Some six weeks ago, I went to MacLeod Ale and learned about an impending “slum clearance” in Van Nuys.

I was shown a sheet of paper in the owners’ office, laying out the destruction of the industrial neighborhood, just to the south of the brewery.

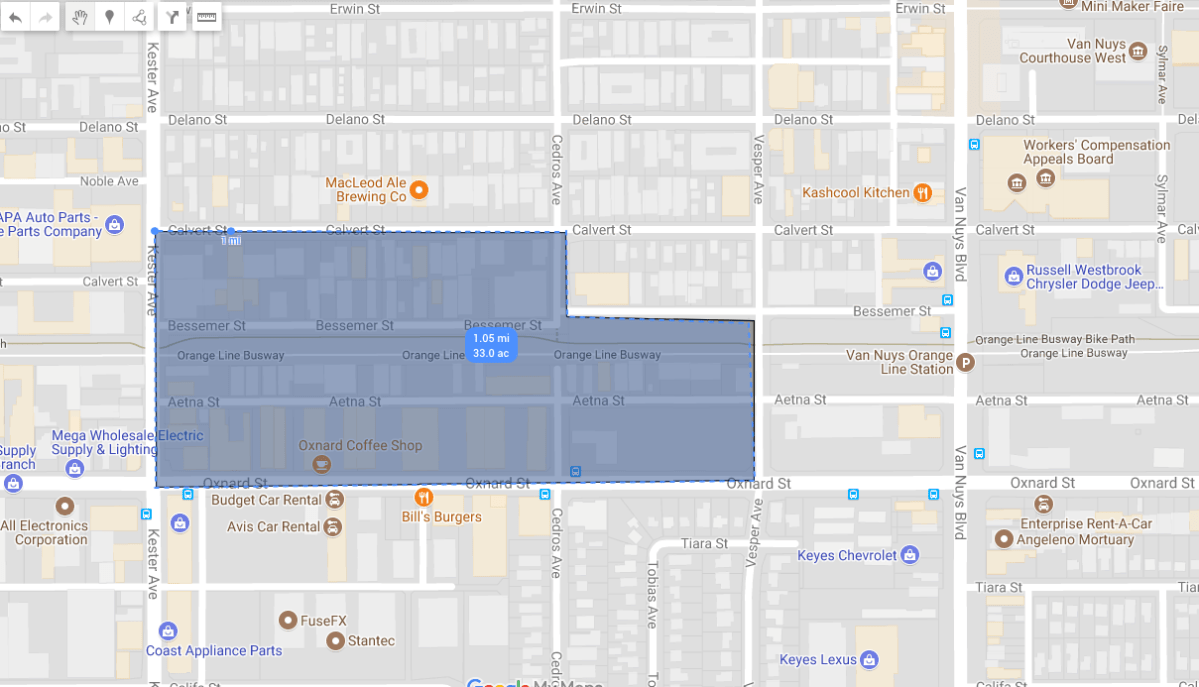

“Option A”, by Metro, planned to demolish 33 acres, stretching from the north side of Oxnard to the south side of Calvert, a hunk of real estate containing 186 businesses, 58 buildings, and 1,000 jobs.

A light rail maintenance yard would cover the area.

I had no idea what that meant, in terms of people and their livelihoods. I didn’t know anyone who worked there.

In my narrowly focused mind, MacLeod was, happily, not on the death list.

So I went back to my Better Days beer and forgot about Option A.

That First Email

A few weeks later, I opened a jabbing email from a stranger named Ivan Gomez.

He said he owned a business called Pashupatina on Aetna near Kester. “You seem to walk around our industrial community constantly looking for the worst possible things,” he wrote, possibly referring to a recent satire I wrote denigrating a certain low self-esteem street.

He said he was not wealthy, but “maybe you are.” He had plans to construct artist lofts. And he had just bought and renovated a blighted building. He described his plight of betterment:

“Sure there are a lot of missed opportunities with certain slumlords that own properties in the area. Don’t judge a book [by its cover]. Perhaps you can tell the stories that our buildings cannot. You can look inside and see we are all Van Nuys. We want to see change and if you are patient the change will come soon. If you are wealthy and can afford the price of admission than you will jump aboard the light rail gravy train. I proposed an alternate site that would save our manufacturing communities but that dream hit a bump in the road today. I urge you to reach out and help us tell our story. Hell, you might be able to make a difference,” he wrote.

He said he was slated for demolition and was fighting to keep his property and his district intact, to save jobs, and businesses, and dreams.

“I invite you into my facility to meet with a few of the people on Aetna, Bessemer and Calvert Streets who are trying to make a difference with the little resources we have to keep our area clean and safe.”

He said he had avoided the darkest aspects of life from gang violence to police brutality.

“I am Barrio Van Nuys, Pacoima Flats, San Fernando, Echo Park, Silver Lake, Angelino Heights, Lake Balboa,” he said.

His combative but challenging email intrigued me. I made an appointment to meet him, tour his place and the surrounding area.

Crossing Oxnard, North of Kester

Driving on Kester, near Oxnard, some of what one passes include day laborers on the sidewalk; the open sand and gravel yard of Valley Builders Supply; an al fresco used tire shop, Hamati Enterprises; Pat’s Liquors (check cashing, cold beer) asphalt parking lot and tall, ungainly, steel-posted plastic sign. And a big, looming billboard above it all; there is the shabby, tan painted, stucco entombed Uncle Studios, and Euro Motors’ turquoise doors and Virgin Mary mural.

