________________________________________________________________________

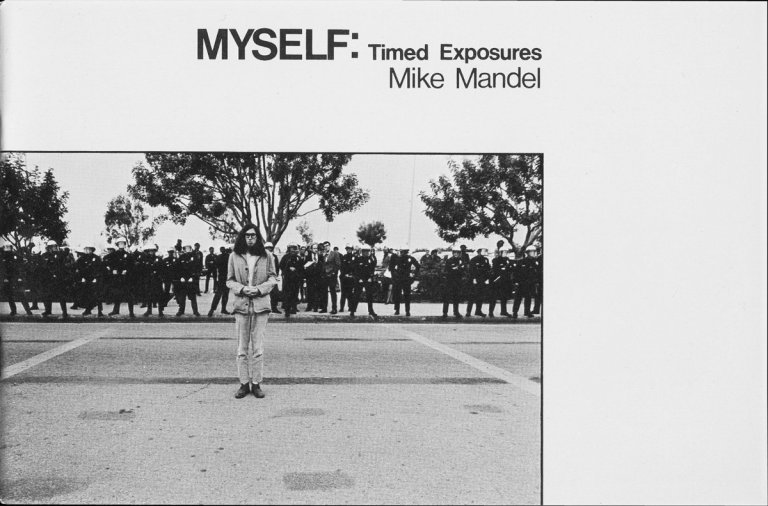

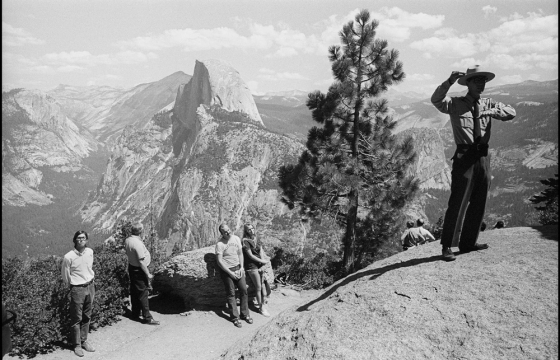

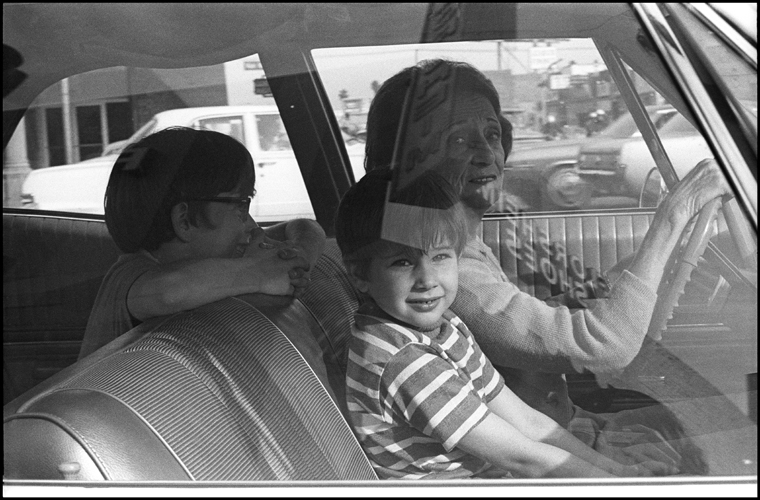

