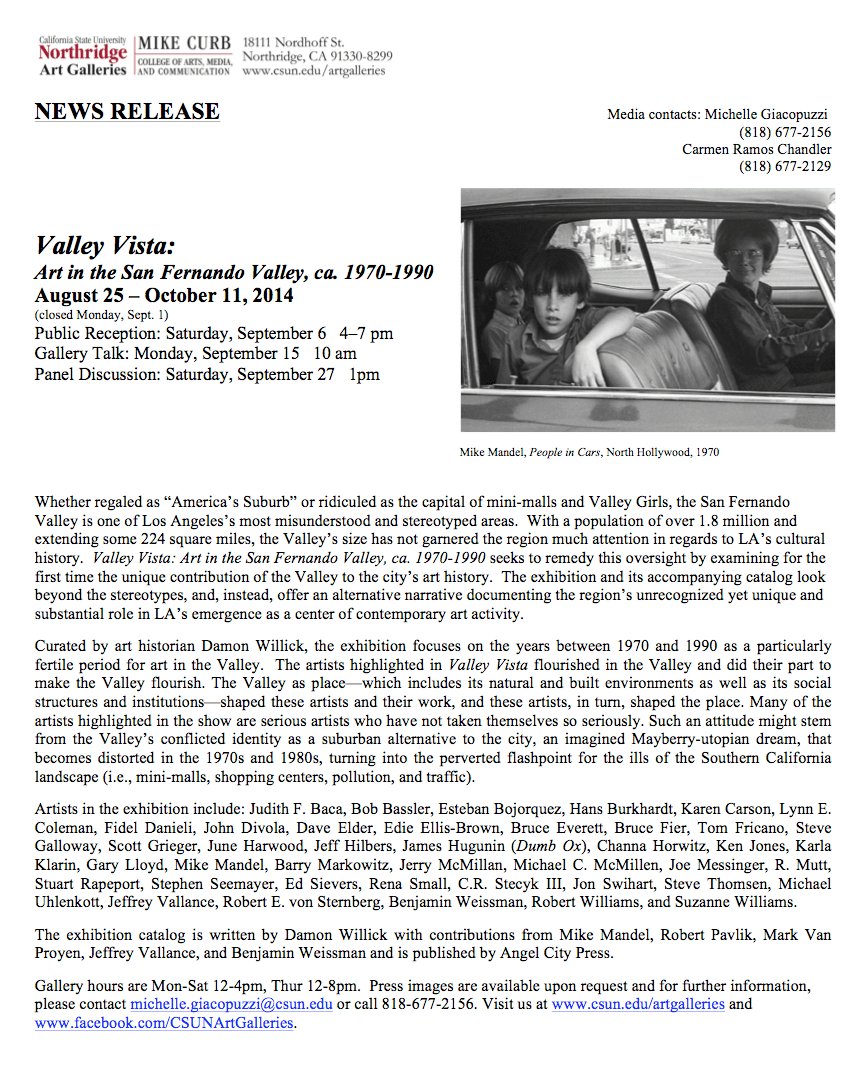

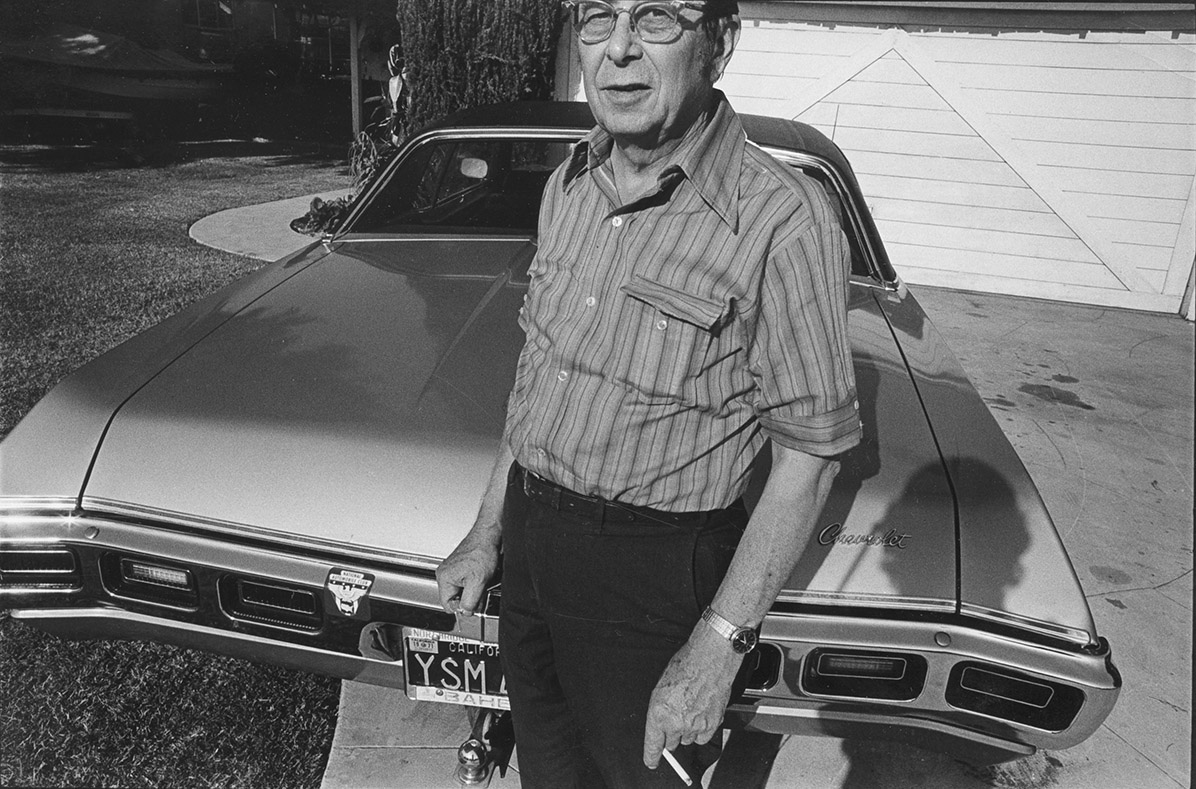

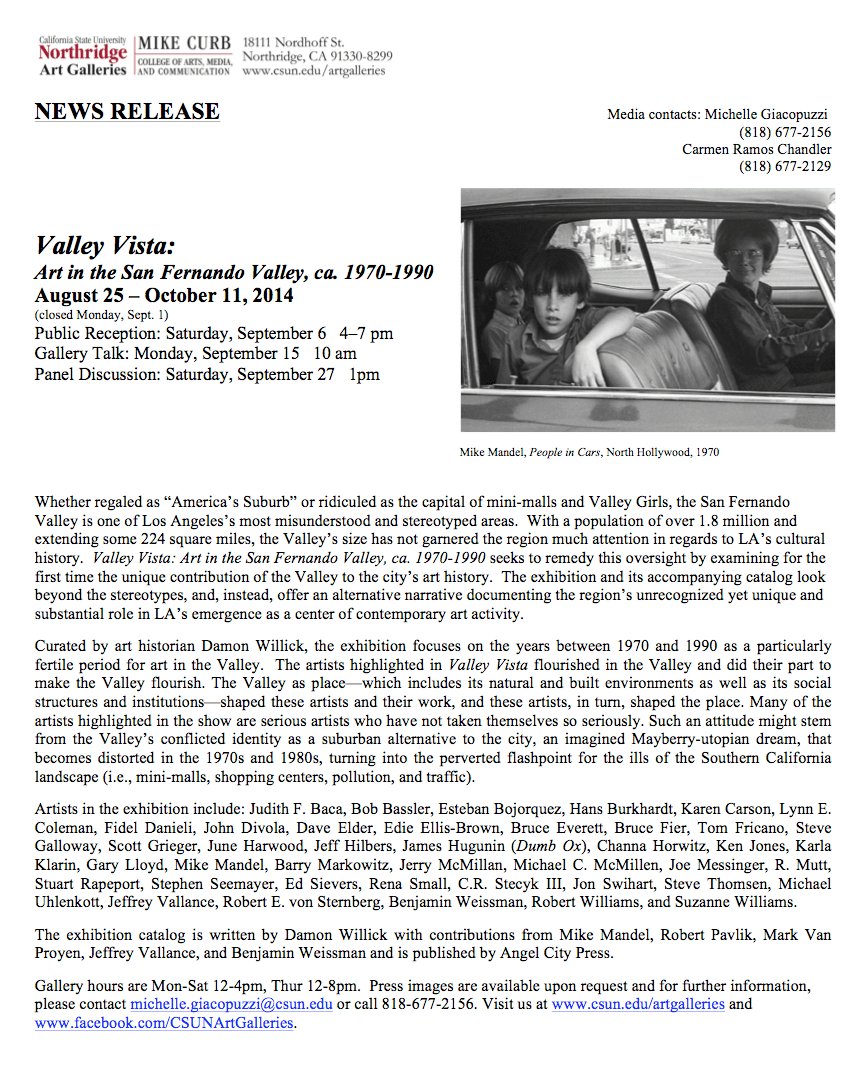

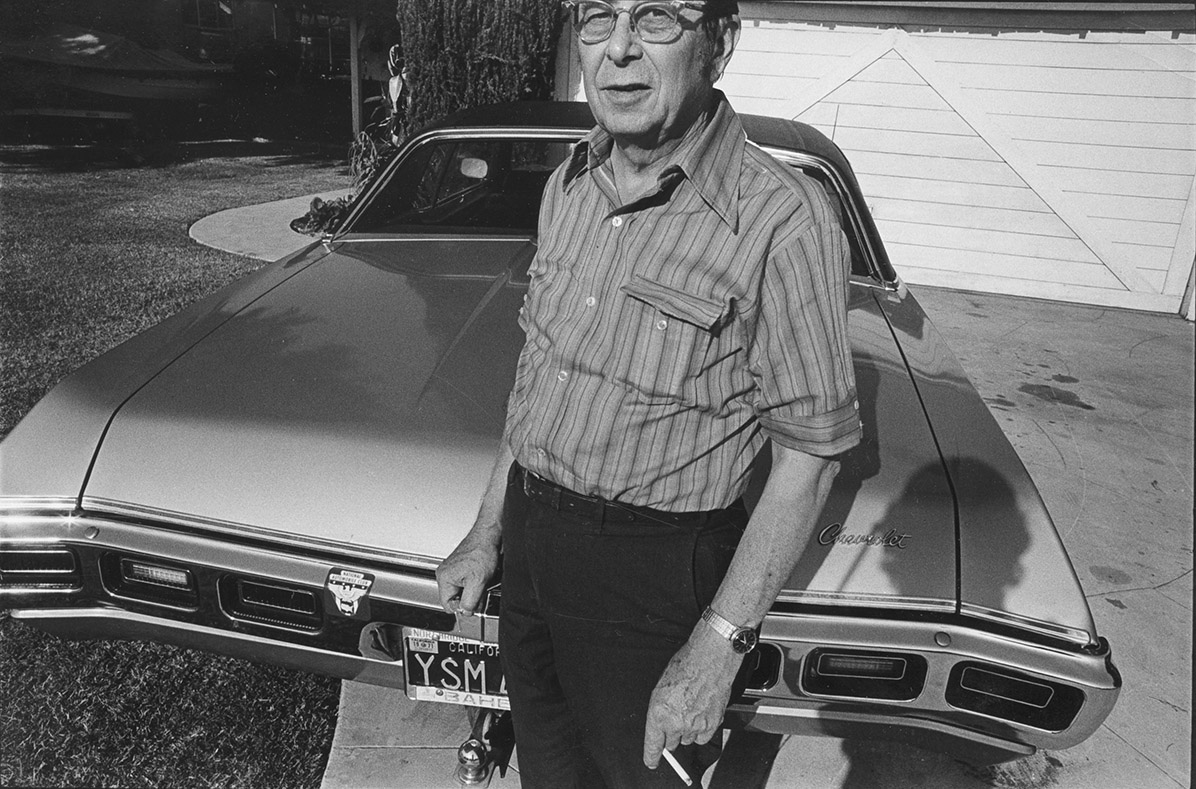

CSUN will run, from August 25-October 11, 2014 an art show devoted to the San Fernando Valley as it existed in the years 1970-1990. One of the artists, whose work will exhibit here, is Mike Mandel. I found some of his photographs on Flickr.

CSUN will run, from August 25-October 11, 2014 an art show devoted to the San Fernando Valley as it existed in the years 1970-1990. One of the artists, whose work will exhibit here, is Mike Mandel. I found some of his photographs on Flickr.

About, but not limited to, Van Nuys, CA.

CSUN will run, from August 25-October 11, 2014 an art show devoted to the San Fernando Valley as it existed in the years 1970-1990. One of the artists, whose work will exhibit here, is Mike Mandel. I found some of his photographs on Flickr.