In this blighted area, settled by the old Southern Pacific tracks, now the Orange Line, pickup trucks carry lumber, pipes, and sheets of glass. Sombrero hatted adults ride children’s bikes, others push shopping carts with belongings, addicts sleep and stare into space, buy cans of beer, and others reside in groups beside the bike trail. There are parked taco trucks serving lunch and many signs for auto repair, collision, bodywork, and smog certification. You are either working hard or hard up.

Hidden from view are many artisans, craftsmen, and skilled persons, working in fields from cabinet making to stained glass, from vintage auto and bike restorations to custom metal work. There are welders, boat mechanics, sauna installers, and music recording studios. Most rent fairly priced industrial spaces.

A sinister idea, it seems, would be trying to revitalize Van Nuys with light rail by wiping out this cloistered, unique, walkable, diverse, and industrious area.

Switzerland on Aetna St.

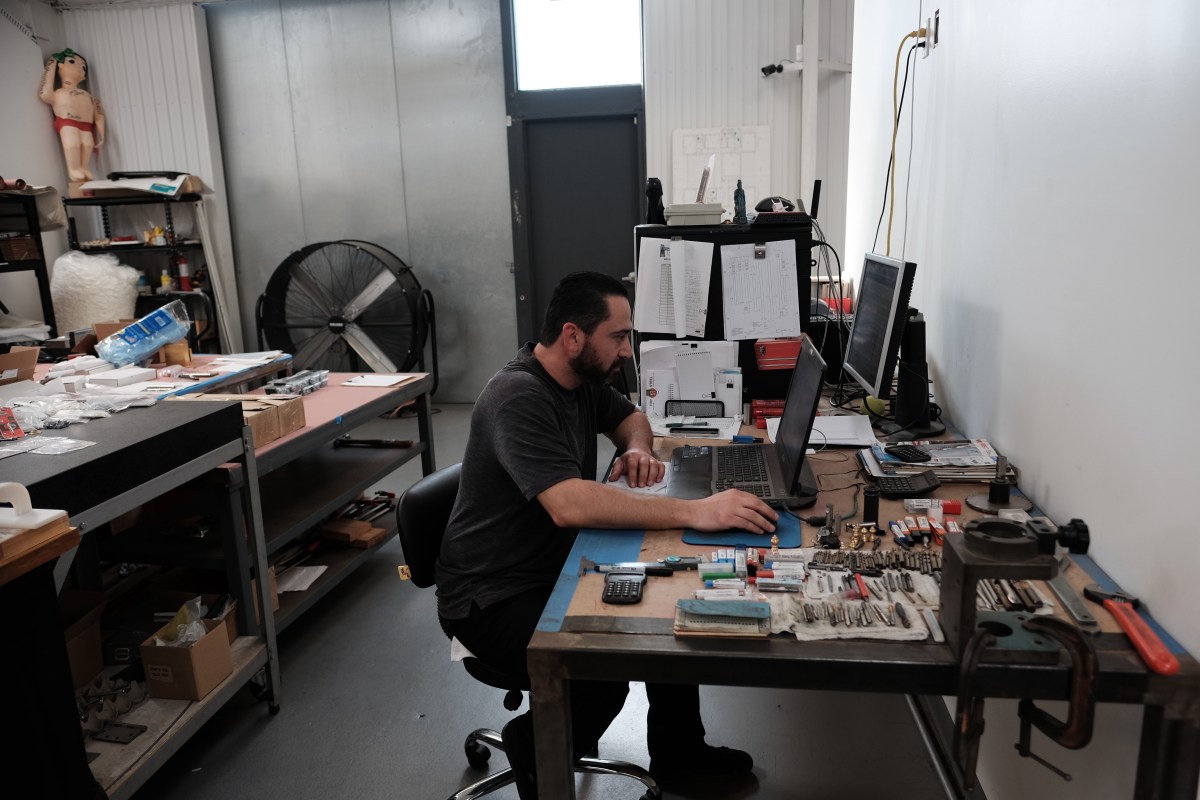

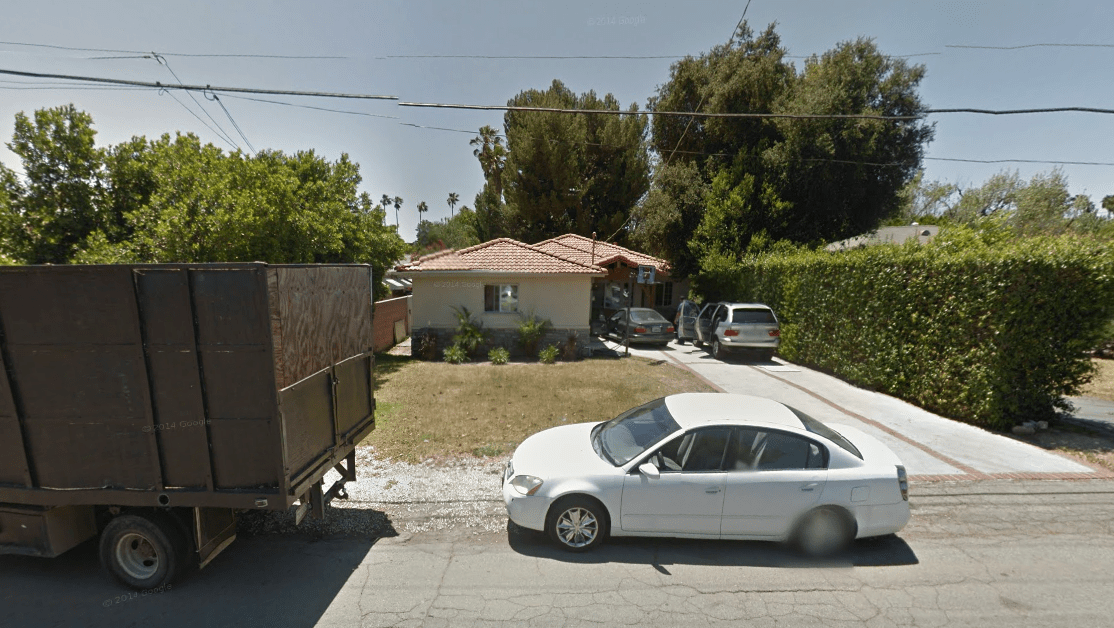

