The other day, I drove past the gray ranch with white casement windows at 4336 Teesdale, a house I briefly lived in for 4 months when I arrived in Studio City in May 1994. There was a for sale sign in front, so I stopped my car, got out and started to take photos for posterity.

A middle-aged Israeli, parked nearby, emerged from his SUV to ask me why I was taking photos of “his house.” I told him I had lived there many years ago. “I am on the neighborhood watch,” he said.

I explained that I knew the previous occupant and had lived here myself. I asked him how much the house sold for, but he would not say. He said he was a broker, but “I don’t like to call myself a broker. I’m more of a preservationist.”

He told me the house, most likely, would be torn down.

He seemed satisfied with my benign answers and he drove away.

Redfin, I saw later, listed it for $1,034,500.

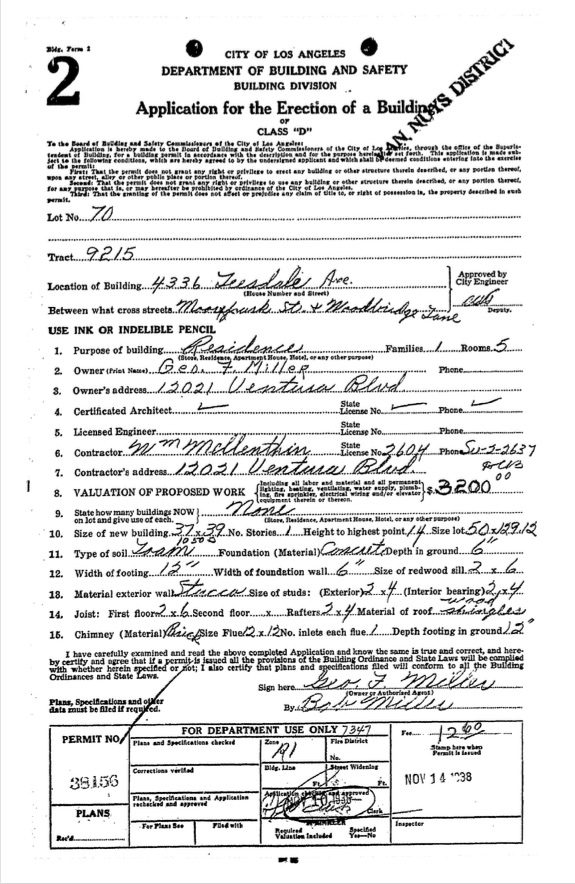

In 1994, a college friend, “B”, was renting it for $1,200 a month. There were two bedrooms and one bathroom, 1168 square feet, built in 1938 for $3,200. I paid “B” $100 a week when I earned $500 a week as a PA.

“B” went away for the summer to work on “Woodstock ‘94” a twenty-fifth anniversary program of the rock festival. I stayed in the house and got a job at Greystone in Valley Village where the hazy air obscured the view of the mountains and everyone went across the street to get lunch at Gelson’s salad bar.

When “B” returned we fought over something silly and we never spoke again. And I moved out.

Everyone sees their life and their times in their own way. And we interpret our communities with stereotypes we overlay on them. And Studio City has stayed in my head as a certain place, regardless of fact or reason. It still exists in my imagination in that way I first encountered it that summer in 1994.

In the 1990s, there was a family type who lived in Studio City, not at 4336 Teesdale, but in many other homes. I often met them on runs when I worked at Greystone.

The mom was always named Linda. She was single and raising two teenagers in a two-bedroom ranch that looked like 4336.

She was 43-years-old, with a perpetual tan, curly dark blonde hair, living in a tiny house with many VHS cassettes, tons of books, two cats (Cat and Kitty), a bedroom with burgundy sheets, a leopard print comforter, brown velvet pillows and a chenille throw. Her fireplace mantle was stacked with scented vanilla candles and ornate gold-framed photos of her two kids who were always named Zoe and Adam.

There were three closets in the home, each 23 inches wide, and the front hall was stuffed with everything nobody would ever need in Southern California: waterproof boots, winter coats, sweaters in dry cleaner bags, hats, gloves, mittens, a file cabinet and an Electrolux Steel Framed Canister Vacuum.

Linda was always a writer/producer and had worked on documentaries about Nostradamus, the Titanic and “The World’s Most Amazing Dogs.” Her new boyfriend was always a bearded therapist named Robert or Steven and he had a dry, calm, objective, scientific and analytical view of everything from genocide to dieting to menopause. He was always rational and grown-up, in contrast to the immature first husband. He never lost his temper unless someone disagreed with him.

He ended most arguments with this winning argument: “Chomsky said it. I believe it. That settles it!”

He knew wine and he knew women. And he had classifications and opinions on both which he pontificated upon with his index finger waving in the wind.

Linda drank highly oaked Kendall-Jackson Chardonnay and treated herself to Wolfgang Puck’s pizzas topped with smoked salmon and caviar. After coming home, stuffed and intoxicated, she plopped down into her overstuffed sofa which took up almost her entire 10 x 12 foot living room.

