Yesterday, after many years, Tony, an old friend I had in New York in the early 1990s, who later relocated to LA, and then fell out with me, reconnected.

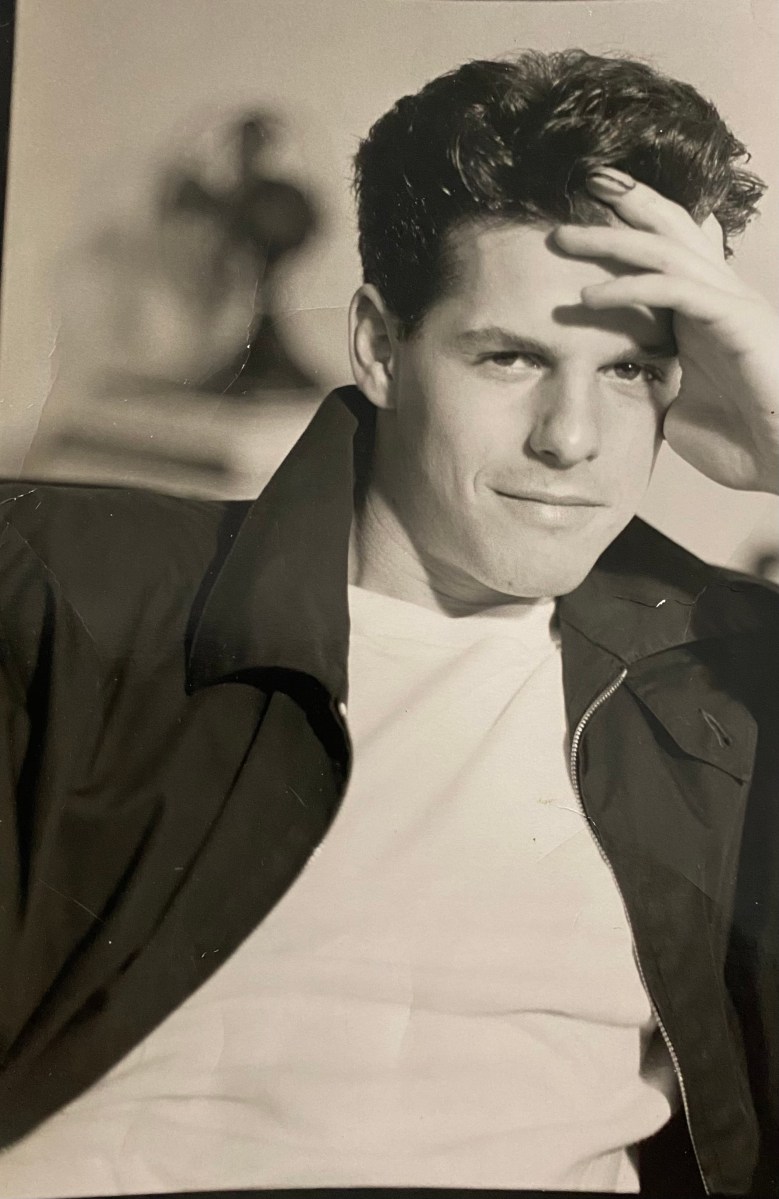

He is a funny, acerbic, self-deprecating person, a kind of Persian nomad who had grown up in several countries and had an upbringing that seemed to be made up of stories about how he was descended from noble, aristocratic people until everything went downhill sometime between the WWI and the fall of the Shah in 1979.

We had a friend in common, Eddie, who grew up as an affluent kid in Westchester Country, later studied with Tony in upstate New York, then got his graduate degree in landscape architecture and spent 30 years working for the City of New York.

We were young and gay in Manhattan in the late 80s and early 90s, and only 1 out of 3 of us were out and that was Tony.

Like me Tony was eccentric, undirected, mercurial, creative, given to sudden swings in moods, yet very loving and then very angry when he detected dishonesty, exploitation or unfairness.

In 1988, I was 26 and I met Eddie Moscow on the beach at Amagansett. I was one of ten in a share house, and he was staying nearby at his parents’ beach house which his schoolteacher father bought in 1966 for $30,000.

Eddie and I immediately bonded. We were both the same age. We shared an interest in architecture, pop culture, and New York history.

His first question to me after he met me: “What have you been doing for the past four years?” He couldn’t understand what I had planned after I graduated from Boston University in 1984.

40 years later I still don’t have an answer.

That summer I lived with a group of ambitious, self-centered young Manhattanites; actors, models, the owner of a public relations firm. Everyone was jockeying to get ahead. We rode around in one guy’s jeep visiting the mansions of people who we deemed important.

Eddie was the real anchor of that summer because he didn’t live in that house. He befriended me when I opened up how I hated the people I was with. He invited me to “crash” at his apartment on East 38th St.

We got to be close friends, but it was platonic because Eddie wasn’t gay. He liked design, mid-century furniture, riding around in his little convertible Miata. But he wasn’t gay.

