here was an accomplished individual whose body of work burned up in a fire 10 years ago, but who still carries himself with a noble kindness and generosity.

Brown leather pants, a white linen jacket and printed silk shirt with a purple necklace, this was what he was wearing yesterday, and if clothing can give some indication of character, than Leland must be an eccentric, artistic, self-confident person, and that is how he introduced himself yesterday.

We drove up a long road and passed guards who ushered us into a cave-like driveway, and we entered the dark, soaring, circular living room where Leland’s framed photographs hung on the walls, and where we would film him as he spoke about each image.

What emerged from the interview was his quiet verisimilitude and the dignity of a gentleman who, without exaggeration and with calm exactitude, spoke about his photography and his life; his triumphs and his tragedies, with focus, clarity, deliberation and observation.

I was there, almost to witness and maybe to absorb a moral lesson of life, one that I have to teach myself continually, that non-conformity and truth, the willingness to be honest and to avoid grandiosity, those qualities that I think I have, will not always pay-off monetarily in the end. The 94-year-old cheerfully admitted he had never signed a contract before, and he didn’t seem to live for legal and financial judgment.

I have been battling, for many years now, between self-destruction and self-creation, wondering whether my own self-expression, in print and photo, was endangering my future. For surely Googling “Andy Hurvitz” might reveal the truth of who I was.

And then I met Leland Lee yesterday, and saw a man who had got on and survived, and did it in his own way, not always triumphantly, but truthfully.

The 20th Century died 11 years ago, and now some of my most beloved family from that epoch, are dying, fading off, and exiting. And I hardly had a chance to get acquainted.

Born two years after the Versailles Treaty ended WWI, before Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, before penicillin, direct dial telephone, credit cards, air-conditioning, television and the discovery of the planet Pluto, Harold Hurvitz (1921-2011) was the eldest of three born to Harry and Fanny Hurvitz, who were also the parents of Frances Cohen (1923) and my father Sol (1932-2009).

Harold’s life, biographically and chronologically, encompassed engineering, WWII, husband-hood and father-hood and the building of a successful, multi-generational heating and air-conditioning company that outfitted the many steel and glass buildings anchored low and towering high in the City of Big Shoulders.

Tall, blue-eyed, sharp, intelligent, and possessed of a calm fortitude and self-assurance befitting a man who knew his place in the world, Uncle Harold was for years the gold standard in our family for character, kindness and an inability to be disloyal.

He was married, in 1943, to a woman he had already known for perhaps a decade, (Aunt) Evey. They lived on the South Side, in those intact Jewish neighborhoods of apartment houses, synagogues, delis and social clubs. Those were the days, of Benny Goodman and Drexel Avenue, Hyde Park and Maxwell Street, of black cows and red meat, shvartzes and Chinamen, Inland Steel and the Outer Drive, the Union Stockyards, Soldier’s Field, Irv Kupcinet, the Chicago Daily News, Dad’s Root Beer and Jack Brickhouse.

After the war, Harold and Evey had three kids: Adrienne, Michael and Bruce, and these three went on, under the benevolent leadership and example of their father and mother, to create families of their own, made up of people who have mostly worked to build prosperity, build family connections and create a unity and purpose for life.

How I imagine I fit into my own family, and how my father imagined he fit into his family are curiously and strongly connected to the life of Harold Hurvitz.

I found, after my father died in 2009, that I was more cautious about the mythology of autobiography. A human being creates his own story, and he adheres to it, whether true or false. Let three children come out of the same womb, and each child will have his own version of family life and how well he was raised.

The death of Uncle Harold is strange, strange because his tenure on Earth was so long, and his presence, like the columns holding up the Parthenon: structural and eternal, resistant and real.

My own relationship to Uncle Harold was fashioned by the mythologies and stories filtered to me through my parents who thought Harold and Evey and their progeny had it made…..

They were going on a cruise. They were getting married. They just had a baby. Simi and Mickey, Evey and Harold, the two Mikes, the two Sues. It was a drum-roll of hearing about family through the stories of other people, rather than experiencing them yourself. And through many years, my father, in NJ, spoke on the phone with his brother through artful dissonance and polite chit-chat.

The good news that emanated from the golf course, from Rancho Mirage and Lake Shore Drive, from Deerfield and Highland Park….the stories that I heard, were stories of laughter and success, of camaraderie and closeness, procreation and prosperity illuminated by the floodlights of the Palmolive Building, orchestrated by a band playing in the Drake Hotel, for the majesty of a candlelit apartment in a high-rise, accompanied by many well wishers and lots of food.

In every photo: baby-faced boys and well-fed girls, golf courses and cruise ships, summer camp, yarmulkes, bar mitzvahs and bat mitzvahs, Water Tower Place and Frango Mints, Scottsdale, Boca Raton; Filet Mignon, and chopped liver; enormous platters of cold cuts on silver trays. This is how it seemed. And one never knew the tedious, back-breaking and time-consuming labor that built it all inside a windowless warehouse somewhere north of Touhy.