Pashupatina, at 14829 Aetna St. is an unmarked, pitched roof, building painted in cool shades of green and gray. A steel door is in front. But the preferred entrance is around the side.

You walk up a narrow driveway, paved in white gravel and concrete, squeezing between two cars, and enter a facility whose orderly, airy, bright, industrious and technically equipped rooms evoke some expert machine shop in a Swiss mountain village.

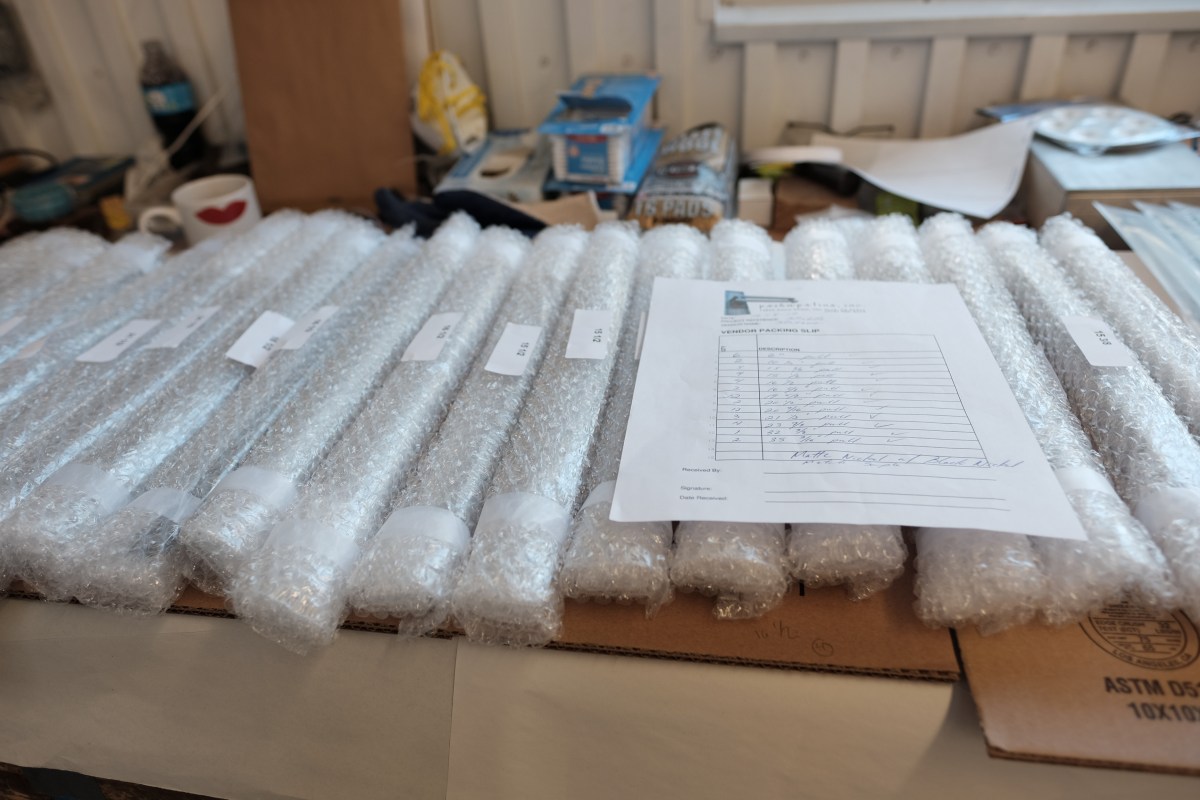

They are a manufacturer of custom decorative hardware, whose brass and bronze knobs, hinges, handles and levers hang inside some of the most expensive homes in Los Angeles. Boxes of surplus custom work, from recent projects, sit in the storage room on shelves labeled with Bel Air streets: Stradella, Casiano, Chalon.

Established 1997, the shop name comes from a most sacred Hindu temple in Nepal, Pashupatinath, dedicated to the god Shiva. Believers go there to die and be reborn in a holy place.

To a young Mexican-American, raised in Van Nuys during its most violent and convulsive years, escaping its lethal menace by sheer persistence, this name, this creation, must have multi-layered meaning.

