6/4/14

Yesterday I went, as I have for almost six months, to visit my Mom, ill with cancer, now in hospice, at her apartment in the Marina.

She can’t walk now, so she is either in bed, or lifted onto a chair, wheeled over and pushed out, into the sun, or more often, up to the TV, where many hours of daytime talk shows play without end.

She asked me to sit down, next to her.

She said there was an explosion of news about cancer cures and people whose terminal illness had been cured through “miraculous” immunotherapies. Would I look into this she asked?

Told that she was Stage 4, incurable, sick with bone and lung cancer, she has accepted the news, but fought it through inquiry and denial. She told me she was coughing more because she had caught a cold.

Loretta, her live-in caregiver, brought my mother into the living room, to vacuum the bedroom. The bedside phone rang, and Loretta handed me a call from Direct TV.

I answered in the voice of old gruff Junior Soprano. I told the woman we were retired people, uninterested in her offer, and hung up. My mother laughed, hoarsely, and said that she loved that voice I used.

She is still fully there, her mental capacity undimmed, even as life seeps out and the monstrosity of dying cells takes over.

I made a lunch of grilled salmon and roasted garlic, rice, fruit salad, plain yogurt, and hot green tea. If healthy eating were enough to insure health this meal might defeat cancer.

After lunch, Loretta wrapped my Mom up. And I pushed Mom in the wheelchair down to vote in the Marina City Club, where more old people manned tables and passed over registration books, which my mother let me sign.

I stood next to her and fed the flimsy two-holed ballot into its plastic holder, and began to read the names of politicians to my mother, who only knew one, Governor Jerry Brown. We read each page: names of candidates and parties running for offices; all enigmas.

Is an ignorant voter more dangerous than an intelligent one who abstains from voting?

We turned the ballot back in, having punched only one hole and we were given stickers that read: “I have voted”.

I took her to the park across Admiralty Way, a running and biking path between the speeding cars and the tall buildings.

Behind the Ralph’s parking lot on Lincoln, there was a small opening in a fence, and I walked down to see if we could get through it. I judged that we could, and I pushed my mother in her chair over the asphalt onto the bark’s decline, through the fence hole and past the dumpster into the parking lot.

She hadn’t been inside a store in six months, and now, where she had once driven herself and walked in, she sat as she was pushed past edibles.

We picked up extra virgin olive oil, aluminum foil and wheeled back to the Marina City Club.

I seem not to cry much when I visit, acclimated am I to the new grimness.

