A housing and planning blog I read, Granola Shotgun, recently had a post about how the author is hassled for taking photos in public for such elements as parking lots, buildings, encampments or anything structural connected to a human.

In the past 15 years, since I started this blog, I have had similar experiences of being confronted when diligently just recording any exterior anywhere because it captured my imagination.

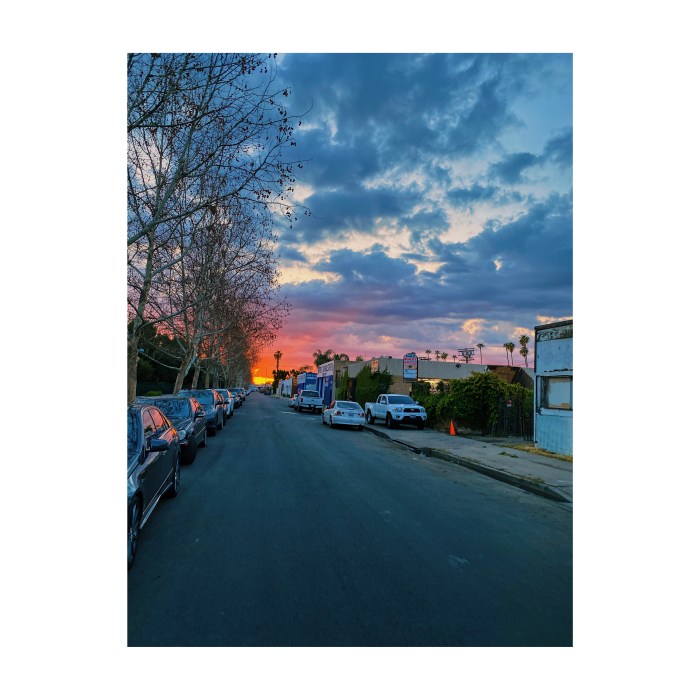

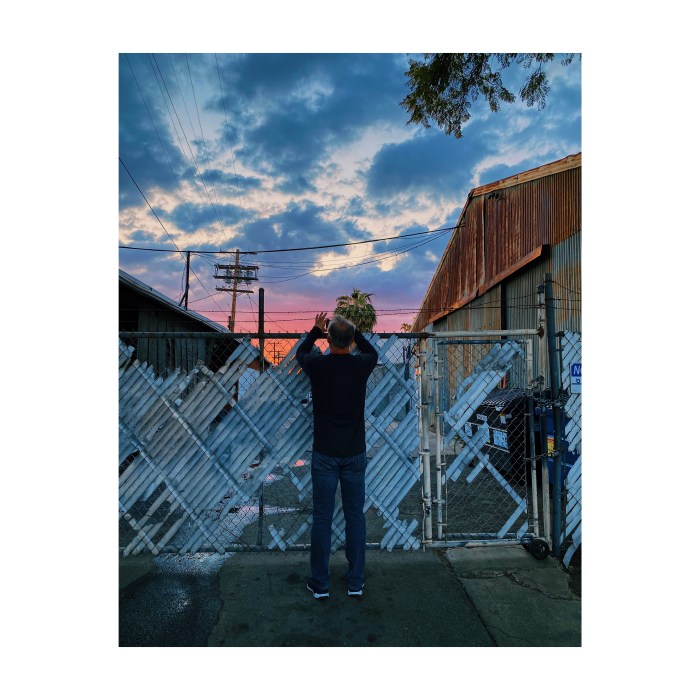

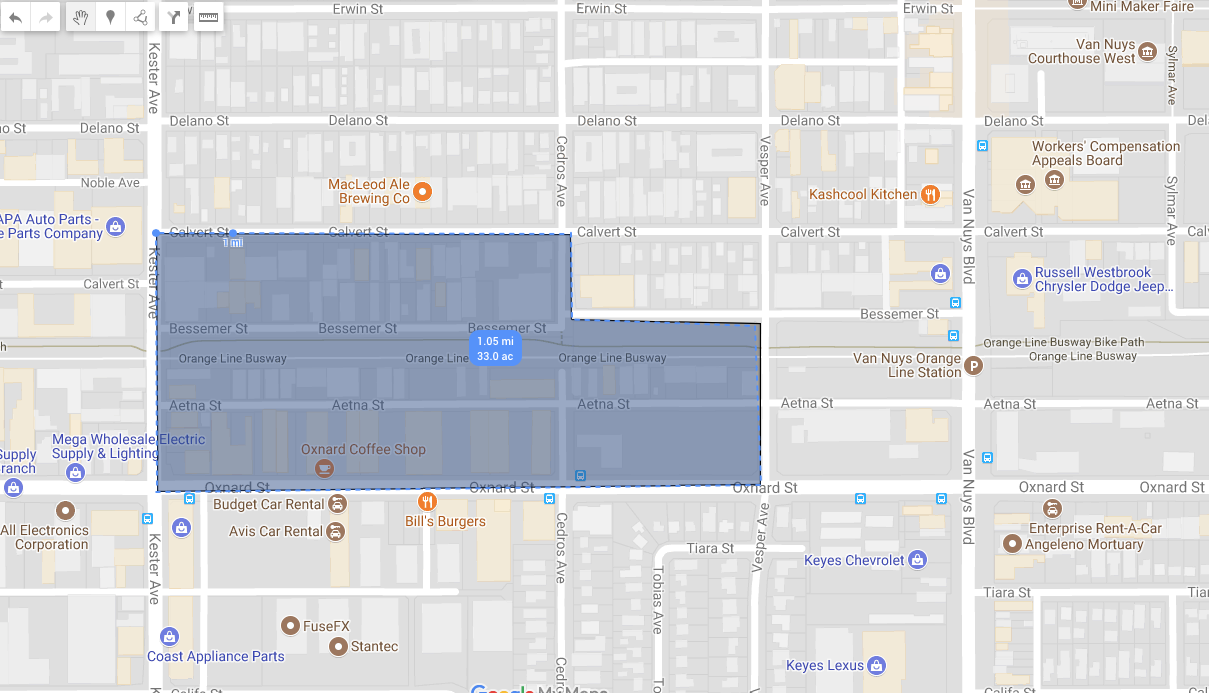

As recently as March 2020, on the last night I went out to drink at MacLeod Ale, I left the brewery. I was with a friend, who also had a camera. The sun was setting. The light was golden and glorious. I had my Fuji XE3. While walking on