Laid out on the floor, in orderly procession, on glazed concrete, are an array of metal lathe machines, electronically programmed, finely calibrated devices that drill to exacting standards for clients who are able to pay $1,000 for a single, museum worthy door knob.

There is a $50,000 Alaris 3D printer capable of processing CAD images and carving them into polymer models. This is where you will often find Ivan, at his computer, turning out those highly detailed or modern sculptural pieces that will be used as templates for custom metal hardware.

Pinned by magnets to the steel walls are enlarged architectural blueprints with the location of each piece of hardware designed, manufactured and installed by Pashupatina. The size, the detail, the scope seems on the scale of a museum or medical facility. But these pieces will go inside 40,000 square foot homes and 15,000 square foot guest houses.

Remember what you thought the Option A area was and then step inside here to be disabused of your ignorance. Think of all the princes, all the captains of industry, all the movie moguls, rappers, tech billionaires and their third wives who could not open a drawer or close any one of their 30 bathroom doors without Pashupatina.

Ivan Gomez, 45, his architect wife Natalie Magarian, 45, and his brothers Daniel, 42 and Manuel, Jr., 48 are all here, working.

Natalie and Ivan live in Lake Balboa, and Daniel and Manuel commute from Van Nuys and Canoga Park.

“Daniel and I are inseparable,” Ivan said. There is an affinity and closeness between them.

Daniel is thin, bearded, cheerfully fidgety with a rock-solid work ethic. He and Ivan rebuilt Daniel’s 1971 Corvette Stingray. It sits under canvas cover on a steel, 4-post lift just below Ivan’s 1971 Buick LeSabre, two cars, like two brothers in a bunk bed. A 1969 Plymouth Roadrunner, also owned and restored by Ivan, sleeps somewhere else.

“Daniel doesn’t put up with shit,” Ivan told me. The no-bullshit brother also owns a 40-acre home up in the desert near Palmdale where he can blow off steam and have fun. In 1994-95, to get away from LA for a while, Daniel and Ivan rented a home in Llano, CA. If they are ever at each other’s throats I imagine it’s one gently holding a razor and the other getting a hot lather shave.

The brothers (and Natalie) were renting another space nearby when Ivan saw a $500,000 building with 4,000 SF for sale. It was in poor condition, but they put in an offer. It was accepted and they got to work.

The entire structure, from the floor to the rafters, from the plumbing to the industrial grade electrical system, from the roof to the walls, to the driveway outside, the design, execution and construction, every last bit of it, was undertaken and completed by Ivan, Daniel, Natalie and other capable family and friends.

All their business comes from referrals. They don’t really have an online presence because they are too busy working.

They plan to one day have a retail line of their own, just like PE Guerin, a Manhattan company maker of exclusive, by appointment only, custom hardware.

Registering with the INS.

Ivan was born, by chance, in Mexico, when his parents were back there visiting. His siblings, Manuel, Jr., Cynthia, Daniel and Angel are all American born.

As a child legal alien, and then as an adult, Ivan had to register with the INS every few years. He became a US citizen in 2002.

In 1980, the family moved from Pacoima, where gang warfare had made life intolerable. They settled on Friar St. near downtown Van Nuys, at a time when the last white, Irish, working-class families still lived there.

Ivan was intelligent, curious, and industrious. He would buy popsicles from La Paletería, and resell them to his schoolmates.

He found employment with his neighbors: Tim Monaghan and his janitorial company, and with Richard Taylor who made miniature wooden piers for collectors that he constructed in his garage. Later on, Richard Taylor would hire Ivan to work in his custom hardware shop in West Adams. Ivan would become a professional locksmith, but unofficially, he was earning his masters in metal work in the four years he spent there. “Richard was a Shaman,” Ivan said in praise.

Ivan also worked as a boy janitor in an Oxnard St building a few hundred feet from Pashupatina. Always finding a way…..

Manuel Gomez, Sr. Ivan’s reserved, hard-working father, drove a Cadillac and worked as a punch presser at Zero Corporation in Burbank where they made metal stamped suitcases for the military. After Zero closed, Manuel worked at Just Dashes, a custom shop in Van Nuys.

Teenage Ivan also had a job at Bargain Books in Van Nuys where he was paid $2 an hour along with some used books. An autodidact, he often read up on mechanics or design.

The children were baptized Catholics, but their freethinking parents never pushed their children into any dogma or practice. By chance, the family joined the Salvation Army which treated the kids to summer camp and provided a social and support network.

Wilbur Avenue Elementary School, Tarzana.

Ivan was enrolled for two years at Wilbur Avenue Elementary School in Tarzana.

He met south of Ventura Boulevard kids, many of whom came from affluent, white families. They listened to Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin.

It was the mid 1980s and by that time Van Nuys was hit with a large increase in immigration, followed by plant closings (GM-1991), gang wars, drive-by-shootings, drugs, and the fleeing of white families from the disorder they saw all around them.

“I knew we were poor,” Ivan told me. He remembered having a rock thrown at him when he was three years old. He was shot at six or seven times before he was 25. One time he played dead in Panorama City and fooled his gun-wielding assailants.