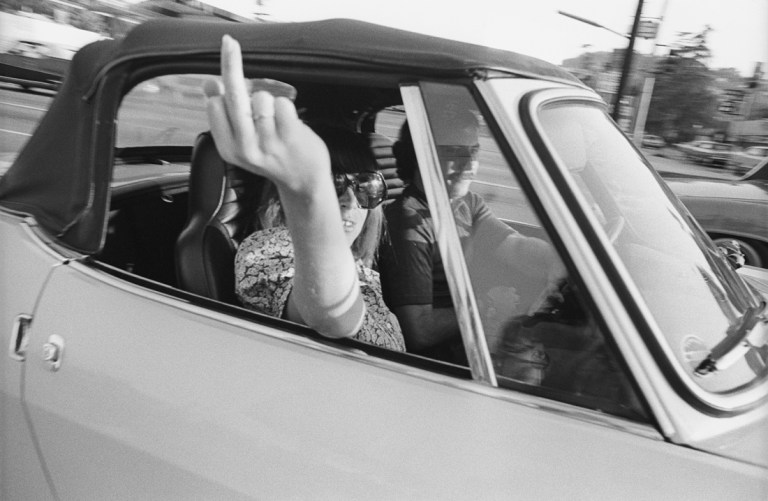

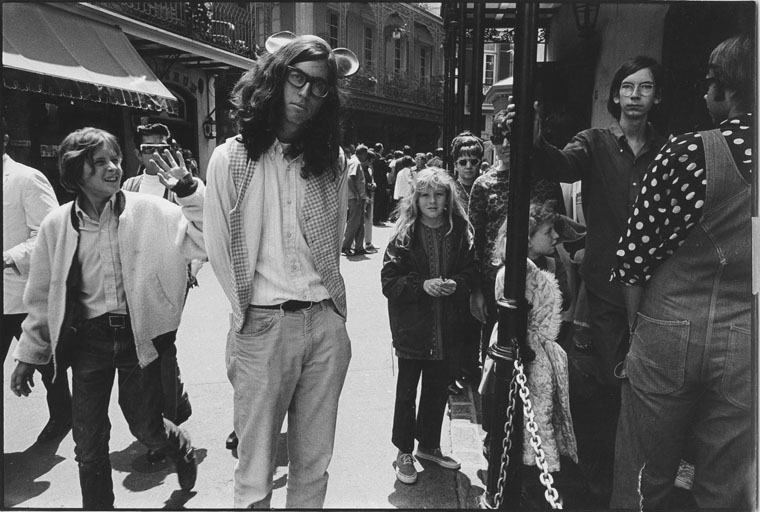

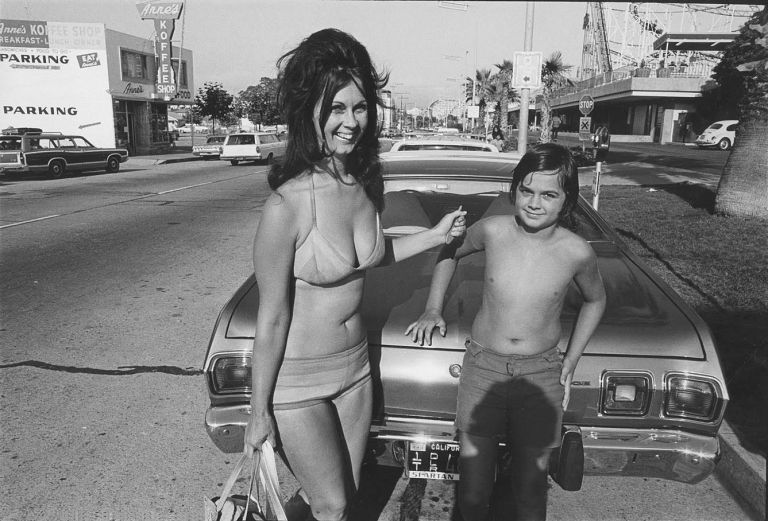

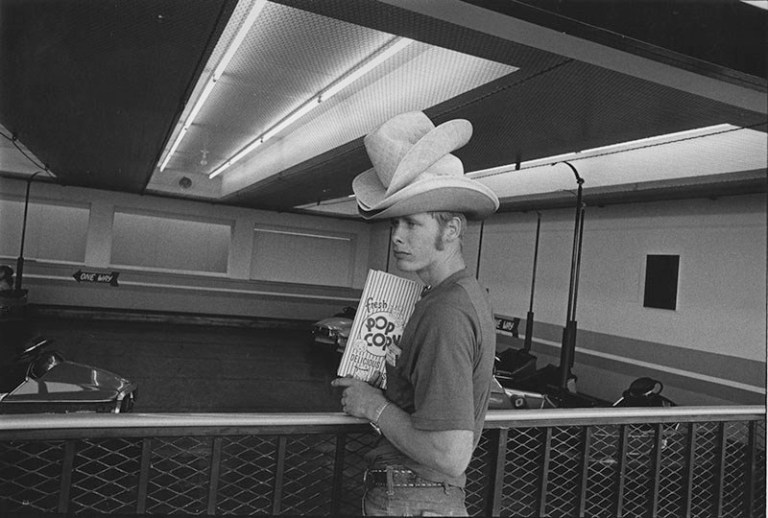

