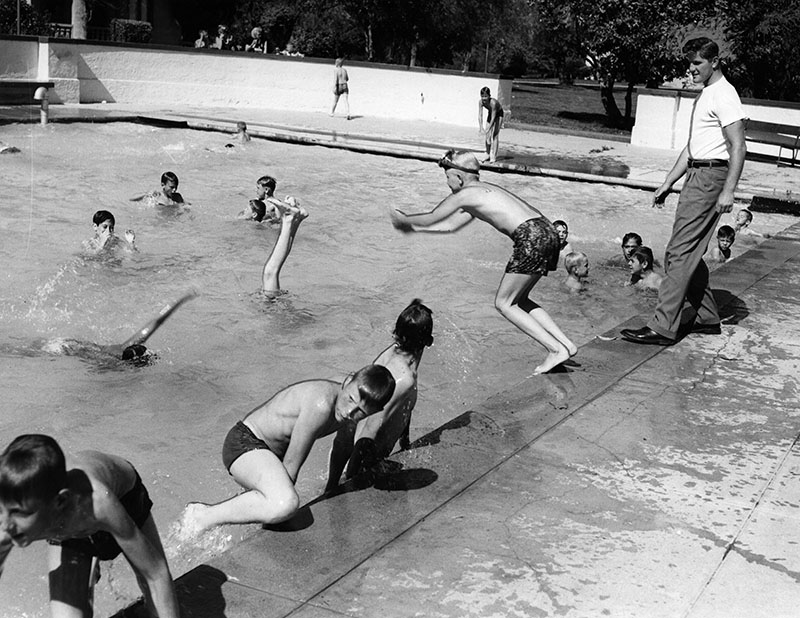

I once wrote about The McKinley Home for Boys (1920-1960) which stood on the present day land of Fashion Square in Sherman Oaks. It was torn down when the Ventura Freeway plowed through.The powers that be (bankers, developers, councilmen) decreed a shopping center to be the the only economically viable usage for that land.

What we have now, is a martian landscape of disconnected large buildings which themselves are nearing the end of their life form. The shopping mall is a fading attraction, but what might replace it?

At Riverside and Hazeltine there is an enormous project to excavate the property around the former Sunkist office building, an early 1970s brutalist structure that swam in a sea of asphalt and whose redeeming qualities were fully grown fir trees which have now been completely wiped off the landscape. The name “Sunkist” was a cruel joke referring to orange groves in the San Fernando Valley that were long ago destroyed. The inverted pyramidal office will remain in the heart of the new apartment community, now renamed “Citrus Commons” and again, real estate wins, and the community loses, except to get more “luxury” units nobody without parental inheritance or assistance can afford.