He was Mexican-American, a target of cops who presumed guilt by ethnicity. He talked back to law enforcement when he thought they were wrong. He was handcuffed and targeted. He saw people in his neighborhood die from gangs, suicide, and shootings. He walked away from drugs and said he was a straight-arrow punk. As random acts of violence exploded all around him, he inoculated himself by diving into work, education, and music.

One day, at Van Nuys High School, a petite girl with a punky-pink haircut walked by Ivan and his friend. “Do you know her?” Ivan asked. “Yes, I do,” his friend said. He decided to write the girl a letter.

She was Natalie Magarian, born and raised in Lebanon. She came from a well-educated, well-to-do, Armenian family who left a war-torn land to live with relatives in Van Nuys. She spoke Armenian, Arabic, French, and English. She was interested in architecture and music. But she was odd-looking too.

“People said I dressed like I just got off the boat,” Natalie recalls.

Though Ivan claims to have seen her first, Natalie said, “Ivan liked me less than I liked him.” They came from wildly different backgrounds. Their respective families were kept in the dark about their relationship. “I think my parents wanted me to meet a nice Armenian boy,” Natalie said.

After graduating high school in 1990, Natalie went to study architecture at Woodbury University.

Also in 1990, Ivan went to work in a custom metal hardware factory owned by his Van Nuys neighbor Richard Taylor. The Jefferson Park Collection in West Adams is where Ivan would learn the craft that he would eventually master, emulate and reinvent into his own business.

Natalie and Ivan got married at the Transamerica Building in downtown Los Angeles in 1998. Architectural and secular and completely Angeleno, just like the couple.

They later found time to travel and explore Mexico, Cambodia, Singapore, Czech Republic, Portugal, Thailand. They lived in Silver Lake and Echo Park.

Years later they would come back to here in Van Nuys. And Lake Balboa.

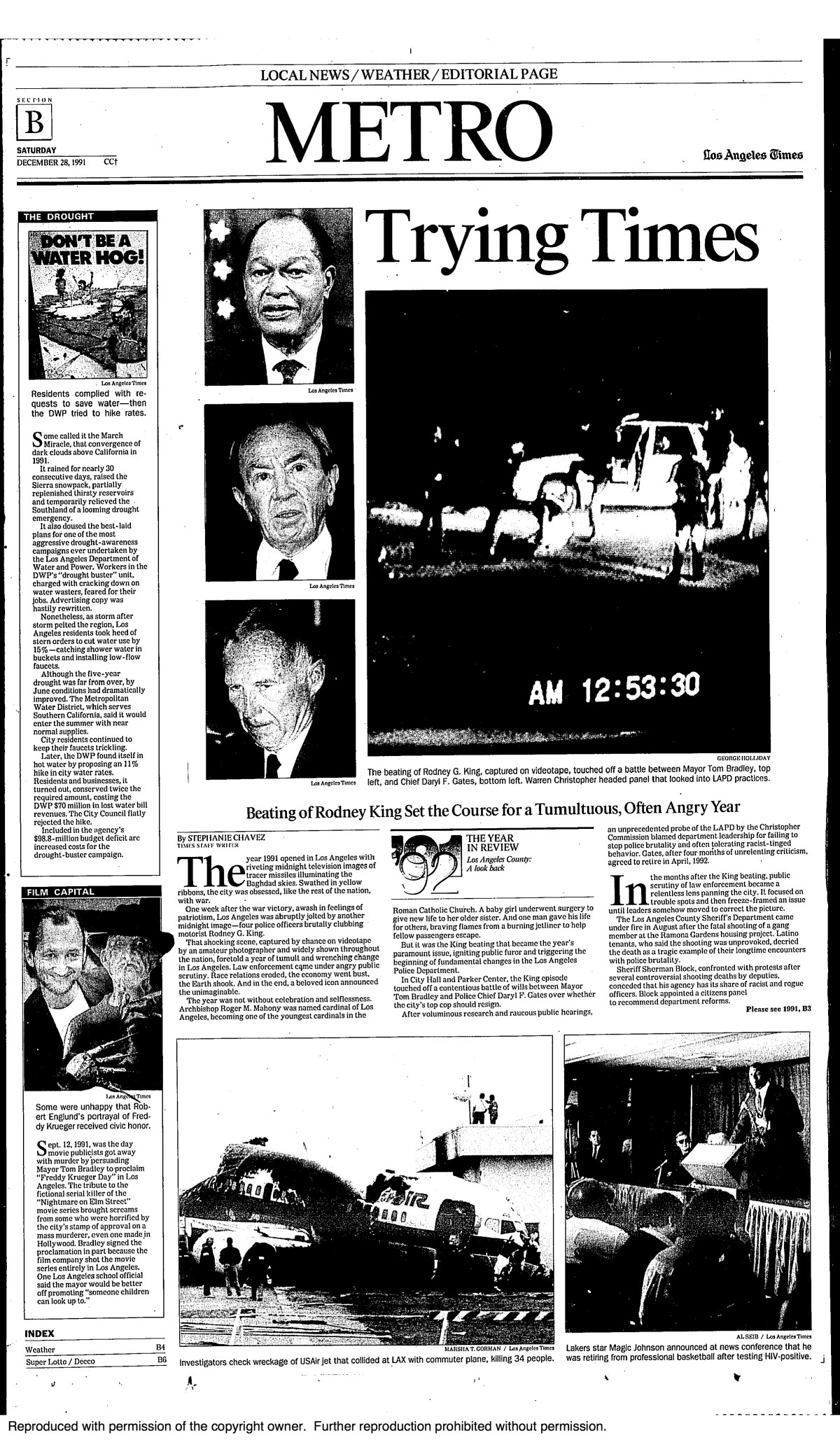

1991/1992

Rodney King was a black motorist beaten by four LAPD cops after a high-speed chase on March 3, 1991. A video, shot by a witness, George Holliday, captured the whole bloody event.