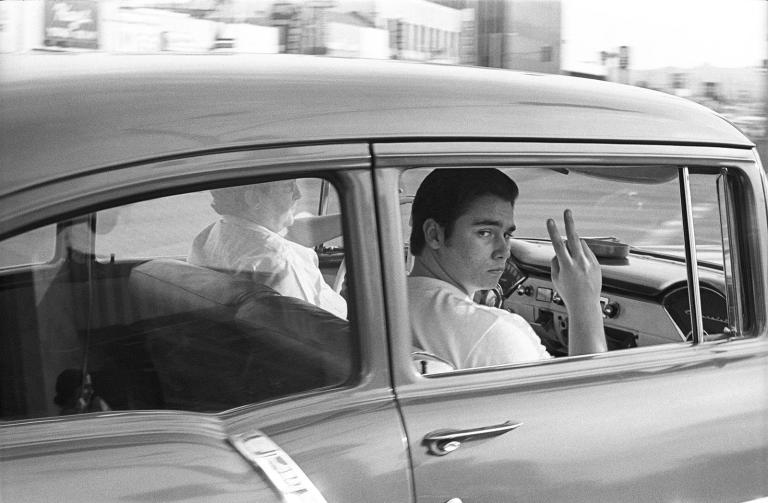

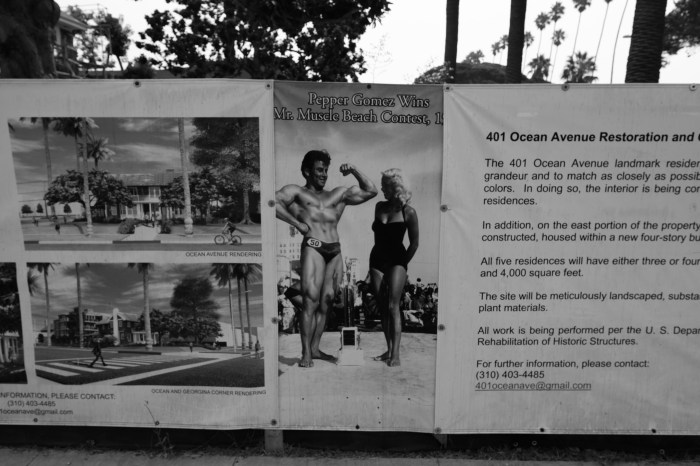

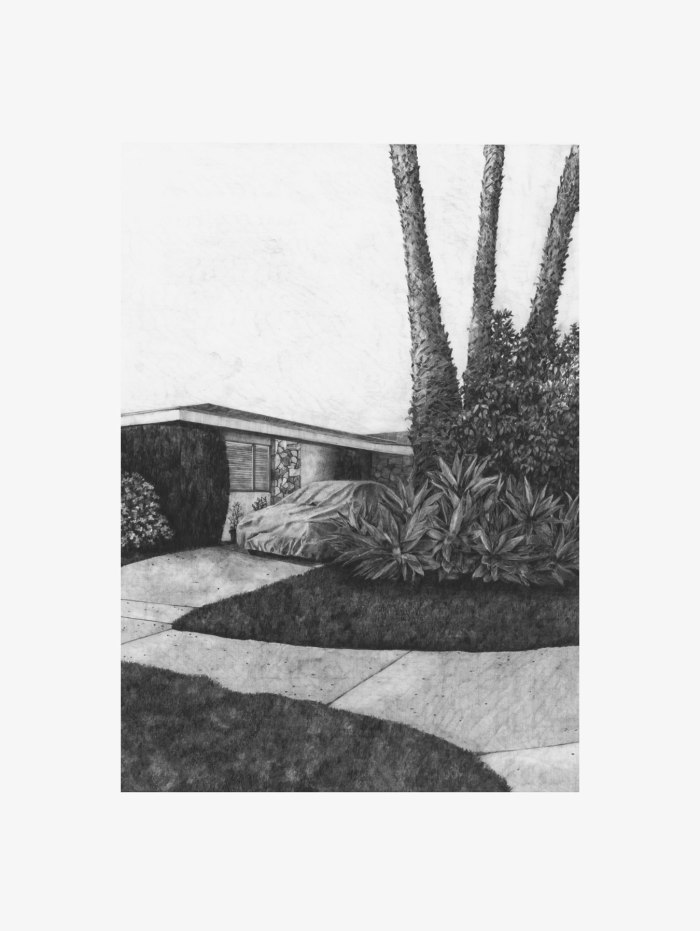

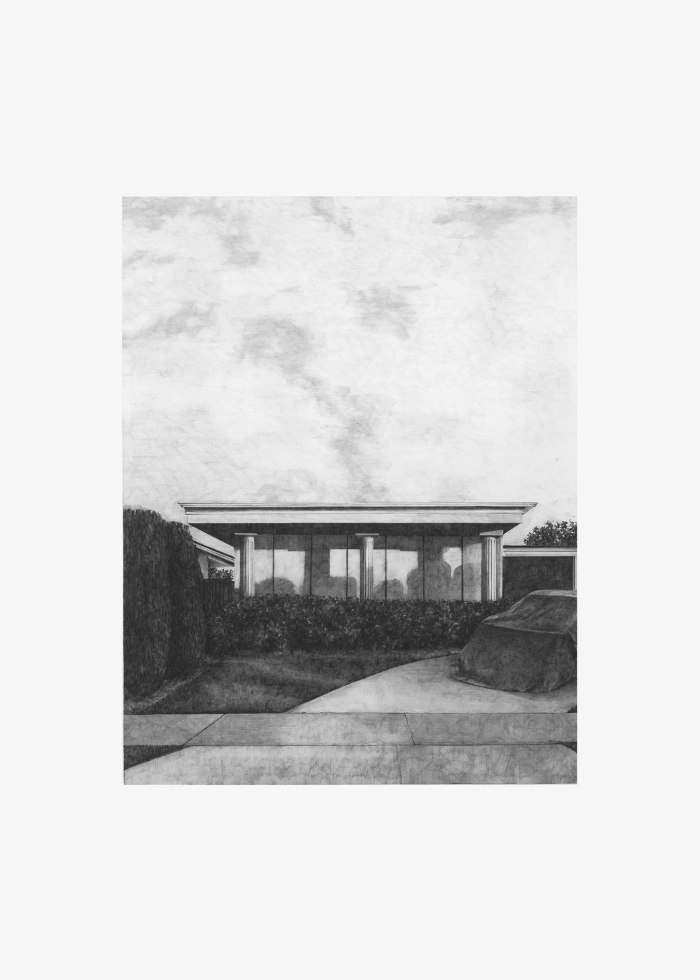

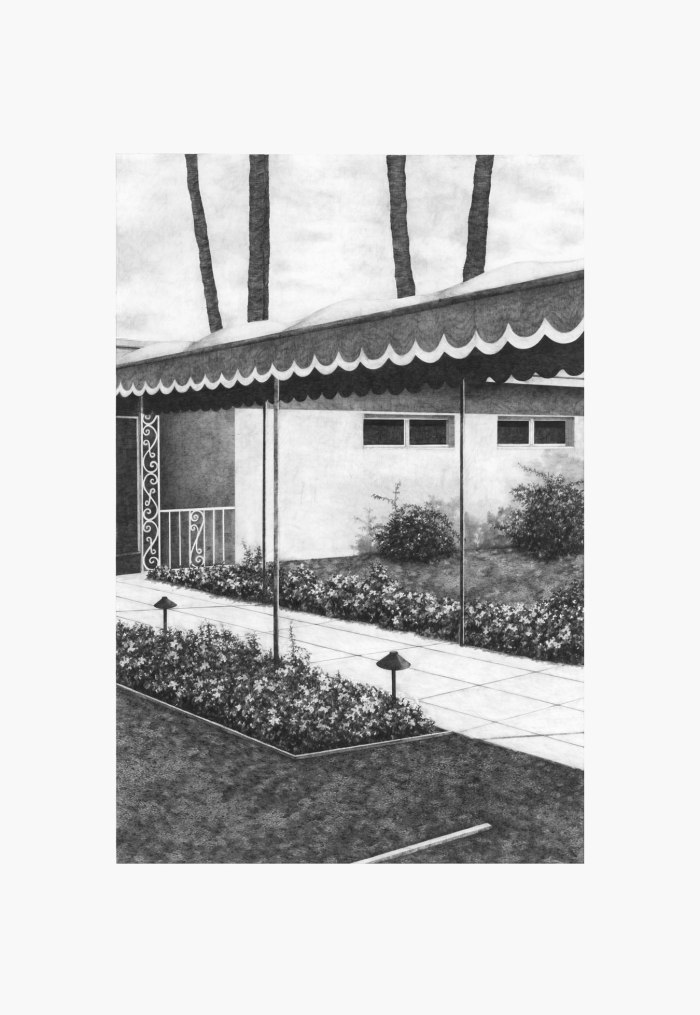

