Weaker, yet still alive, still able to speak, Louise M. Hurvitz was in her wheelchair, in the sunshine near the glistening Marina boats, when she told me she wanted to eat a steak.

That was on Monday, August 18th. She ate a hamburger that night, and a slice of pizza on Tuesday night. She was 8 months into her Stage 4 lung and bone cancer.

Nurse Linda said she was looking great.

Then on Wednesday she began to call for her sister “Millie”. She was up all night, and then asleep all day by morphine and Lorazepam. In periods of wakefulness, her glazed eyes no longer looked at me, but out into nothing.

She was no longer able to speak. I went every other day to see her, knowing she was entering death.

A blue booklet left by hospice, Gone From My Sight, explained how the bedridden dying walked out of life. We noted her symptoms mirrored in the book.

The late afternoon sun was bright in her bedroom on Friday, August 22nd. She screamed that her head hurt, her back hurt, everything hurt. She wanted me to shut all the drapes. I abided and put the room in darkness. Foreshadowing.

She was in her last days. Nurse Bertha said if she ate she would stay alive. And then on Friday, August 29th, Labor Day weekend, hospice came and said, “no more food or water”. She was given 72 hours.

All weekend were the pleasures of Los Angeles, the beach and the beer, the walks along Abbot Kinney, the barbecues, I partook of some haunted by an upcoming phone call.

And then on Sunday, August 31st at 11:30 PM we were called and told she was breathing irregularly. We got in the car and rushed down to the apartment. My brother and sister-in-law were at her bedside. A nurse helplessly held the nasal end of the oxygen tube against her open mouth.

She was gray faced.

She was gasping for breath.

I replaced the nasal oxygen with a whole nose/mouth mask. Nurse Linda arrived. The hospice nurse came. It was about 2am and we did not know how long she would live. Exhausted we left. And an hour later I was in bed when my brother called.

“I hate to tell you this but Mom has passed.”

All the fighting for her life, all the medications, the food, the physical therapy, the chemotherapy, the consultations with UCLA medical doctors, the cat scans and the other radiology, the organic smoothies packed with nutrients; all the equipment, the oxygen, the ointments; everything done to keep her alive and going. Done.

Her body was pronounced dead by a doctor. The cremation company came to the apartment to wrap up and remove her.

We held a home service for her, almost a week later, on Saturday, September 5th.

Andreas Samson, my friend who writes Up in the Valley, attended and wrote a touching description of the bittersweet “party”.

There was food and drink, old photos on the flat screen television, a Spotify soundtrack of her beloved music (Frank Sinatra, the Fifth Dimension, Herb Alpert). Relatives who had never seen her sick, showed up to pay their respects.

And her life was presented selectively, with an emphasis on the young, beautiful, vivacious, pranking, intelligent, subversive sorority girl and network executive.

She, who died at 80, mothered a retarded boy, took care of an epileptic and ill husband, worried and fretted over children, finances, nightly meals, laundry and cleaning, her daily travails were wiped away or spoken of in one sentence salutes at our remembrance.

For 52 years, I had grown up and grown old with her. I knew her love and her craziness, her exasperating circular questions, her sparkling memory for names, faces, and events.

She, who drank vodka and grapefruit juice, and later switched to red wine, was probably an alcoholic. She was full of shame over events she had no power over, castigating and punishing herself.

But she fought hard to protect and to nurture, and daring to venture out of Lincolnwood, IL, moving to suburban NJ where she set up a new life with her family at 47, exploring Manhattan, New England and the East Coast with the curiosity and passion of a young woman starting out life.

She sold airplanes with a male friend, a pilot and airplane broker who lead a life outside of norms, a man who was later convicted of stealing money from his customers. He flew Louise and our family, often, to Albany, Boston, Martha’s Vineyard, Manahawkin Airport, Miami, East Hampton, Nantucket, Block Island, all around the Eastern Seaboard. American life was seen from 8,000 feet, little houses and little lives across the vast expanse.

She went into the city to see plays with my father, to walk neighborhoods, to buy groceries at Fairway, see exhibitions at the Metropolitan, attend concerts and events at Lincoln Center.

She read the NY Times and Bergen Record voraciously, keeping herself informed on culture and politics. The papers piled up in wet and musty mountains stacked in the garage.

She loved her new home in the woods, a place where the windows were always open and the rooms smelled of rain and leaves and florid humidity. In the spring, summer and early fall, the back deck, suspended on the second story of the house, was her outdoor space, a place of reading, eating, entertaining and midnight conversations by candlelight.