In that era, before smart phones, video recording of crimes was rare. The effect of seeing this brutality in action infuriated many who saw it as racism in action. Others thought the police were justified, and that toughness was the only way to stop crime.

The acquittal of the four white officers by a Simi Valley jury on April 29, 1992 lead to the worst rioting in Los Angeles ever seen.

“The riots, beginning the day the verdicts were announced, peaked in intensity over the next two days. A dusk-to-dawn curfew and deployment of the California Army National Guard eventually controlled the situation.[32]

A total of 64 people died during the riots, including eight who were killed by police officers and two who were killed by guardsmen.[33] As many as 2,383 people were reported injured.[34] Estimates of the material losses vary between about $800 million and $1 billion.[35] Approximately 3,600 fires were set, destroying 1,100 buildings, with fire calls coming once every minute at some points. Widespread looting also occurred. Stores owned by Koreansand other Asian ethnicities were widely targeted.[36]

Many of the disturbances were concentrated in South Central Los Angeles, which was primarily composed of African-American and Hispanic residents. Less than half of all the riot arrests and a third of those killed during the violence were Hispanic.[37][38]”

Images from that time include Korean shop owners on Western and Vermont Avenues wielding guns atop their roofs, and helicopter vantage footage of a white driver, Reginald Denny, being dragged from his truck and hit on the head with a brick, his skull cracking 91 times, beaten by a mob of youths.

The early 90s were an explosively violent time in Los Angeles. This was the era of the drive-by-shooting. A terrified city saw random killings spread into formerly safe areas, such as Chatsworth, Sherman Oaks and Westwood.

Once a refuge from urban crime, the SFV, had, by 1991, become plagued with it. Robberies increased to 6,638 up 40% from the year before. There were 142 homicides, a record.[1] Bad place names like Sepulveda, Canoga Park, North Hollywood and Van Nuys gave birth to North Hills, West Hills, Valley Village and Lake Balboa. Change the label and you will escape the consequences, or so the thinking went.

Flare-ups of sudden violence became normal.

On April 20, 1993, a disgruntled MCA employee, standing in a parking lot, used a Remington 700 hunting and target shooting rifle aimed at the Black Tower in Universal City. Seven employees were wounded by a 35-40 bullet barrage that shattered glass, caused mayhem and injuries, none life threatening, yet completely terrifying.

In June 1994, OJ Simpson was accused of murdering his wife Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman. His Ford Bronco chase on the 405 has entered the pantheon of legend. He was later found not guilty, despite so much incriminating evidence, on October 3, 1995. The verdict was thought by many to be payback to the LAPD for its mistreatment of minorities in Los Angeles.

Uncaused by humans, but just as devastating to them, was the January 17, 1994 6.7 magnitude Northridge Quake which caused $49 billion in damage and killed dozens of Angelenos.

“Among the wreckage were some 90,000 destroyed or damaged homes, offices and public buildings, according to the state Office of Emergency Services, with 48,500 homes cut off from water and roughly 20,000 without gas. Some 125,000 residents were rendered temporarily homeless.

When the dust settled, 57 people had died — including 33 from fallen buildings. Of those, 16 were killed when the 164-unit Northridge Meadows apartments collapsed atop its downstairs parking garage.

The fatalities included Los Angeles Police Officer Clarence Wayne Dean, whose police motorcycle plunged 40 feet off a collapsed section of the Antelope Valley Freeway. The Highway 14/Interstate 5 interchange was later renamed in his honor.

More than 9,000 people were injured, including hundreds treated outside a topsy-turvy Northridge Hospital Medical Center. Twenty-one preemies from its neonatal ICU were airlifted to other hospitals.”[2]

Ivan In the Time of Turmoil

“The best thing that happened to us was the underground dance music scene from 1989-93. It allowed us to get away from the Valley into safer places. We met a lot of cool people and spent time up in the Hollywood Hills,” Ivan told me.

While the city and his neighborhood, were racked by violence, Ivan took refuge in the music world, and in his work.

He was up in Sylmar one Sunday, skateboarding in the wash, when he met a guy Rey Oropeza who had a hardcore, rap political band called Social Justice (later Downset) who in turn introduced Ivan to hundreds of different writers and artists from all different walks of life.