She was divorced, always from David, who always moved to the beach, and they had joint custody of the kids whom he picked up on Friday nights, two times a month, in his Jetta Convertible. David was always an editor. He had once worked with Scorcese, but had a falling out. He was said to be bitter, but he still earned $5,000 a week working for NBC or Universal and had a 25-year-old girlfriend, who was always tall and always named Jennifer.

The broken up families of Studio City, twenty years ago, were always white, and they were always from different white backgrounds: Jewish and Irish, Jewish and Italian, Jewish and Atheist. They were always self-professed liberals and had always grown up in completely segregated, wealthy neighborhoods and were uniformly horrified at the downfall of their former hero Orenthal James Simpson.

They always came from back east, and had attended Ivy League schools, some earning MBAs, always with the intention of using their top-level education to write or produce Hollywood sitcoms.

Someone’s parents had always lent them $23,000 for a down payment on a $239,000 house off of Moorpark near Whitsett. “Your father killed himself saving this money for you so you would have it for this very reason.”

The parents were always difficult, but always present, in daily phone calls. When the phone rang at 6am, the parents back east never knew it was three hours earlier in California. Every August they mailed a check for $3,000 to pay for Adam and Zoe’s yearly tuition at Harvard-Westlake.

Long gone, are the struggles of 1994, those days of worry when you wondered how you would pay your $657 a month mortgage. The women who stayed put in those houses are now gray or white haired though most are still outwardly blonde. They are all passive millionaires who live in million dollar homes.

So many have sold their little quaint houses with the rope swing tied on the tree in the front yard. The picket fence, the one car garage, the kitchen with two electrical outlets and no dishwasher, the pink bathtub with plastic non-slip flowers, the glassed in back porch, the one bathroom shared by four people: all wiped off the map in Studio City.

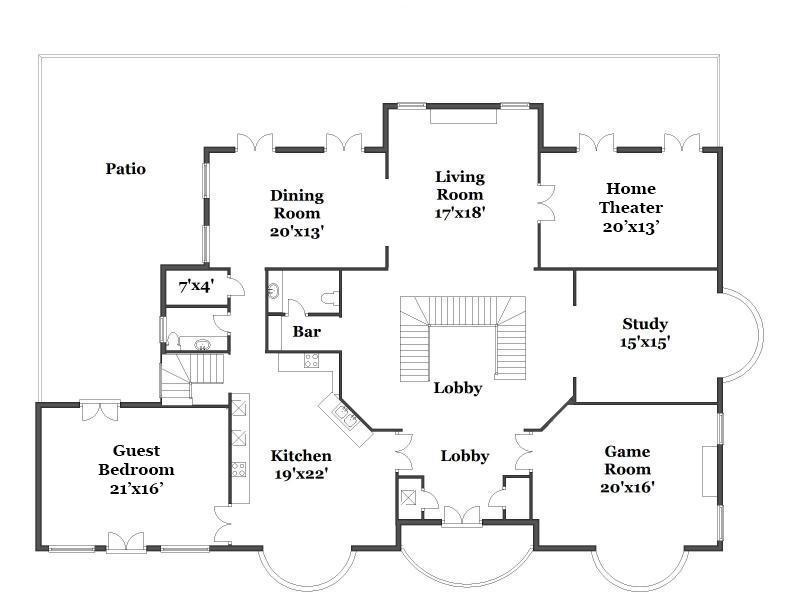

In 2017, the new house is always white, always “Cape Cod”, always 5,000 or more square feet, always “amazing” (is there any other word?) with five bedrooms, five bathrooms, 15-foot high ceilings, with high security systems and cameras affixed around the exterior to catch squirrels, possums, robbers and send alerts day and night. The 89 windows are never opened and the air conditioning is always on. There are 100 overhead lights in the combined living/dining/den/kitchen/wine bar/library/pool/patio.

The walls are always white and there are no books, not a single one, anywhere, except if they are on the coffee table, and then they are photography books, and they sit in front of the 86″ Class (85.6″ Diag.) 4K Ultra HD LED LCD TV: $6,999.

(Text continues after egregious photos)

There are always two SUVs parked in the driveway, usually a Mercedes and a Lexus. They have Bluetooth and Wi-fi but every woman who drives one uses her handheld phone to talk while accelerating through red lights driving Sophia and Aiden to school safely.

Nobody cooks in the kitchens with the 50-foot long counters and the 10 Burner, $16,000 Viking Range. They just get takeout from Chipotle.

Inside these vacuous homes, nobody reads and nobody converses. They just look at their phones. Everybody has a spine like a banana and red, callused, sore thumbs.

The old Studio City, cramped life creatively lived, is fast under demolition and in its place something alien, gargantuan, empty, expensive and all-white fills in the empty lots on every quaint street like a new set of false, horse-tooth-sized dentures rammed into a 4-year-old girl’s mouth.

The bulldozers, I expect, will come soon for 4336 Teesdale. The 80-year-old house will be a pile of wood by lunchtime. And then a new lot will get dug, the new foundation poured, and stacks of lumber, men and tools will put up a new spectacular that looks like every other new spectacular in Studio City.

And upon completion, the realtors will smile, the banks will lend, the in-laws will underwrite, and some young family will be in debt for $2,500,000 for the next 30 years, if they are lucky.

You must be logged in to post a comment.