The proposed Metro Los Angeles scheme (“Option A”) desires, through eminent domain, to flatten 186 small businesses employing some 1,500 workers just steps from downtown Van Nuys.

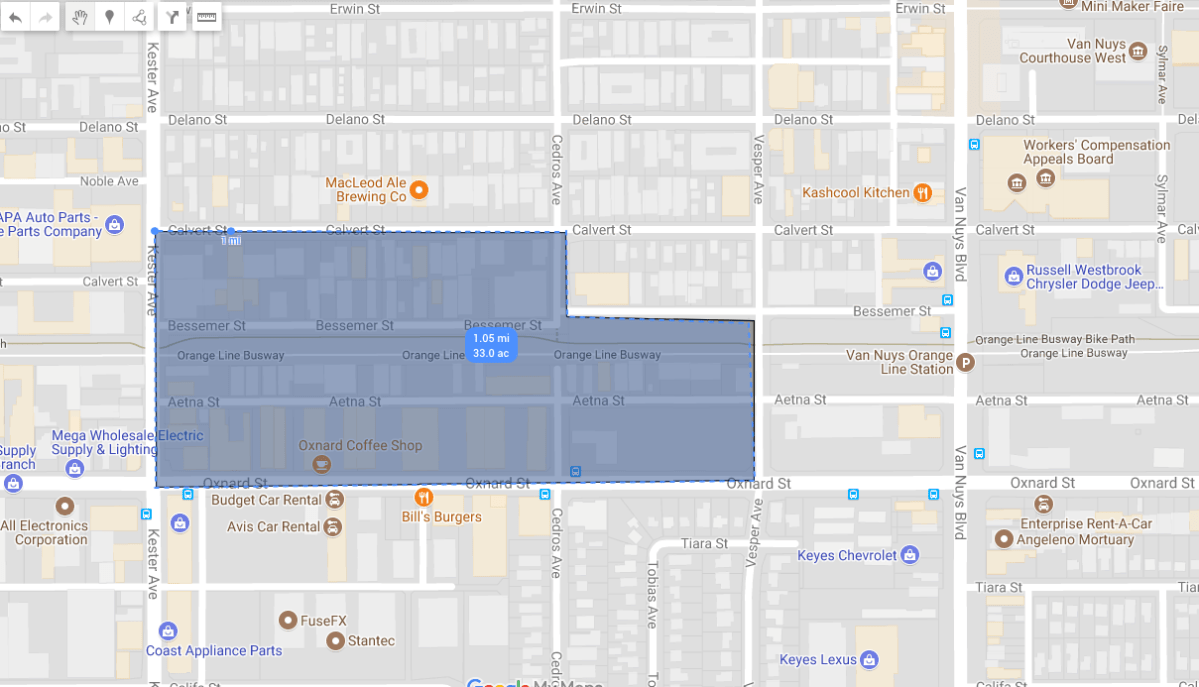

The 33-acre area extends from Oxnard St on the south to Calvert St on the north, Kester St. on the west and Cedros on the east. In this area, rows of shops straddling the Orange Line will be extinguished by 2020.

Light rail is coming, the trains need a place to freshen up, and here is their proposed outdoor spa.

The engine of public relations is roaring. Mayor Garcetti needs to remake LA for the 2028 Olympics. He has gotten the city into full throttle prepping for it.

It is comforting to think that property owners will be reimbursed for their buildings, that businesses “can relocate”, that the city will take care of those who pay taxes, make local products, and employ hundreds.

But most of these lawful, industrious, innovative companies only rent space. Yes, they are only renters, and they face the dim, depressing, scary prospect of becoming economic refugees, chased out by their own local government. Some of these men and women have fled Iran, Armenia, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico, places where war, violence, corruption, drugs and religious persecution destroyed lives and families.

Others were born in Van Nuys, those blue-eyed, blonde kids who went to Notre Dame High School and grew up proud Angelenos, driving around the San Fernando Valley, eating burgers, going to the beach, dreaming of making a good living doing something independently with their hands.

They all expressed shame, disappointment, anger, and betrayal against Councilwoman Nury Martinez and the Metro Los Angeles board for an action of insurmountable cruelty: pulling the rug out from profitable enterprises and turning bright prospects into dark.

Scott Walton, 55, whose family purchased the business Uncle Studios in 1979, said, “I think I’d sell my house and leave L.A. if this happens. I would give up on this city in a blind second.” His mother is ill and his sister has cancer. His studio now faces a possible death sentence.

What follows below are profiles of three men, who come from very different industries, but are all under the same threat.