I moved into New York in October 1988 into a rented room on MacDougal Street. One time Eddie came to visit me and sat on a stoop outside my apartment until I came down.

He told me that while he was sitting there a nice, young guy came by and started to talk to him, told him he looked familiar, and was very, very friendly. He later realized it was Matthew Broderick.

I worked nearby selling advertising for the New York Press. Then abruptly, I quit my job. Without reasoning, I just was unemployed. And then I got a job in a home furnishings retail store on West Broadway called Turpin/Sanders. I truly hated this position, because it involved polishing glasses and selling tableware.

After some three weeks, a young Puerto Rican man came in and started cruising me. We met at lunch and we ate pizza at a park near Thompson and Spring. He told me he worked at Polo Ralph Lauren and I should apply there because “you have a look.”

He said he would recommend me to the store manager, 25-year-old Charles F., and that I should say when interviewed that “Polo is a lifestyle.”

I went for the job interview, conducted in the mahogany paneled top floor of the Rhinelander Mansion at 867 Madison. Charles F. asked me what Polo was about.

“Lifestyle,” I answered.

I was hired.

I was placed in the boys department, and Charles F. selected my clothes which were 65% discounted but came out of my own expenses. I had a blue blazer with a crest, yellow oxford shirt, rep tie, hard leather shoes, grey flannel trousers. Later we made a bus trip to a Polo outlet in Maine and I got a tweed suit, a pinstriped suit, waistcoats, belts, argyle socks, another tweed jacket, more neckties, more shirts.

I stayed there for four years, folding clothes, waiting on rich customers, and funding a 401K with 3% of my $30,000-$40,000 a year earnings.

In 1988, I had taken a screenwriting class and met New Hampshire émigré Beth. We became friends, platonic friends, and I would sleep over at her 5th Floor walkup apartment on 2nd Avenue near 17th Street which she shared with two other men.

Her living room was subdivided into four rooms, and into one of these a young executive from Tustin, CA moved in. His name was Jerry and we also became friends.

Jerry was engaged to a woman from Scotland and they were planning to get married in 1990.

We often went to the Royalton Hotel and sat in the all-white lobby with the all-white armchairs and drank white wine or Anchor Steam. Eddie would meet us there. Me, Jerry and Eddie.

One day Jerry and I were sitting in the hallway stairs outside of the 5thFloor walkup. A windowed light well with many pigeons illuminated us.

“I like you Andy,” he said rubbing my shoulders.

We began a clandestine relationship. His fiancée couldn’t know. His landlord Beth, friends with his fiancée, couldn’t know. And that night when I lay next to Beth, I just got up and walked down the hall to Jerry’s room.

Just like that.

“Eddie Moscow is really handsome,” Jerry told me.

They became friends. Eddie had a habit of meeting people I was friends with and then befriending them. I didn’t really care.

But then I told Jerry I didn’t really want to date him.

And he was hurt. He teamed up with Eddie, whom he liked, and then Eddie and Jerry dropped me as a friend, Eddie wrote me a hostile letter about how I had hurt Jerry.

That was the summer of 1989.

It was the last of Eddie.

Sometime in 1991 I had dinner with “Tony the Persian” and my friend Jim at a Cuban restaurant on Amsterdam. Tony told us that he and Eddie were living together on Roosevelt Island and that Eddie was, yes, indeed, gay.

On Yom Kippur, Eddie, perhaps feeling he needed to atone for his sins, wrote me a kind letter. He may or may not have apologized but he wanted to become friends again.

I forgave him and we went back to meeting up for dinner, cooking pasta, drinking red wine, at his new apartment near Central Park West. He had cashed out some stocks for $10,000 and spent it on upgrading the electrical, painting, buying furniture and new appliances.

We worked out at the New York Sports Club where they charged $70 a month for Nautilus machines and some free weights.

We were now 30 and it was 1992, and then Eddie met an older man at a party named Devin. Devin and Eddie spent every minute together, and I was out again, the third wheel.

Dramatizing, castigating, haunting all in the background was Tony. He had always loved Eddie. Now Devin was in the picture. Tony and Eddie always battled, throwing insults back and forth.

Eddie’s parents were from the Bronx and they had that unalterable aroma of Bronx about them, especially the mother, Mrs. Moscow, who despite wealth, still spoke as if she were fighting other women for bargains in the bins at Loehmann’s.

Eddie would make fun of Tony as a Persian, for liking dolls, and Tony would attack Eddie’s family. The vocabulary Tony used to describe Eddie’s sister, brother or mother: obnoxious, vulgar, loud, crude, awful, sickening, disgusting, horrendous, selfish.

Eddie had an older brother who was a lawyer. He was gay. He begged Eddie not to come out of the closet “as it will kill our parents!”

The suffering of parents to know the truth about their children was an enforcer of morality. Everyone lied until they couldn’t.

