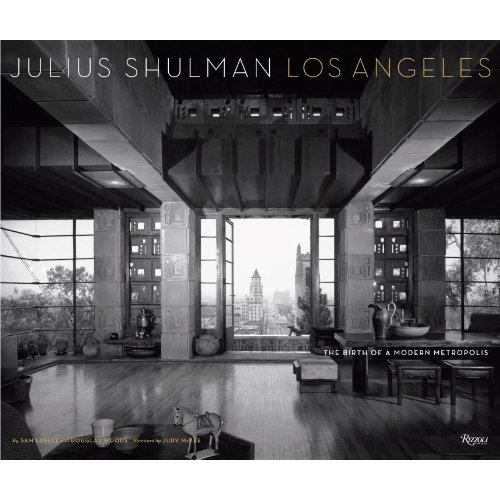

The world needs another book on the late photographer Julius Shulman (1910-2009) like it needs another Katherine Heigl movie, but there I was, last night, driving to Woodbury University, to attend a book signing for the new Rizzoli photography book, “Julius Shulman and the Birth of a Modern Metropolis” by Sam Lubell, Douglas Woods, Judy McKee (Shulman’s daughter) and illustrated, of course, with Mr. Shulman’s voluminous and gorgeous architectural images.

In an auditorium, a large screen was set up in front of the audience. At a long table sat Craig Krull, whose gallery sells Shulman’s infinitely reproducible photographs for thousands a piece; a woman from the Getty Research Institute/ Julius Shulman Archive; Judy McKee, Julius Shulman’s only child and the executor of his estate; authors Sam Lubell and Douglas Woods; and architecture critic and author Alan Hess.

Shulman’s photography was the clearest and finest representation of the California dream after WWII. Through his lens, the world saw a state of endless innovation and mass-market modernism where mobility and technology might remake the lives of millions under the glowing sunshine.

Architects Neutra, Eames, Koenig, Lautner and Beckett hired Shulman to promulgate, promote and propagandize modern building and modern design. Through the 1950s and 60s, every freeway, every parking lot, every shopping center replacing every bulldozed orange grove was an opening to a grand and glorious future. The lone skyscraper in a sea of parked cars was held up as a model of how life should look. And Shulman was the master who made the desert of Los Angeles bloom.

The skyscraping of Bunker Hill, the lifeless streets of Century City, triple-decker freeways– they all were shot at the end of the day: shadows, textures and gleaming surface.

Mr. Krull called Mr. Shulman “the most optimistic man I’ve ever met.” Like Ronald Reagan or Arnold Schwarzenegger, Shulman loved the Golden State and kept his company with the most successful and accomplished men of his time.

The speakers last night, acolytes and worshippers, reinforced each other. The academic praised the archivist who saluted the authors who thanked the gallery who paid homage to the photographer.

Like Scientology, that other great religion of this region, Shulmanism demands fealty and loyalty to its founder and his work. To ask why Los Angeles has never lived up to its photographic glory is to risk blasphemy. To ask why Shulman, who lived for almost a century, did not turn his very observant eye, onto the less attractive parts of LA, is to insult the very vision and mythology he produced.

Mr. Krull also said that Mr. Shulman never thought his photographs were worth so much until the checks came in. Photography is reproducible… but oil painting, sculpture and the Hope Diamond are not. No doubt, Mr. Shulman knew that each of his negatives could turn out 3 million photographic prints. But art collectors and art sellers must be smarter than the rest of us. And Shulman’s work is the gift that keeps on giving. Publishers, filmmakers, galleries are going to go on licensing Shulman for as long as they do Warhol, Presley and Monroe.

Projected onto Shulman is the very ideal that modernism was moral. Once upon a time, myth-makers imagine, architecture was about making the world a better place. By omitting broken down and shabby Los Angeles, and posing happy children, well-dressed wives and various home furnishing accents, Shulman decorated and embellished his structural subjects. With biblical fervor and pixelated proof, these photos demonstrate to believers that paradise did indeed exist in post-war Los Angeles County.

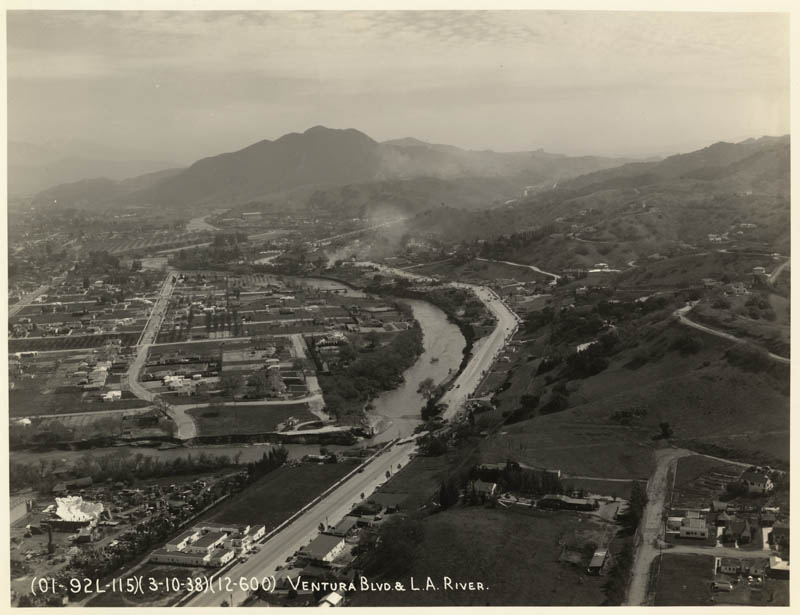

At the end of the presentation, one of the authors spoke about his favorite photograph in the book: a 1930s image of a thriving and ornate corner of downtown Los Angeles with streetcars and pedestrians.

You must be logged in to post a comment.