Calvert towards Cedros, I started photographing many things that the light was hitting, including the exterior of an auto body shop.

Several tough, menacing looking men were conversing across from the shop. One yelled at me, “Hey! Why you taking picture?” he said.

I had a few beers so I answered, “Because I want to. I’m not on private property and the sun looks beautiful on that building.”

“What building? What sun? What you talking about?” he answered.

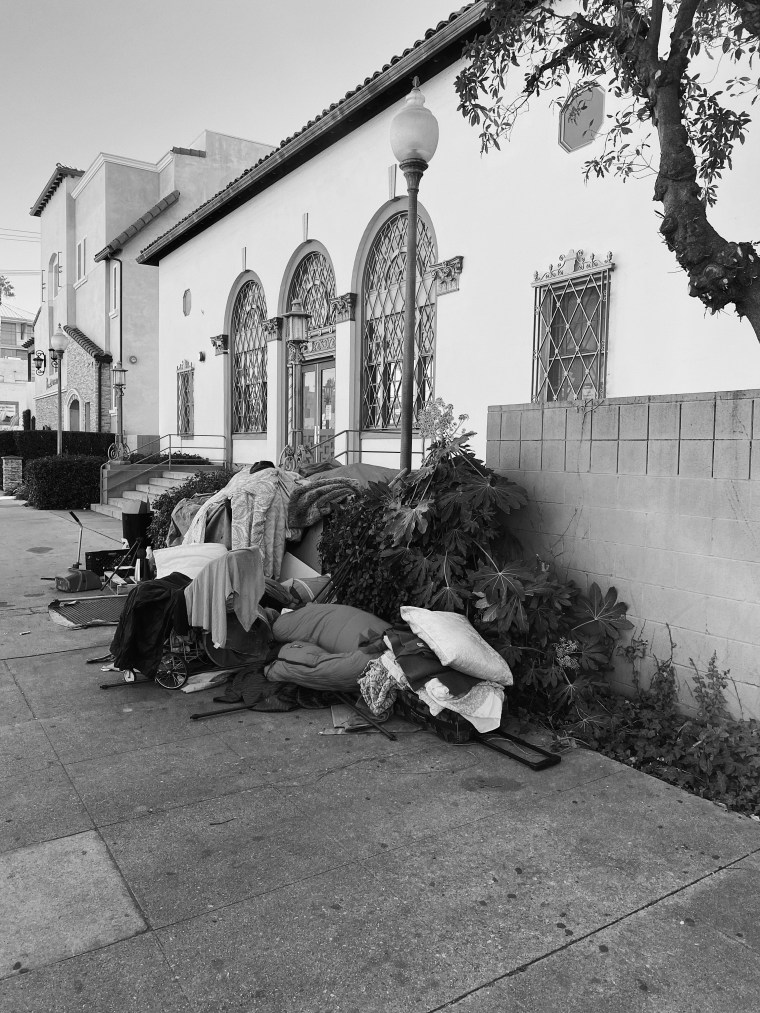

We walked over to Bessemer St. through the trash of a block long homeless encampment, (which I wouldn’t dare shoot) which once would have been illegal and immoral, but is now normal. People living, shitting, drinking, sleeping on the street. By the tens of thousands. OK in Garbageciti.