Bullied at the Boatyard: Steve Muradyan

At BPM Custom Marine on Calvert St., Steve Muradyan, 46, services and stores high performance boats at a rented facility. Here are dozens of racing craft costing from $500,000-$1 million, owned by wealthy people in Marina Del Rey and Malibu. The boats winter in Van Nuys, where they are expertly detailed, inside and out.

Mr. Muradyan, a short, broad-shouldered, sunburned man with burning rage, threw up his hands at the illogic of his situation. He takes care of his wife, two children, and aging parents. He pays 98 cents a square foot in 5,000 SF and he cannot fathom where he might go next. A wide driveway accommodates the 50 and 70-foot long boats. And he can work late into the night drilling and towing, without disturbing others.

He once ran an auto repair shop on Oxnard. Later he had a towing service. Then he started his boat business in 2003. He had raced boats as a young man, and this was part of his experience and his passion. Why not?

He deals with all the daily stress of insurance, taxes, payroll, equipment breakdowns, deadlines, customer demands, finding parts, servicing the big craft. He worries about his business, his family, his income. And now this impending doom, dropped from the skies by Metro. He prays it will not happen to him. He cannot fathom losing it all, again.

Art and Soul in Stained Glass: Simon Simonian

Over at Progressive Art Stained Glass Studio, 70-year-old architect and craftsman Simon Simonian rents a small unit on Aetna where he designs and molds exquisite stained glass for expensive homes, churches, synagogues and historic buildings.

He knows all the local businesses, and often he sends customers to the cabinetmakers and metal honers steps away. There is true collaboration between the artisans here.

A kind, creative man with a penetrating gaze, Mr. Simonian, with his wife and young son, came from Tehran in 1978 to study in Southern California and escape the impending revolution in Iran. He speaks Farsi, English and Armenian.

He is an Armenian Christian and his family was prosperous and made wine. His father had escaped the turmoil in Armenia when the Communists took over after WWII, which was also preceded by the massacre by Turkey of 1.5 million. His people have suffered killing, expulsion, persecution, and the loss of dignity in every decade of the 20th Century.

The Simonian Winery was doing well in Iran in 1979. And then the Islamists came to power and burned it down. By that time Simon and his wife and son were in Southern California. He begged his father to come but the old man stayed in Tehran and died five years later.

Tenacity, survival, and intelligence are in his genes.

“I love what I do. I have loyal customers. The location is excellent. I know all my neighbors here. I want to stay rooted. I don’t want to have to start all over again. Where can I find space like this? Where will I go?” he asks with the weary experience of a man who has had to find another way to proceed.

The Man from Uncle: Scott Walton

55-year-old Scott Walton looks every bit the rocker who runs the recording studio. He is longhaired and lanky. With a touch of agitation and glee, he slips in and out of the dark, windowless rehearsal spaces of Uncle Studios, where he has worked since 1979.

His father, with foresight, loaned $50,000 to his two sons, Mark, 20, and Scott, 17 to buy a recording studio. Here the boys hosted thousands of aspiring musicians including Devo, The Eurythmics, Weird Al Yankovic, Weather Report, Yes, Black Light Syndrome, No Effects, The Dickies, Stray Cats, and Nancy Sinatra.

When Scott first started he didn’t play any music. He learned keyboard, classical piano and he also sings. He went on the road, for a time, in the 1980s, playing keyboard for Weird Al Yankovic. He also plays in Billy Sherwood’s (“Yes”) current band.

Despite the proximity to fame, talent, money and legend, Uncle Studios is still a rental space where young and old, rich and poor, pay by the hour to record and play music. Something in the old wood and stucco buildings possesses a warm, acoustic richness. Music sounds soulful, real and alive here, unencumbered by the digital plasticity of modern recordings.

But Scott Walton is also a renter. He does not own the building bearing his business name. If his structure is obliterated, he will lose the very foundation of his life, his income, and his daily purpose. He will become an American Refugee in the city of his birth.

This is only a sampling of the suffering that will commence if Metro-Martinez allows it. The Marijuana onslaught is also looming.

On the horizon, Los Angeles is becoming dangerously inhospitable to any small business that is not cannabis. Growers are paying three times the asking rental price to set up indoor pot farms for their noxious and numbing substance. There may come a time when the only industry left in this city is marijuana.

The new refugees are small craftsmen running legitimate enterprises. Some may not believe it. But I heard it and saw it on Aetna, Bessemer, and Calvert Streets.

The pain is real, the fear is omnipresent and the situation is dire.

You must be logged in to post a comment.