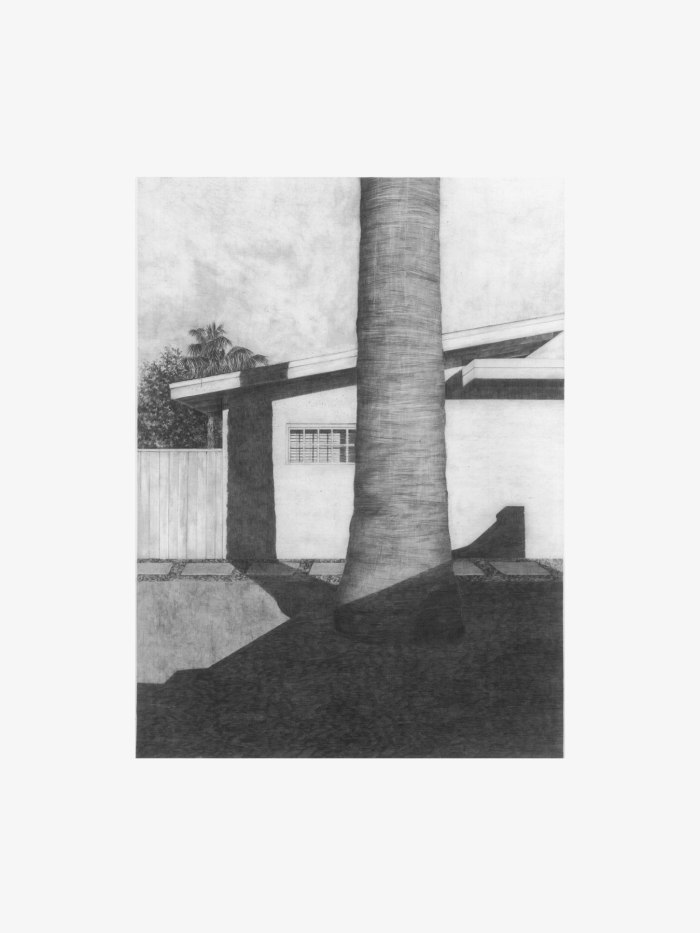

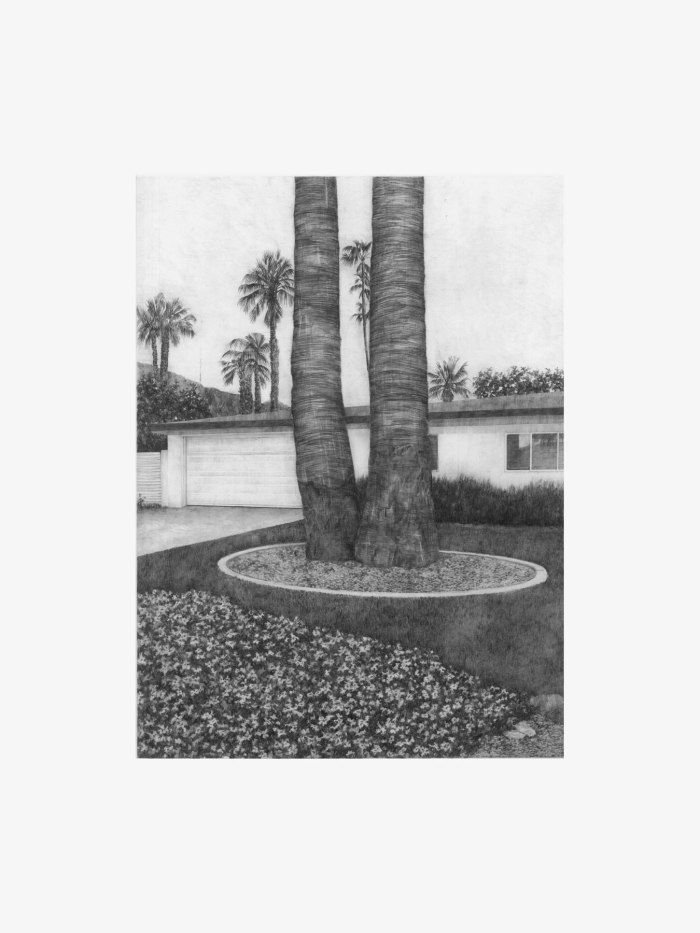

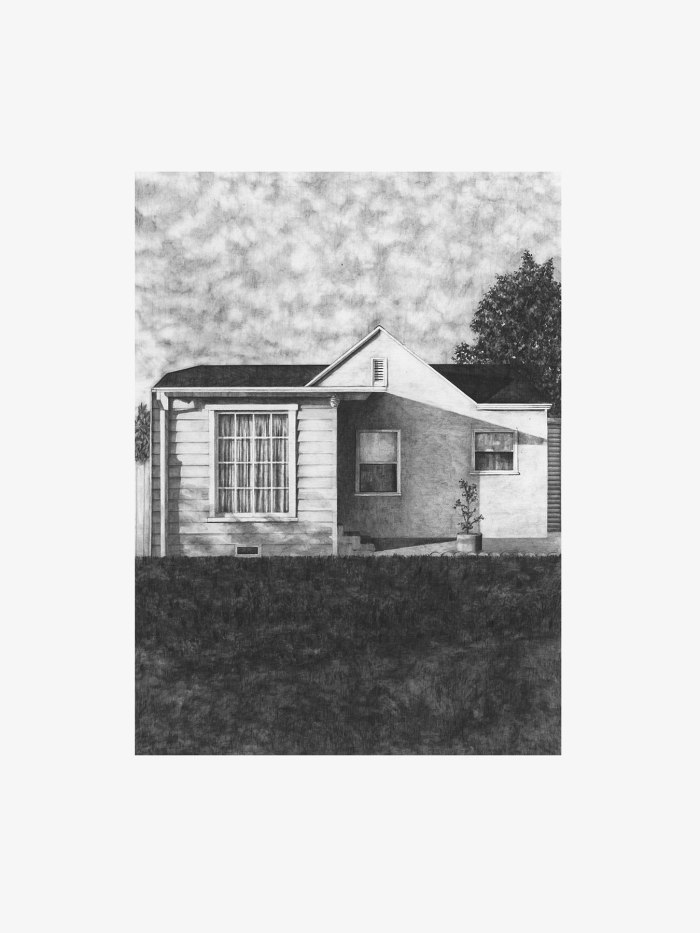

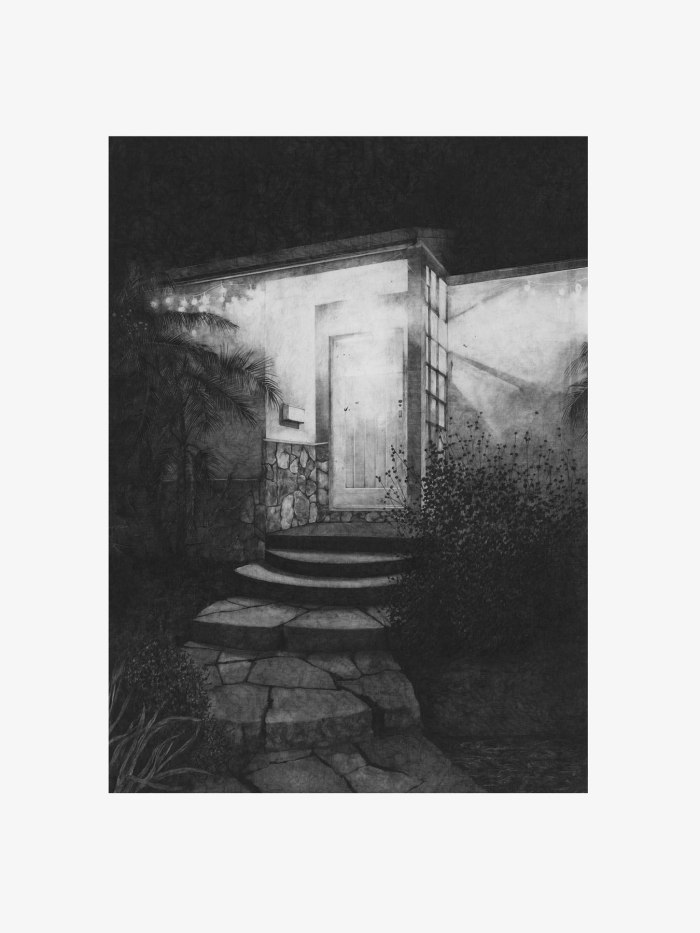

