After a long hiatus, we ventured Sunday morning down to Culver City to walk around the new buildings and the architectural oddities.

Once a stronghold of flat, inland dullness, a largely white town peppered in a monotony of starter ranches and stucco apartments, barber shops, taco stands, model trains, gun stores, and typewriter repair shops, Culver City has undergone a two-decade long makeover into a town of light rail, bike and bus lanes, restaurants, lofts, luxury restaurants, furniture, art displays and wine bars.

29 is the median age for work, and 69 is the median age for owning a house. And everyone else of any age is welcome as long as you wear yoga pants and carry a small dog.

In the last two years, all the formerly open parking lots near the Expo Line have been filled in with large, modern architecture: residential and commercial.

The Helms Bakery area used to be the only area that imitated urbanity, but today we walked through it, and there were few pedestrians. But all the old furniture stores were open, and Father’s Office was getting ready for service. An electric bike was parked outside of the Kohler Store, a man and a woman conversed next to a fountain, and through my camera’s viewfinder 1930s Hollywood was alighted in 2022.

Washington Bl. is now a multi-use roadway with specific lanes for cars, buses, bikes and pedestrians, an oddity of our region that takes some mental and focal readjustment.

A thin, blond woman in mask carried a shopping bag and waited for the light to change near Shanti Hot Yoga (“We’re open again! 7 Days of Yoga for $7”).

On the corner of Washington and National, adjacent to the elevated rail, there were new buildings, each one different but not too different: modernism with steel, glass, angles, some wood and some plants, and strong, assertive street walls.

On National Blvd with its spotless sidewalks and young trees, we walked, tranquilized and medicated, by train sounds and light breezes. A paved bike path coexisted with a train that hummed down the tracks high up on a concrete overpass.

Sunshine was rampant and inescapable.

We were the only pedestrians.

I had that disembodied sensation one only finds in Los Angeles: isolation and excitement, boredom and anticipation, urban exploration in a landscape of sunshine and emptiness.

At “Nike Corp – Extention Lab”, 3520 Schaefer St. steel girders and compressed lumber presented an incomplete cathedral of construction. The wood was blond and warm. The materials seemed ready to be pounced on by that shoe brand’s rubber sneakers.

We walked south one block to Hayden Avenue, to a junction of ugly brilliance: Samataur by Eric Owen Moss, the architect whose offices and deconstructed designs decorate the entire street.

Before the pandemic I would have hated this discordant scene, but now I rejoiced, for the chained off tower and the accompanying office blocks survived intact: startling, grotesque; yet unique in their ambitious awfulness: empty parking lots, cinderblock walls, dark glass windows.

And a sign called “Clutter.” Without any.

These are the workhouses for young, multi-cultural creatives of dazzling imaginations whose languages are only taught at MIT or art colleges. I’m sure these well-compensated bees have worked on my brain many times as I play video games or buy a bottle of gin with the most gorgeous and award-winning fonts, or scroll through Netflix. They are all 29, tall, and play frisbee on the roof and bring their dogs to walk and I really do hate them all.

They work for companies where Tyler, Dylan, Ashley and Rebecca, must list their preferred pronouns after their names and every company has a mission statement that begins with “we believe every human being has the right to…”

On the west side of Hayden, 3535 is another Eric Owen Moss, a multi-story stucco structure from 1997 with protruding supports that fly out of the building, angled walls angled for entertainment. Everything is decorative irony, not form follows function, but form for forms sake. Tenants are graphic design and media companies. This is a perfect setting for sons-of-bitches startups, Tesla influencers, wellness lubricants, Armani jackets and collectible sneakers.

At 3585 was Sidlee. This conglomeration was perhaps the most interesting of all the oddities along Hayden Avenue.

The company, which describes itself in the most inscrutable and amorphous ways[1] has seemingly vacated this arrangement of forms and textures scattered along a parking lot like a museum of sculptures.

Vespertine, (dinner for two: $650) a luxury restaurant of museum like dishes, was the tenant of a tall glass building encased in protruding, undulating sheets of horizontal and vertical steel. It was built next to a river of concrete rocks like a dry stream; nearby, a four-story tall steel tower sculpture supported rows of steel cactuses in steel pots suspended 40 feet in the air; a concrete park was furnished with cushy concrete seats and shaded by shaved down cats tails.

If the ghosts of director Michelangelo Antonioni, and actors Monica Vitti, and her still living co-star Alain Delon came to film a sequel to “L’Ecclisse” (1962) this would be their location.