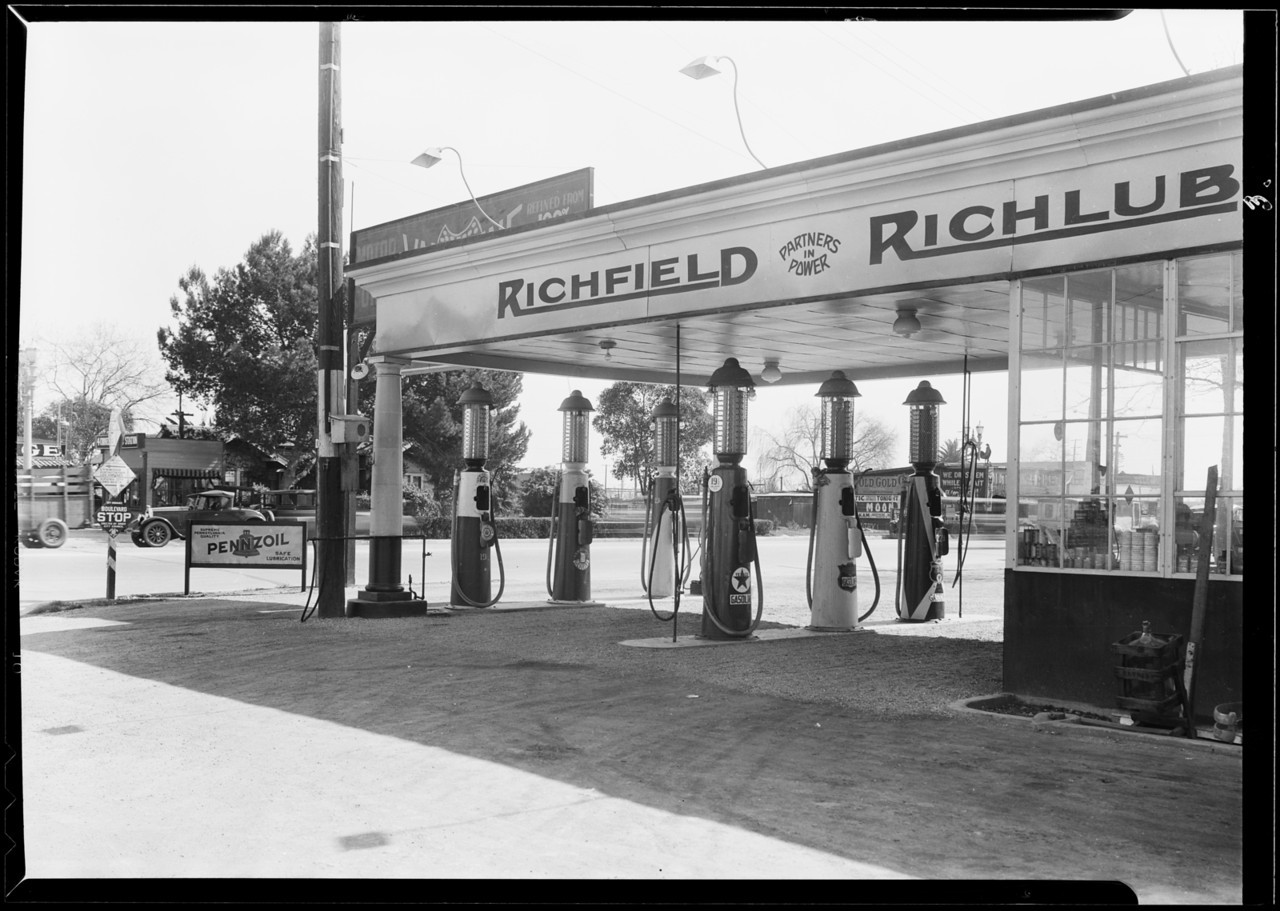

In the archives of the USC Libraries are these remarkable 1932 black and white photographs of the intersection of Riverside and Woodman when they were just rural roads in the middle of ranch lands. To the right of one of the images are benches and what might be the playing fields for The McKinley Home for Boys. Photographer was Dick Whittington.

The air was clean. Traffic was non-existent. The landscape was a tabula rasa for dreamers.

What do we have today, 90 years later?

The corner of Riverside and Woodman is four corners of disconnected “architecture.”

The NW is a late 1960s office tower in gold panels with an adjoining parking lot. Each floor of the sealed windows, mid-century “skyscraper” has unusable balconies, unaccessible from any office, just protruding forms signifying nothing, a decorative embellishment to make the tower fancier.

NE is the Spanish colonial high school Notre Dame with its good looking students from good families and good homes destined for good jobs and good colleges and good times.

SW is the ugliest shopping center in the San Fernando Valley with a covering of asphalt, outdated giraffe light posts on concrete posts, and a smattering of cheap and unnecessary stores: Bank of America, Pet Smart, Sports Authority and Ross. A parade of oversized vehicles with tinted windows and distracted drivers, and oversized people in black leggings; shoplifters, bank robbers, angry women, vapers and hucksters, actors and influencers, aggrieved SUVs, nearly deceased elderly drivers; pours in and out, all day, in the 100 degree heat, honking and pushing their way into a parking space.

SE is a 76 gas station, the kind that always has the highest per gallon price in the city, and several large billboards.

Everything else at this intersection is all about getting on or off the 101 freeway. Nobody would walk here willingly: burned by the sun, threatened by speeding cars, buffeted by air pollution and visual discordance.

What would this area look like if there had been a plan put in place for development with coherent architecture, walkable streets, trees, etc? Why do we think that mediocrity, ugliness, and environmental destruction are the best we can hope for?

You must be logged in to post a comment.