CSUN will run, from August 25-October 11, 2014 an art show devoted to the San Fernando Valley as it existed in the years 1970-1990. One of the artists, whose work will exhibit here, is Mike Mandel. I found some of his photographs on Flickr.

Yesterday, near downtown Santa Monica, on a strangely cloudy and drizzly summer morning, I drove west, unintentionally, into blocked roads, past barriers and bulldozers.

Men were tearing down buildings, punching holes in plate glass windows and digging trenches.

The long winding humanitarian project known as the Expo Line had made its way from central Los Angeles, sweeping through Culver City, catapulting by bridge and track into West Los Angeles and finding itself and its destination next to the Pacific.

The empty shell of Midas, a beautiful Spanish Revival structure, lay in ruins, a stomach full of bricks and wood, its ornate ornament ready for obliteration.

50 years ago, the novelist Alison Lurie wrote a novel, “The Nowhere City” set in some places along the soon-to-be-demolished houses in the path of the Santa Monica Freeway.

Yesterday, near downtown Santa Monica, I saw the sequel to that book.

After half a century, the Nowhere City Goes Somewhere: on foot and bike and rail.

Richard McCloskey’s images of Van Nuys Boulevard in the early 1970s, the cruising and the cars, is now for sale at Art Prints.

The photos show young people having a good time while hanging out, congregating on the street, and in the shopping center, which still stands next to Gelson’s on Van Nuys Boulevard.

Cruising, as Kevin Roderick in LA Observed explains, “began before World War II, spread across LA with the car culture of the 1950s and 60s, crested when the baby boomer hordes were at their most numerous and bored, and finally faded after the LAPD shut down the boulevard in the 1980s.”

The GM plant in Panorama City (1947-1991) built many of the cars that roamed the street. It paid its workers well, who in turn bought cars and produced children to drive them.

The cars were fueled by cheap gas (29-33 cents a gallon) which ended after the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo doubled the price of fuel and forced Americans to abandon wasteful muscle cars.

Once the cars were gone, the pretty girls and the gritty guys packed up and went away.

Van Nuys settled into its current state of illegality, drift and decline.

From the USC Digital Archives come these photographs of flooding in Van Nuys at Tyrone and Sylvan Streets (a block east of the Valley Municipal Building) after heavy rains.

Caption reads: “Mrs. Agnes Snyder removes debris from car on flooded street. Wayne WIlson (bare foot) crosses St. Overall views of flooded Tyrone Ave. — cars submerged. Kids in stalled car.”