Another strange fact of 2022 was the absence of security guards. I could walk up to any building and take photos. This was impossible from exactly September 22, 2001 to March 20, 2020, when Fear of Arab Terror was replaced by Fear of Invisible Virus.

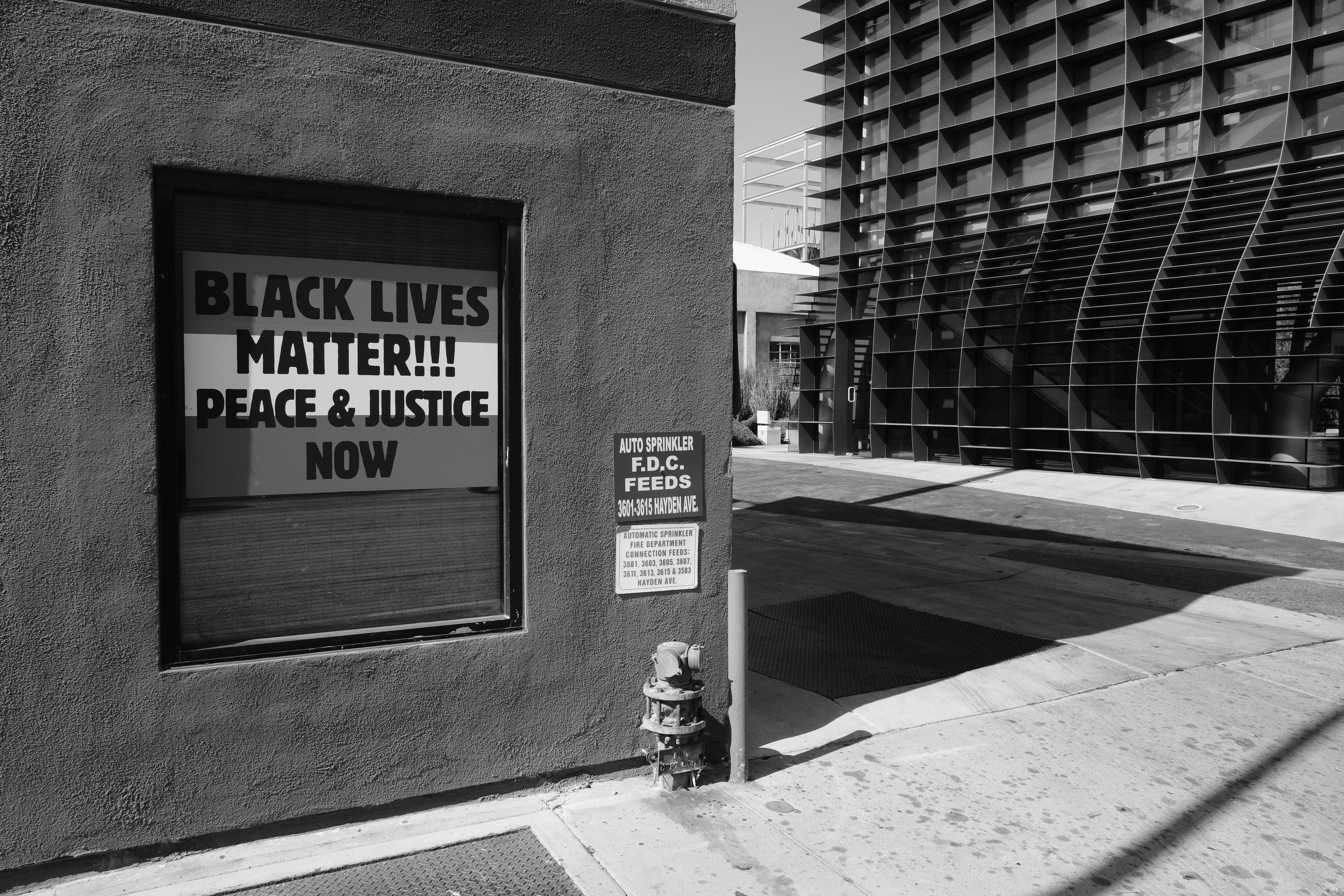

There were signs everywhere for masks and Black Lives Matter, and everywhere I looked I knew I was living in the here and now of 2022, poised somewhere between the past and the present, never quite certain of reality, but walking in it every step of the way.

END

[1] “Deep-rooted in the United States since 2012, Sid Lee Los Angeles has become a thought-leading hot shop for the country’s most iconic brands. With an extensive network reaching all the way to New York, our L.A. team delivers work that matters for a global clientele. This multi-faceted team at the epicenter of content and innovation offers fully integrated solutions supported by the weight of Sid Lee’s global collective.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.