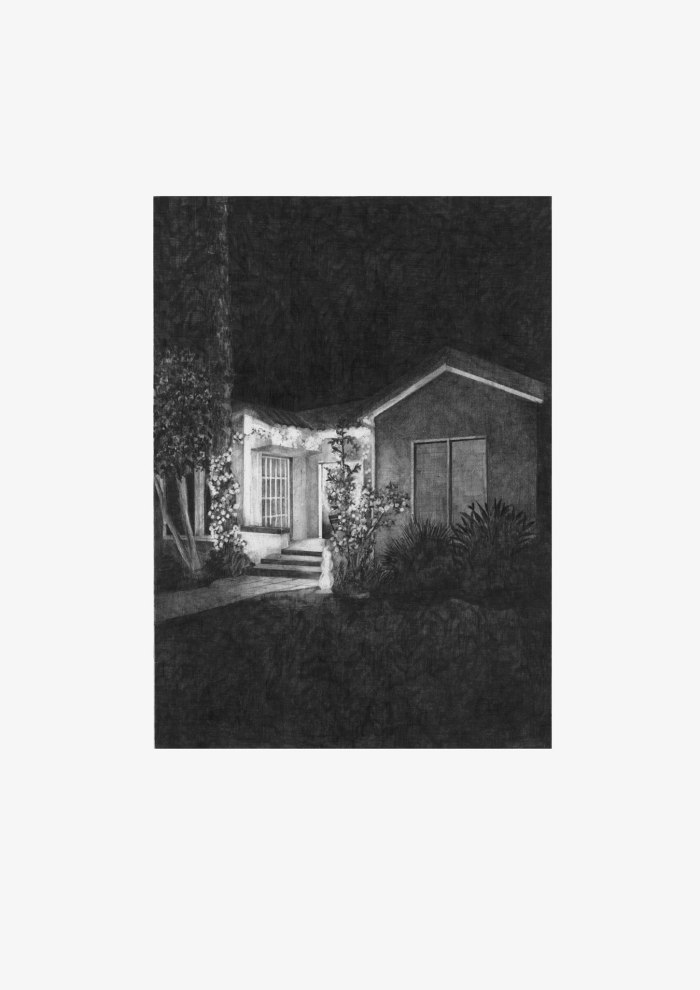

The New Yorker has a photo essay about Mike Mandel, who was born in 1950, studied at CSUN, and made a large body of photography here in the 1970s.