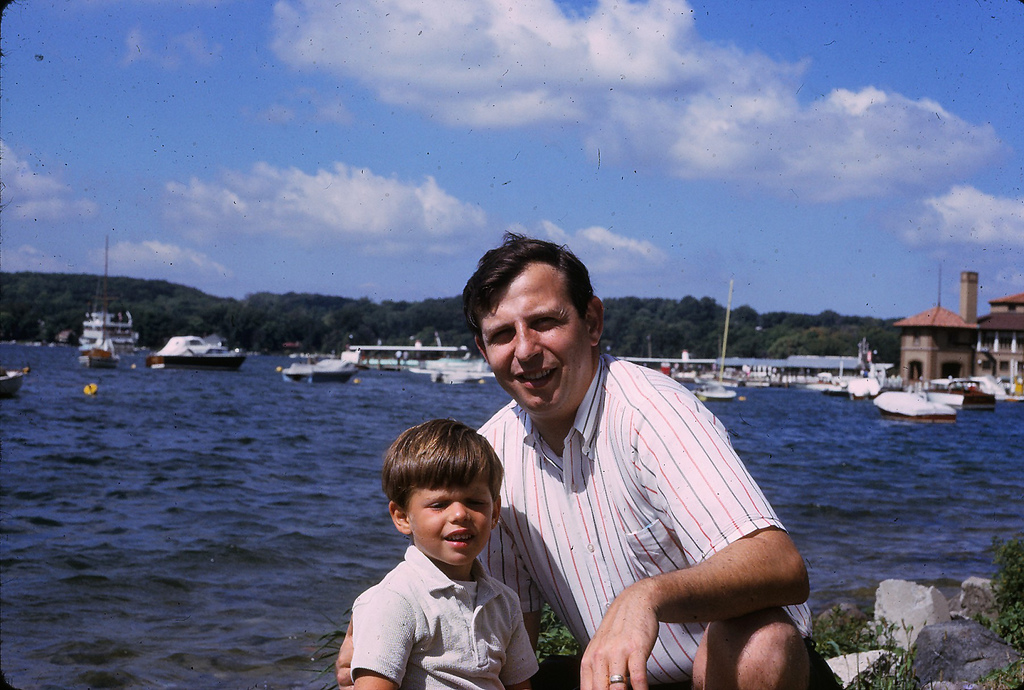

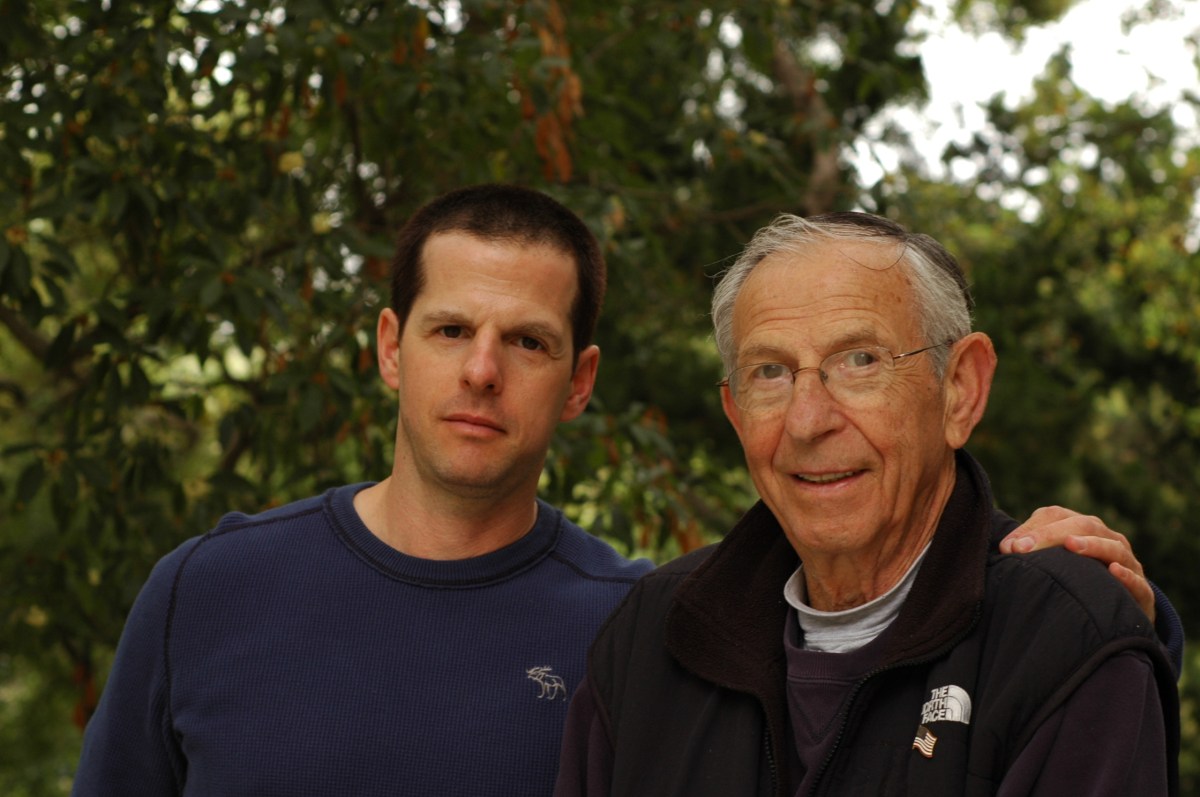

I became, in the last six months, a high-ranking soldier: inspecting the medicines, giving orders to the homecare workers, pulling in supplies, taking over financial, legal and medical decisions, signing papers, managing staff and bringing drugs to the ill and dying, issuing directives for non-resuscitation and cremation.

I had no training, only a sense of duty, obligation and rightness.

When I left yesterday, in the late afternoon, I kissed my mother on the cheek and held her hand, and wandered out into the wind propelled in blank distraction.

From this time afterward I existed in a suspended and stoned state of mind, up on Abbot Kinney drinking wine, and later, intoxicated, walking up alleys and behind buildings camera in hand, anesthetized and numbed.

A woman sitting on the sidewalk, not homeless just sad, stopped me and asked me about my camera. Tina introduced herself. She told me her husband was divorcing her and taking custody of their two children. She asked if, one day, I might want to take photos of her and the children. She told me I should volunteer at Venice Arts and teach kids photography.

I was on wine so I was kind. I listened and gave her my card.

I think I will be like this for a while, even after my mother dies.

Peace will settle on me like a healed burn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.