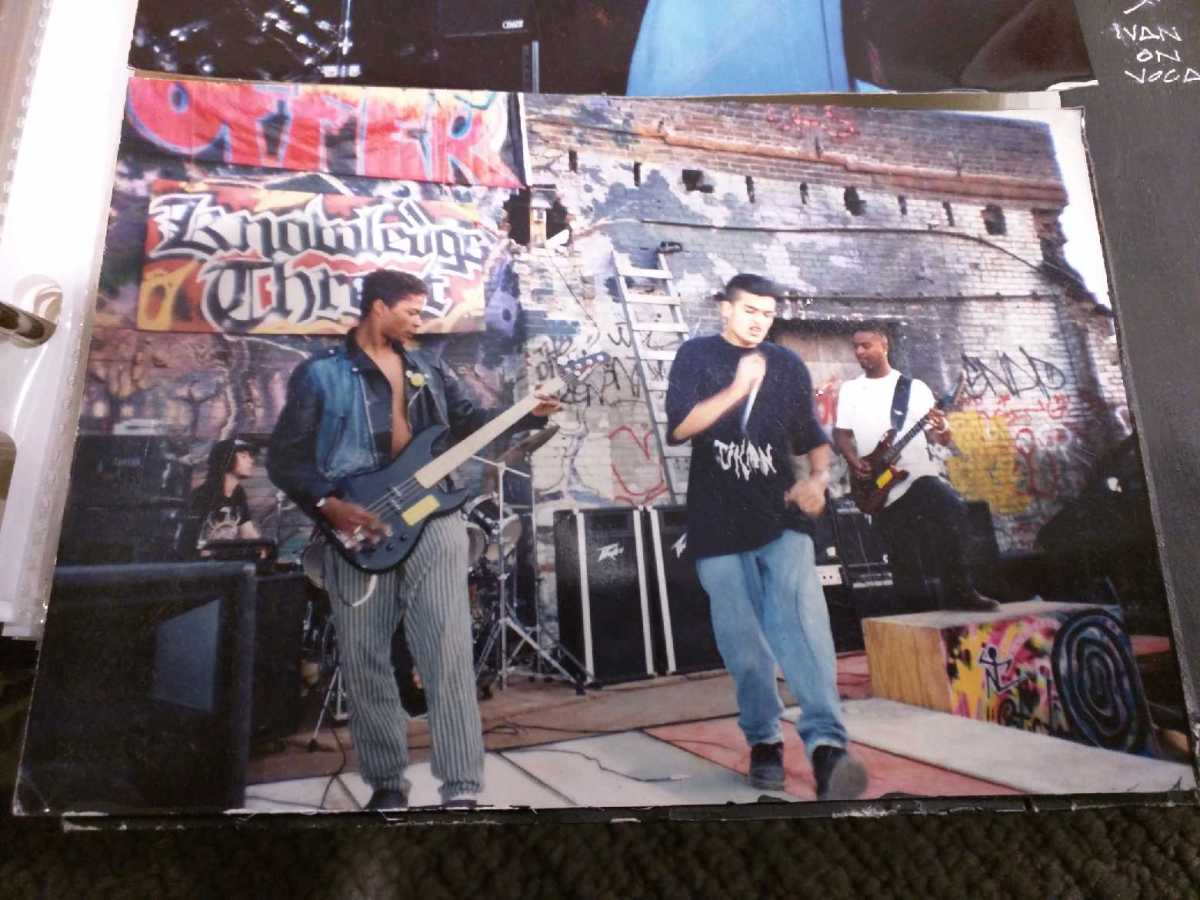

Ivan was working at Aahs and so was Darren Austin and Cameron. They had an idea to start a band so Stikman was born, an idea that Ivan came up with. He was the vocalist, Cameron, a white dude, drummer and Michael Glover, a black kid, played bass. And Darren, another black guy, was a guitarist.

Ray, Darren and Michael were all graffiti artists part of a crew known as Under the Influence (UTI).

In the parlance of that time these were a “mixed race” group of musicians. Music, and people, at that time had more fixed boundaries of race, and culture, and human beings in Los Angeles also often self-categorized themselves into racial classifications, immutable and ridiculously rigid. But Ivan and his friends were in the vanguard of the new mashup city we live in today.

A photo of five of them, circa 1990, shows young Ivan, smooth-faced, hair band around his forehead, dressed in a black, boat necked shirt, holding what looks like sheet music, a large necklace around his neck.

He is, in that photo, modern but timeless.

His flat nose, his jewelry, his stance, his gentle, warrior aura beating tribal, evokes pueblos indígenas de México. He stares insightfully at the camera, as if he directed fate and not the reverse.

Stikman, Ivan recalled, sounded like Nirvana, which someone once told him, “stole your sound.”

The band was young, exotic, and got a following. They were adventurous, driving after dark to dangerous places along the orange, mercury lit streets. They would break into empty warehouses, guerilla style, near downtown, setting up impromptu concerts and raves.

After high school (1990), Ivan Gomez also had jobs in retail. He worked at Tower Records and Aahs a novelty store, both on Ventura Bl. in Sherman Oaks, west of Van Nuys Bl.

Some of his musical influences were AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Iron Maiden, Cure, Echo and the Bunnymen, and The Sugarhill Gang, a late 1970s hip-hop group.

Stikman’s great moment of glory: they played Raleigh Studios in 1993 in front of 3,000. They had arrived in Hollywood and got inside the gates.

They were together and making music. And then they were not. The band broke up in 1993.

Later Michael committed suicide.

Ivan and his friends were getting off work at Aahs around 10pm one evening in 1993. They ran into some homies from BVN in the alley behind the store. The gangsters were delighted to see Ivan and happily showed him a trunk full of weapons. Ivan thought it was time to say good night. As the gang car with guns drove off, another car, full of a white gang, started shooting at Ivan and his friends and yelled “Gumbies 13!” Ivan and friends ran for cover and could see BVN speed after Gumbies 13. The white gang, from Ivan’s recollection, crashed and BVN “took care of them.”

