Returning from Pasadena last Sunday, we crossed into Highland Park and randomly drove up N Avenue 66, a street along the Arroyo.

There were old houses, once gracious houses, that a century or more ago were single family residences with wide gardens and porches and plantings. Most had been disfigured and broken up into rooming houses or torn down for crappy apartments in the 1950s.

Climbing into the hills we entered into another sub-district of mid-century ranches on small plots on curving streets, one, perhaps jokingly named Easy Street.

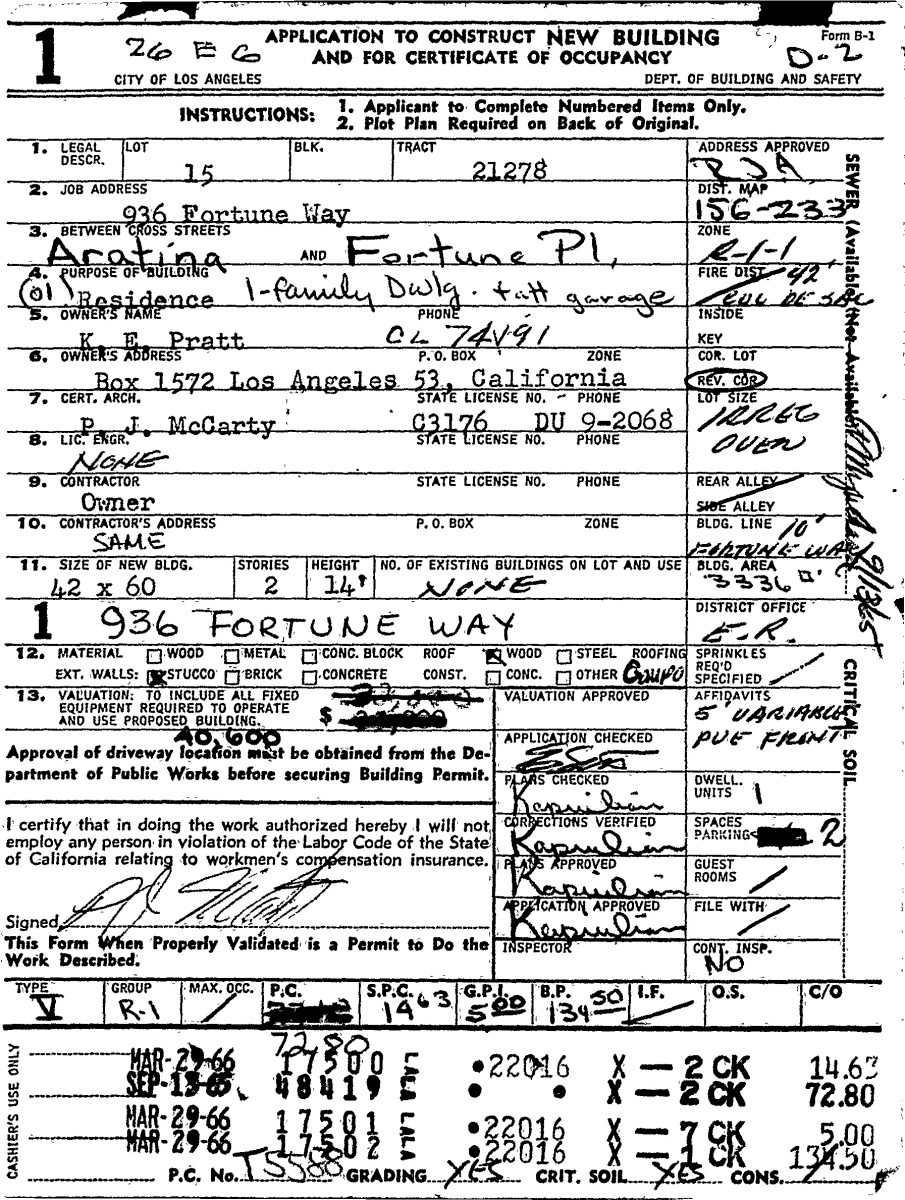

Then we stopped to admire 936 Fortune Way, a 1966 home built for $40,600 by architect PJ McCarty.

A box on concrete blocks with decorative panels and metal screens, it has a large, flat roofed portico supported by two tall steel posts with hanging globe light, concrete steps and a second floor balcony shaded by the overhanging roof and privacy screens along the rail.

Though there are palms and desert plants implanted into the blocks, the overall effect of the surroundings of the home is one of deadness in the hot, blinding, relentless sun; lifeless streets without pedestrians, enormously wide for maneuvering and parking enormous vehicles; and the strange, atomized artificiality of suburban numbness, a place where the people are inside in darkness and air-conditioning, on digital devices, high, drunk or napping.

Trained by media to desire and salivate for now unaffordable homes like this one, we don’t often think how very weird and self-destructive LA is, where multi-million dollar houses can exist without anywhere nearby to walk to, without any sense of community, only a coming together to fight crime or development, actions which make people feel better without accomplishing anything significant, lasting or beneficial.

You must be logged in to post a comment.