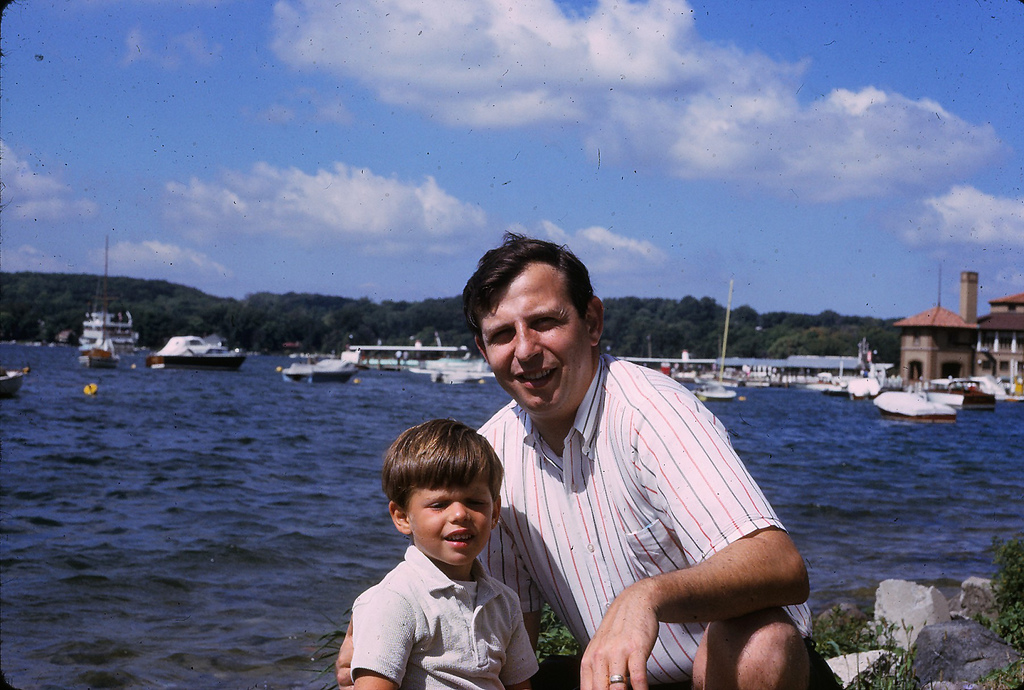

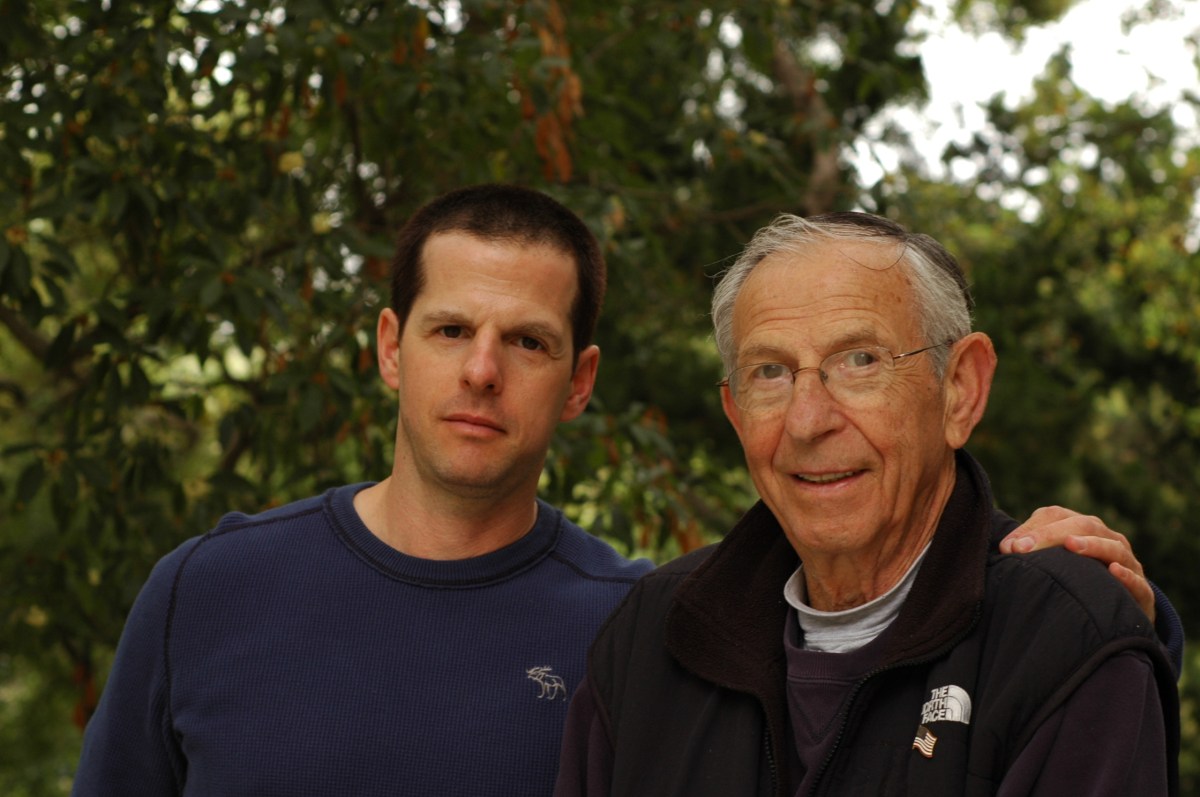

She lost my father after his long and agonizing brain disease, an illness that took 4 years to progress, rendering him an invalid.

But after he died, in her apartment in the Marina, she became a devoted grandmother and somehow earned the respect and awe of children who had once only seen sadness and burden in her exhausted eyes.

She was valiant onto the end; never giving into death, never acknowledging that life was less than the entirety. An iron dome of denial was her shield.

She was more than she ever admitted to being. She was magnificent in her life force, in her refusal to die, in her love for life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.