Then LAPD arrived in the alley to interrogate Ivan and his friends. They were lined up and interrogated. They were pretty ruthless and one pointed a gun at Ivan’s head, he recalls.

To those too young to remember, violence was unrecorded by smart phones before 2007. Cops and criminals, and criminal cops could do pretty much anything they wanted to without being filmed.

Like religion today, you either believed the tales told from the pulpit of police record or you didn’t.

Atelier Pashupatina

Pashupatina employs eight highly skilled men and women who work together to execute designs in a shop where there are deadlines, machines, stress, and sometimes arguments and conflict. But the environment is soothing, cerebral, edifying, more like an atelier, an artist’s studio, than a factory.

The layout is architectural, drawn up by Natalie. She had worked in Frank Gehry’s firm. She still has other international and domestic gigs. Her influence in creating an architectural stage set is not accidental, and comparisons to lofty, elitist creative spaces in Culver City and Venice are warranted.

Pashupatina does not have furnaces. The caustic, burning, smokey parts of the metal making process are sent out. The dirtier and harsher and more primal parts of casting, blasting, and plating are outsourced. But machining, and drilling are done here, and buckets of bronze and brass scrap metal, grindings, collect in big quantities and are sold to recycling.

Should I Be Doing More?

“Technology is not an image of the world but a way of operating on reality. The nihilism of technology lies not only in the fact that it is the most perfect expression of the will to power … but also in the fact that it lacks meaning.”

Octavio Paz (1914-98), Mexican poet. “The Channel and the Signs,” Alternating Current (1967)

President Obama once described America as the one indispensable nation in the world. Ivan, in his family and work, seems to share that characteristic, as a man, that Obama subscribed to the USA.

“Everyone puts the burden on me,” he said.

Ivan spoke as a married man, with two small children and a thriving, technically advanced company, with many responsibilities, worries and duties.

And yet he ponders if he should be doing more.

He was thinking, perhaps, of our ruthless, opportune, robotic time.

He was acknowledging that the wealthiest people, his clients, hoard money and power, leaving a gap, enormous and hollow, in this nation, this state and this city.

Here was this “job creator”, this self-made person, embodying all the hoary clichés of America: the idea that if you have the will, the guts, the ambition you can do anything.

But he is also the Mexican, the immigrant, the other, who was once despised, feared, and whose people still battle, daily, to convince this nation that they are just as American as other Americans.

Ivan, like all of us who live here now, sees the suffering.

For the community of Van Nuys

For the people who are still struggling

For the ones who are roaming the streets

For the people who are poor, neglected, or lost

For the addicted, the suicidal, the abused, the unemployed

For the undocumented, the deported, the incarcerated, and the damned

You are overlooked but you will not be forgotten

There will come a day again of brightness, hope and redemption

Here is a man who has used technology to advance his life and create paid work for which he is proud. But he is still asking: what does it all mean?

It is a valid question that a particular type of moral thinker will ask.

Is there anything greater to give back?

Kesterville: Seen and Heard

Last week I learned a new word:

Enjambment

The running on of the thought from one line, couplet, or stanza to the next without a syntactical break.

It came, courtesy of Dictionary.com, in their daily email and the arrival was fortuitous because I grabbed that word and pinned it on Ivan Gomez.

He is ebullient, gushing, buoyant, effusive, often pouring out with a million ideas and directions at once. His first email to me was a screed of run-on-sentences, accusations, pleas, suggestions, offerings, come-ons and inventions of both reality and fantasy.

He will dream it and do it and make it and sell it and seek it and reinvent it.

Meeting Ivan and the people who work in Van Nuys, the metal workers, the wood workers, the stained glass maker, the Vespa restorer, the musicians, the boat yard mechanics, all the hard workers who wear grease stained aprons, breathing dust, inhaling paint fumes, crawling under machines to screw in parts, all of them made me both proud and ashamed.

I was ashamed, indulging in self-pity and living inside my imagination, while others were working and sweating in shops making real things, utilizing skills and tools and machines I had never operated, or learned or knew anything about.

What did I have but words and photos and opinions and artistic license?

When I joined up to fight for the folks on Option A’s Death Row I had no idea how much life existed in Van Nuys inside the metal walled shops, behind the garage doors, down the streets where the sound of the bus roared nearby, under the unmarked, steel roofed packing houses.

I thought I was educated but I was so dumb.

I was lassoed out of my solipsism.

I like to think I did something good in Van Nuys to preserve something meaningful. It all started with that first email from Ivan.

In January 2018, Metro will make an official announcement about where the new light rail service yard will go. Councilwoman Nury Martinez now opposes Option A and others were told, unofficially, that other powerful people now agree that Option A is a bad idea whose time has come and gone.

Options B, C and D are all located near the Metrolink train tracks not far from Van Nuys Boulevard. They would not be nearly as destructive as Option A.

# # #

[1] 1991: A Look Back: Review: The Rodney G. King beating, development … HENRY CHU TIMES STAFF WRITER Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File); Dec 30, 1991;

[2] http://www.dailynews.com/2014/01/11/northridge-earthquake-1994-quake-still-fresh-in-los-angeles-minds-after-20-years/

You must be logged in to post a comment.