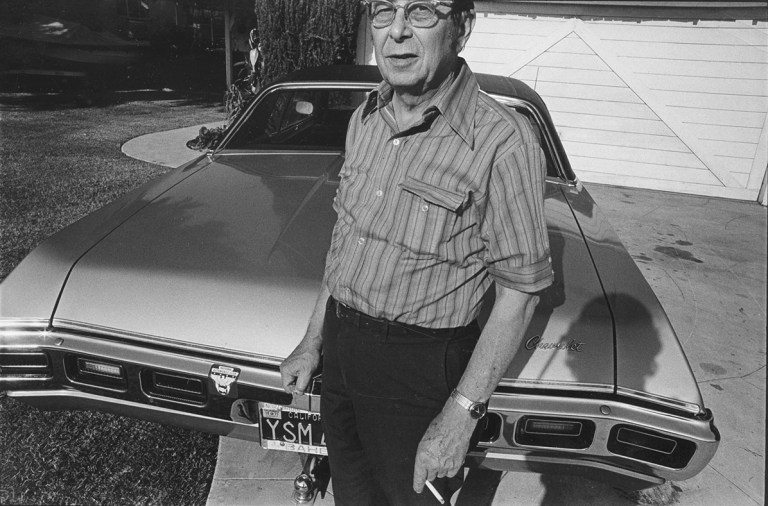

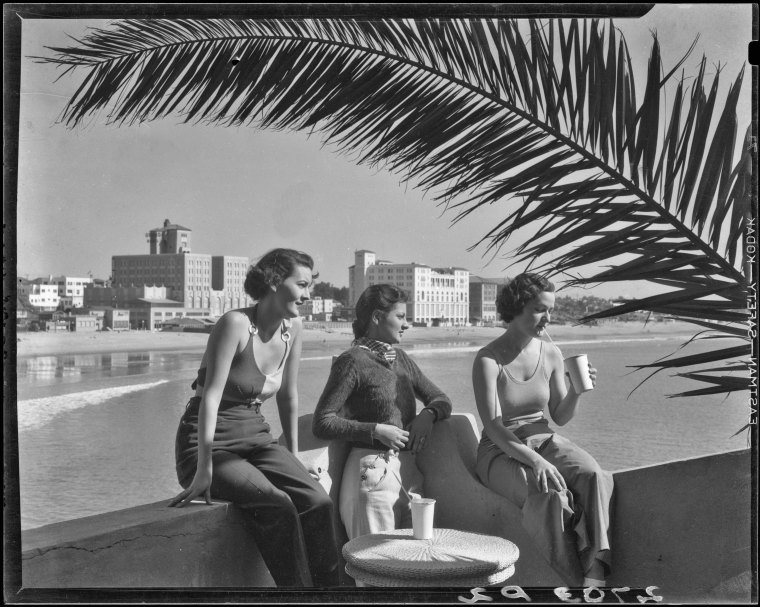

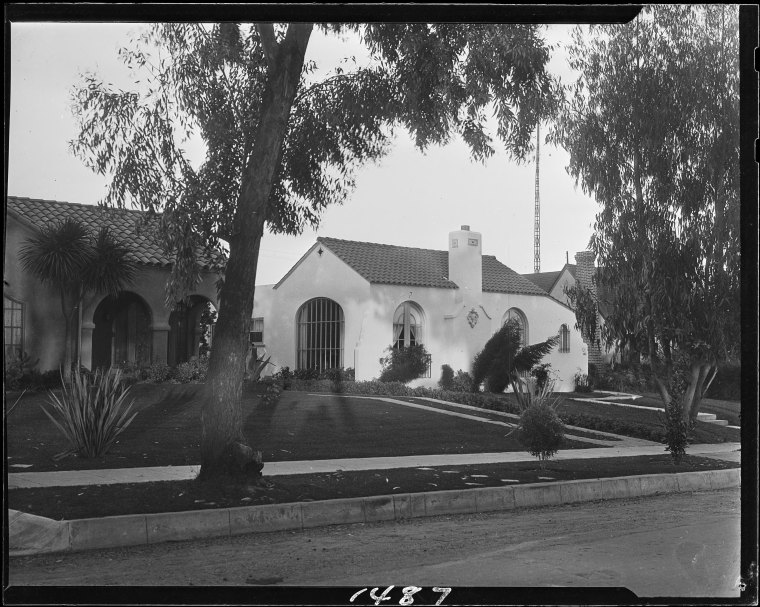

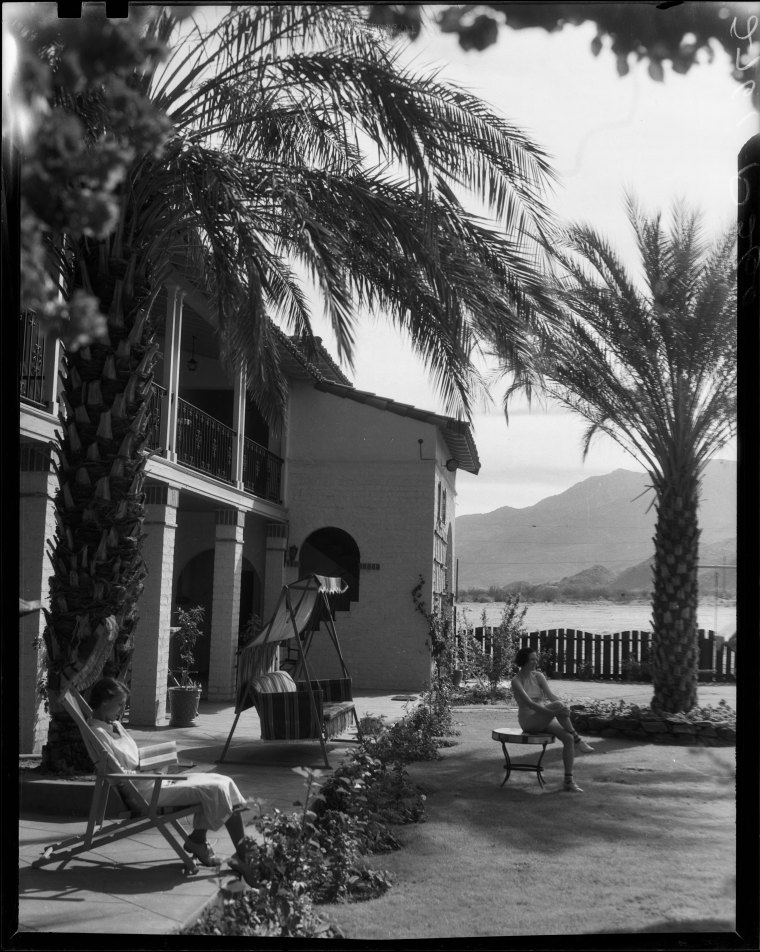

His work reminds me of the people who grew up here during that time, kids who were lucky to live a good life in houses with swimming pools, competent neighborhood schools, low cost college, and the ability to just do nothing, or everything, on foot, on bike, in car. Some are alive today, living in Encino or Woodland Hills or Studio City, inheritors of $2 million houses with $780 a year property taxes. These photos are their youth.

They had a rollicking good time in the past 70 years: getting high, going to concerts, having lots of sex, traveling everywhere and coming back to a freeway and shopping center universe in a city where only making yourself happy was considered the most profound errand in life.

The late 60s and early 70s was a subversive time with the Vietnam War, racial protests, and the Generation Gap. Anyone under 30 was thought angelic and gifted with great insights into human nature. Anyone over 30 was held responsible for all the hypocrisies and injustices of society. The Baby Boomers