On Bessemer, as we got into the car, a tinted window Mercedes SUV drove by slowly, eyeing us, letting us know we were under his surveillance. Nothing happened, but we drove away chilled at the implicit threat.

I write and photograph about the urban condition of my neighborhood. I do it with the intent of telling the truth, not to promote my product or sell a political dogma. A billboard on Kester at the golden hour is just a billboard.

In 2006, I was photographing the exterior of the historic Valley Municipal Building on a Monday morning. An older woman came out, not a security guard, just an older woman, and she screamed, “What are you doing! Why are you shooting this building!” She had a car, and she drove up to me as I walked along Sylvan St. asking again what I was doing.

“There are people who want to harm this country!” she said through her window.

Like her. Opponents of constitutionally protected free speech.

Photography is politicized now, like everything else. A public photo in Los Angeles is assumed to be:

- ICE finding undocumented people.

- TMZ trailing a celebrity.

- Location scouting for a porn.

- A developer intent on building something.

- A Karen uncovering a violation.

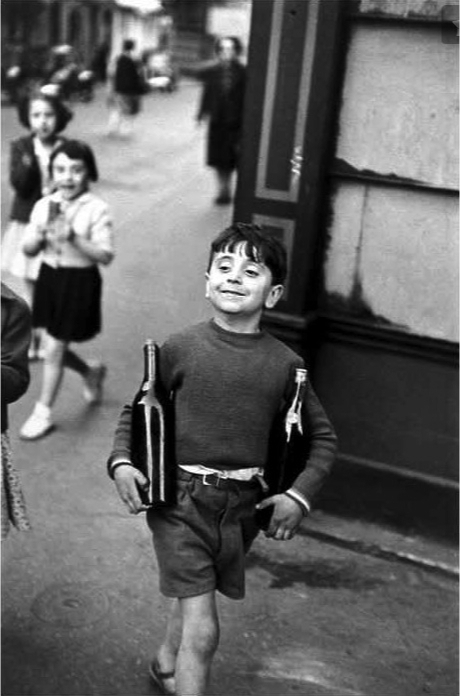

Will a photograph ever just be a photograph again? Could Robert Doisneau or Henri-Cartier Bresson shoot children on the street today? Or would they be confronted by parents or teachers or strangers asking what the hell they were doing?

How did it come to be that a joyful, celebratory, observant act, public photography, become so reviled and feared? We live in a time when every person has a camera on their phone, so anyone can really take a photo anywhere at any time, yet the deliberate, artistic, considered flaneur, strolling through the city after a few glasses of wine, can be confronted if he carries a traditional camera and aims it at strangers.

Then there is the aspect of shame. We have no public shame anymore. People dress, eat and behave in ways that would largely be considered shameful by 1945 or 1970 standards. So shame is employed as a tool by the weak, sometimes used against others who are weak, but often to gather like minded bullies together to defeat free-thinkers.

These examples of 21st C. public dress and obscene signs would have probably been against law or custom 60 years ago. Just as today it would be unthinkable for grown man with a camera going up to a children crossing the street and photographing them, as Henri Cartier Bresson did in Paris 80 years ago.

The public no longer knows what is properly public and what is not.

When private people prohibit public photography, they often think they are exercising the rule of law. Security guards fall into this category. Yet they stand on weak ground. No building, other than a military installation, has the right to not be photographed.

And we live in time of political intention. Every act is political. One can identify with a political party by wearing or not wearing a virus guarding mask, or drinking soda with a plastic straw, living in a gated McMansion, expressing sympathy for the police, or wearing a red baseball cap. All can get you harmed or doxxed.

At the 2017 Woman’s Rights March, I went out with several older neighbors and of course I had my camera. It was a historic moment. And I photographed a crowd near Universal City. Which provoked a young guy, masked in bandana, to walk up and demand to know why I was photographing.

There is nothing illegal about photographing people in public. Or buildings. Even outside a schoolyard, even families picnicking in the park, even photographing a parking lot in a poor area of Van Nuys. These are all legal and protected by law.

But no law protects against widespread public fear of freedom of speech. When enough mobs band together to ban something you can be sure it will be. Photography by photographer is on the list of once free rights that face censoring, cancelling and expulsion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.