And sometimes the image of Harold’s family stood in opposition to the hard times we had in our smaller family of Sol. I had thought, maybe unfairly, that my own father minimized himself and aggrandized his older brother, to his own detriment. But my father relished his own artistic and independent streak. And he was not the first-born, but raised to idolize and respect and look up to the first- born.

My father had epilepsy, difficulty earning a living, back problems and a disabled child. And finally he succumbed, quite early, to a degenerative cerebral illness that robbed him of the ability to speak and walk. But if he were alive, he would tell me not to write any of this and just to remember that he was a good father and a good husband.

After my father died, I went out to Rancho Mirage and visited Uncle Harold, 11 years older than my father, but still alive and smiling. He was attached to his own plastic oxygen tube . And wheeled, by a home care aide, around a vaulted ceiling desert ranch house where he and Aunt Evey had spent thirty summers, and were now confined year around.

Uncle Harold said he was “an anomaly” because he had almost died earlier that year. He said he believed mostly in “blind dumb luck”.

And luckily, he was born a Jew, not in Poland or Germany, but Chicago; and luckily he met a woman he loved and stayed with for seven decades; and luckily he had great children who venerated and adored their father; and luckily he lived to see and touch and kiss grand-children and great-grandchildren.

And despite his time spent in the West, Harold, like my father Sol, was a Chicagoan, raised to think that if you just worked hard, thought logically, did the right thing, told the truth, you might just succeed.

He had absorbed the ethos of Chicago, a self-confident city of fighters and survivors, given to powerful winds and brutal snowstorms, blinding rain and suffocating summers, violent crime and astonishing wealth, yet boisterously productive, practical, energetic and hopeful.

Harold managed to endure and to leave to the rest of us, a lesson that success is not about mastering the latest technology, but by living according to those codes of honor that never die.

And family….above all… The Family. It stands supreme, and is there for those who are weak or falling down, and for those who are strong and on their way up, young and naïve, old and wise, middle-aged and stressed out. They all have a place in this family. And they must not forget that they are not alone.

My father died April 13, 2009.

Since that day, I have kept his wallet inside a white ceramic vase on a square table next to my bed.

To hold another person’s wallet, without their consent, even when they are dead, seems a violation.

And what possession is more personal than a wallet?

Like the expired man, his wallet contains expired credit cards.

I read the business cards stuffed into the wallet pockets.

One card is The Valley Hospital in Ridgewood, NJ where I saw him on the morning of October 14, 2006 after I flew into Newark on a red eye from LA. He had suffered some sort of a small stroke. And I cried at his bedside.

A Department of Veterans Affairs ID, created only a few months before he died.

A card from a Speech Pathologist who would help him pronounce words at age 75 that he once could say without practice.

He was a painter and took art lessons at The Ridgewood Art Institute. A green paper card, frayed at the edges, was valid through August 31, 2007.

AARP, Medicare, Costco, American Express, AAA, Master Card and Visa: the cards of a modern living American male. Pieces of plastic to insure, to protect, to provide, to make credit for any activity on Earth.

In his last week of life, I remember he was breathing with difficulty as he sat on a bar stool bench, at the kitchen counter in his apartment, going over his taxes, which were due in mid-April.

He was fatally and incurably ill and knew he would die from this inexplicable illness called Multi-System Atrophy.

But he was no different than any of us in his belief that he would continue to live.

My father’s wallet still seems to belong to a living person. And no amount of time or loss can diminish it.

LOS ANGELES (AP) — William Claxton, a celebrated photographer who worked with such entertainers as Bob Dylan and Frank Sinatra and who helped establish the organization that runs the Grammy Awards, has died. He was 80.

“Claxton died Saturday at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles of complications stemming from congestive heart failure, his son Christopher said.

He was best known for his soulful portraits of jazz artists such as Chet Baker, and he went on to photograph Dylan and other musicians such as Joni Mitchell and Tom Jones. His images graced the covers of numerous albums.

Claxton, a founding member of The Recording Academy, started his photography career in 1952 while a student at University of California, Los Angeles.

He also worked with Sinatra, Steve McQueen and Rebecca De Mornay, and his photographs regularly appeared in such magazines as Life, Paris Match and Vogue.

In the 1960s, Claxton collaborated with his wife, fashion model Peggy Moffitt, to create a collection of iconic images featuring Rudi Gernreich’s fashion designs.

A film he directed from that era, “Basic Black,” is considered by many to be the first “fashion video” and is now part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Claxton also wrote 13 books and held dozens of exhibitions of his work around the world.

In 2003, he won the Lucie award for music photography at the International Photography Awards.

“He was a great photographer and a wonderful man who touched the lives of his friends through his generosity, charm and kindness,” said his publisher Benedikt Taschen, founder and owner of Taschen Publishing, in a statement. “Bill was very close to my heart and a pillar of our publishing house.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.