blamed their parents for conformity, environmental ruin, war and segregation. Yet these pissed off kids truly enjoyed a lucky period in the world, partaking of all the freedoms and leaving the bill for future generations.

The late 60s and early 70s imitated the time we live in now with cooler temperatures, unfiltered cigarettes and the insulted assurance that this country and state worked well for white people, and if everyone just got down, baby, and spoke their, like, mind, why, hey man, there was nothing that couldn’t be achieved, like even landing on the moon or dating Jane Fonda.

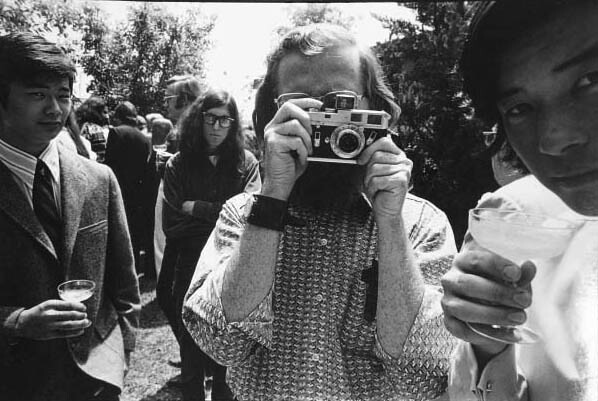

In the arts it was a time of blunt honesty, just showing things as they were, in music, movies and photography. There was group therapy, of just saying what was on your mind, no matter how embarrassing or crude or cruel. “Bob, Carol, Ted & Alice” captured that quintessential Southern California moment with its wry satire and takedown of the sexual revolution within married couples.

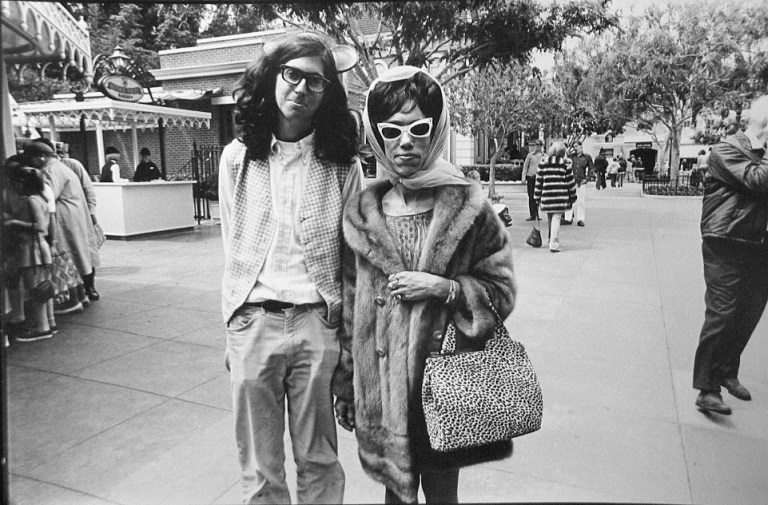

But there is nothing malicious or mean in Mandel’s work. It’s childlike in its openness, sweetness and curiosity.