The Moscows acquired a rare piece of land at the eastern end of Amagansett next to a wilderness preserve.

They budgeted $600,000 for a seven bedroom, four bath house on the dunes. And Eddie Moscow was in charge.

The house was a severely symmetrical Shaker style with beige siding and rows of little pointy topped pavilions attached together, culminating in a 35-foot-tall living room “the tallest in Long Island.”

The interior was polished light wood floors and the laundry room was based on a design Eddie had grown up with on “The Beverly Hillbillies” where the plumbing and electric outlets were hidden behind the washer and dryer.

In back was a large wooden deck with an inground swimming pool. And a few hundred feet further was the Atlantic Ocean.

When the house was done, you would sit way down in the living room and the ceilings were so high you would feel like an ant in a cathedral.

The family still owns the house. The parents are dead. It is listed online and rents for nearly $200,000 a month.

In 1992 I went to the dentist and they found that I had severe gum recession. A periodontist recommended gum surgery where they would remove skin from the roof and side of my mouth and sew it into my lower gums to prevent loss of teeth.

I got the surgery and spent a month on protein drinks, yogurt, bananas and soft foods.

I was living on West 96th Street in a rent-controlled walk up for $560 a month. I still worked for Polo and commuted to work walking through Central Park. A few times I saw John Kennedy, Jr. playing touch football.

I also had several panic attacks in the fall of 1993. I was terrified of riding on the train, of taking medicine, or riding in elevators. It was a condition I treated with cognitive reasoning and psychotherapy. Under all of it I was terrified of AIDS.

I got the flu. I asked my mother if I could come home to New Jersey. She drove across the Tappan Zee Bridge to wait for me at the train in Tarrytown.

On the train I had a panic attack. I remember collapsing and shaking and a kind black woman comforting me and my admission to her that I was gay, and then the conductor calling an ambulance and when the train arrived my mother was waiting and angry and they took me on stretcher to the hospital and gave me a valium to calm me down and my mother looked at me with venom.

“Your father can’t know any of this! It will kill him! I knew when that ambulance came to the station it was for you! I just knew it!”

The suffering of parents to know the truth about their children was an enforcer of morality. Everyone lied until they couldn’t.

Not once do I remember Eddie Moscow caring about my mental breakdown, offering an emotional assistance, or helping me. But he was still “my best friend.”

The last fall I spent in New York I met a rich medical student whose parents lived nearby at 560 Park Avenue.

Dave went to Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx and had a loft apartment on Astor Place.

This time I was in love. It seemed that this would be the guy.

I would stay over at his apartment. I met his school friends, and a cocky filmmaker Mark who made short features about gay people.

What were we going to do for New Years? Dave had his plans.

He broke up with me.

I got fired from Polo in February 1994. I had poor sales figures, I was there nearly five years, and I was not going to work in their executive offices.

“Why don’t you come to LA? We can write a script for Roseanne?” a friend who rented a house in Studio City asked.

I made plans to move. I told Eddie Moscow.

“Please don’t move to LA!” he said.

His new house was nearing completion. The family moved in. All they needed was landscaping around the house.

On my last weekend in New York, before I moved to California for good, best friend Eddie got several of us to come and stay at his new house and work unloading large trees and large buckets of sea grass, and take hundreds of plants off the truck and, under Eddie’s direction, dig in the sun on the sand to landscape the mansion so Eddie’s parents could save money on professional landscaping.

Just a few days ago Tony, nearing 60, also no longer friends with Eddie Moscow, contacted me. He lives in LA. He has had a variety of jobs, most notably involved with Barbie and Mattel.

He recounted the tragedies that have hit him in only the last five years: his sister jumped out of a window and killed herself, his twin brother addicted to drugs died of an overdose, and his dementia suffering mother passed away.

This early dying is apparently a very American story, as David Wallace-Wells writes today in the New York Times. America far outpaces any other western society in the early deaths of its people from drug overdoses, gun violence, car crashes, obesity related illnesses, suicide, and Covid-19.

By coincidence, yesterday I was glancing at a book published in 1923, “The Bungalow Book.” by Charles E. White, Jr. It contained house plans and essays about styles, construction, and fireproofing.

In the chapter of preventing fires, White writes about the American disregard for human life.

Americans as a class hold human lives more cheaply, perhaps, than the citizens of any other land. We are all inoculated with an inborn indifference to hazard of life, not only of the lives of others but our own lives, for to give the American his due he is courageous to the point of foolhardiness when his own life is concerned.

On Sunday, August 6, 2023 at 11pm, a wrong way driver on Victory near Columbus, (two blocks from my house), drove into another vehicle and killed a 64-year-old male driver, attorney Vatkes Nalbandian.

Somewhere in all these memories, in all these recounting of petty things, and horrific events that struck others, and small hurts and large failings, is a theme of indifference.

What are we doing to each other without thinking, caring, empathizing?

My father called it nihilism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.