There are smiles on the faces of people, a lack of jadedness, that seems characteristic of that era. The hardship is harmless, nobody is getting hurt, the flooding is inconvenient and messy, but they are making the best of it.

Imagine the same situation in today’s Van Nuys.

A herd of fatties stuck inside their SUV, DVD player and boom boxes blaring, everyone on their mobile phones, three enormous women with tattoos, dressed in black leggings, broadcasting their “movie” on their smartphones with scowling and angry faces, never knowing how to live in the moment.

Things are moving along at 14741 Calvert Street in Van Nuys.

Things are moving along at 14741 Calvert Street in Van Nuys.

MacLeod (pronounced “mac-cloud”) Ale Brewing Company “a seven barrel production brewery with a tasting room” is in the midst of construction, with floors ripped open for pipes; and dirt, lumber, shovels and a lot of labor working hard to get this industrial space transformed into a functional operation by April.

Me and Andreas Samson stopped by yesterday, armed with cameras and curiosity, (and some guilt), as we stood next to men covered in dust and mud, shoveling dirt into trenches in preparation for next week’s concrete pour.

The owners are Scots born Alastair Boase and his wife, American Jennifer Boase, and the brewer is Andy Black. Beers will be British style.

The 10-mile long, $1 billion dollar widening of the San Diego Freeway is a monumental feat of engineering: demolition and reconstruction of bridges and roads, 27 on/off ramps, 13 underpasses and 18 miles of retaining and sound walls.

When the rebuilding stops, new car pool lanes will open.

Before that time, we, who travel or live in the Sepulveda Pass, go amidst temporary art installations. The partially built is perhaps more compelling than the finished product.

These functional components of road building are ingenious engineering and unaware artistry; choreographed, measured and precisely drawn elements of structure alive in rhythm, movement and shape.

Along the west side of Sepulveda at Wilshire (above and below), skeletal underpinnings, in wood and steel, for future on/off ramps, evoking the lean, linear infancy of modernism, form following function.

High pillars of steel hold up horizontal spans along Sepulveda, near the Veterans Cemetery and the Federal Building. Perhaps unintentional, the in-progress road suggests that this flat open expanse requires something triumphant and civic to pass through to salute government workers and honored soldiers.

Wood slats nearby evoke the organic asymmetry of Japan, while frail wood railings conjure up jungle bridges.

Near Montana, a tall hillside is clamped into place by ten-story tall concrete ziggurat criss-crossed by steel bars and round bolts onto which plates of facing will hang.

Here are dancing and unfurling materials, performing in shadow and sun, ribbons of road next to green mountains, tall walls of tapered concrete holding back tons of earth.

Serrated vertical lined concrete walls, go low and march along in rectangular pattern near the Getty. Parts of drain pipes sit alongside. A crane stands on the west side of the freeway near the Getty.

Near Mountaingate, the 405, seen from below along Sepulveda, sweeps up behind a tall wall, a freeway heard but not seen.

At Mulholland, the pass opens up to the Valley.

The mountains seem higher, the vistas taller and wider.

New steel spans are stacked under the old road, ready to perform their next feat of support to carry up a new bridge.

It is a penultimate, high altitude moment of reconstruction: intelligent, courageous and invigorating.

And up in Sherman Oaks, near Valley Vista, the sunny and self-satisfied homes of prosperity are caked in dust, caught in the bottom-end of the widening. The congestion is worse, the noise more constant, the torn-up streets taken over by bulldozers, trucks, fencing, excavation, speeding drivers, demolition and reconstruction.

A heroic human endeavor whose energies are producing, in our backyard, a fast changing and fascinating spectacle of clashing forms, tactile tons of man-made materials, anonymous art along the 405, silently begging us, as Los Angeles often does, to open our eyes and drop our assumptions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.