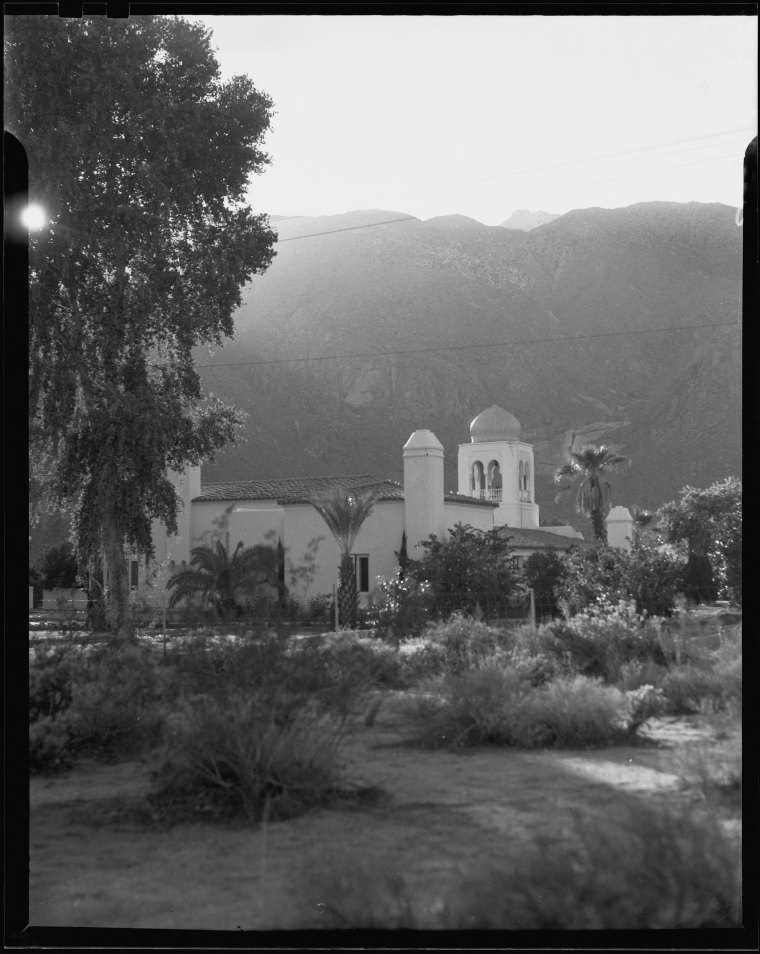

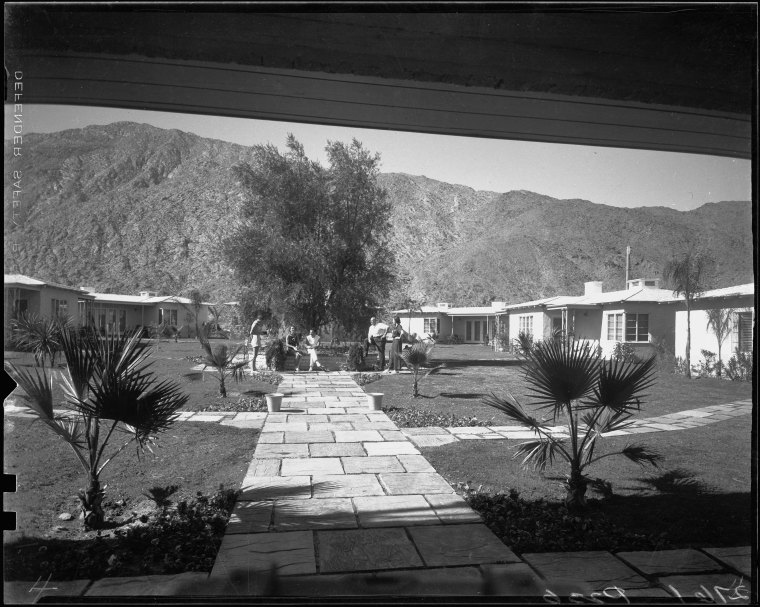

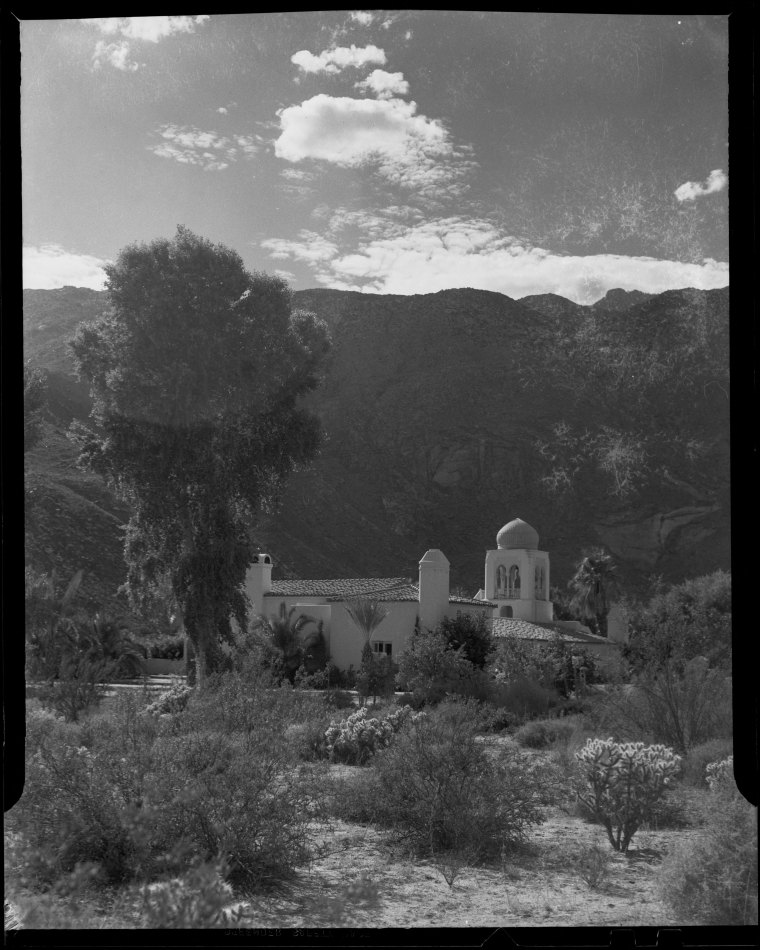

If you had a camera, and practiced photography professionally, you went out and shot photos of suburbia, of people driving in cars, or you were goofy and put yourself, like Mike Mandel, in the middle of the photo with strangers. You saw the humor in ridiculous juxtapositions of people and environment: the shirtless slab of guy in the butcher shop, the suede coated beauty next to the space laser game, the old lady on her driveway with her boat and garbage can, the double cowboy hatted dude with a box of popcorn next to the bumper cars.

Now these images are a historical record of a lost time. And we value their freedoms, dearly, as we endure temporary incarceration and social isolation during this pandemic.

You must be logged in to post a comment.